South Korea is famed for its efforts against COVID-19; it quickly abated its spread and saved thousands of lives.

Only 289 of its 51 million inhabitants had died from the virus in early July since its first case in February – compared with 44,600 COVID-19-related deaths among the UK’s 66 million population.

So how did this east-Asian powerhouse – known for its hi-tech cities and high-street brands, such as LG and Samsung – and its doctors flatten the curve with such speed?

South Korea’s approach to COVID-19 was helped by its experience in 2015 of MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) – another coronavirus that claimed 38 lives, its doctors say.

We never had a lockdown. No business or hospitals got shutProf Park

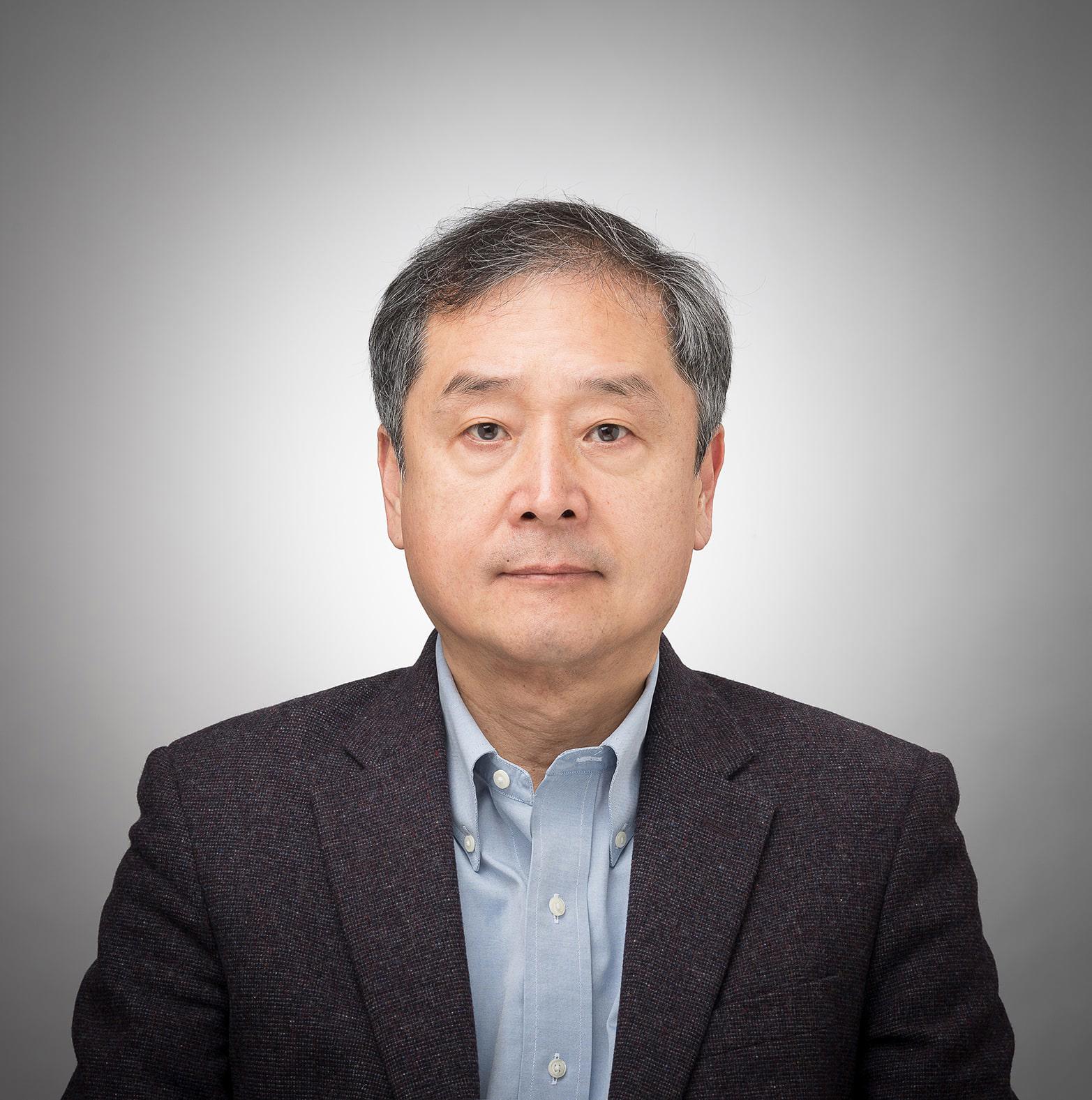

‘The way we dealt with MERS wasn’t satisfactory,’ says Ducksun Ahn, president of the Korean Institute of Medical Education and Evaluation and professor of plastic surgery at Korea University Medical College.

‘It was very embarrassing,’ Professor Ahn adds. ‘It created a great fear in society. With that fresh in their memories, people hearing of this new epidemic were anxious and so followed what the Government asked them to do.’

Experience counts

‘MERS helped humongously,’ agrees Hyunmi Park, a UK-trained colorectal consultant surgeon, now a visiting professor in robotic surgery at Korea University Hospital. ‘It’s helped in the track and trace but also in the regulations that were introduced for small and medium pharmaceutical companies to produce test kits very quickly,’ Prof Park adds. ‘As soon as we had a sample of the virus they were able overnight to start making test kits. We produce and even export as many as we need.’

This measure meant 120,000 tests could be carried out daily almost straight away, says Prof Park, as the UK struggled to hit its initial target of 10,000.

On the front line, patients with any symptoms are tested in pre-assessment areas, away from hospital front doors. Any booked for elective surgery – and their families – are tested too. Results return in hours.

We had maximum protection. But I’ve been feeling very guilty when messaging my friends in the UKProf Park

‘We didn’t cancel anything,’ says Prof Park. ‘We never had a lockdown. No business or hospitals got shut. The Korean people are also very obedient and very responsible towards their fellow humans,’ she adds. ‘It was described as a “big snowy day”, an extended one, obviously. On such days, Korean people just stay at home.’ While restaurants remained open, few had much business, she adds.

Social-distancing advice was issued by its Government to reduce meetings, travel and contacts and to encourage hygiene measures such as regular handwashing and the etiquette of coughing into sleeves with masks on.

Supply in swing

PARK: 'I never felt unsafe'

PARK: 'I never felt unsafe'

South Korea avoided the worldwide shortages of PPE (personal protective equipment) that hit the UK so hard, alarming and distressing its health and care staff.

Such was its supply, each citizen could buy two N95 masks weekly for the equivalent of £1. ‘Koreans demanded to have N95 masks and they got them,’ says Prof Park. ‘They were all wearing it. They still do. That’s the norm.’ They’re delivered to the door of anyone aged over 65. Healthcare staff had advanced respirators.

‘I never felt unsafe,’ says Prof Park. ‘We had maximum protection. But I’ve been feeling very guilty when messaging my friends in the UK. All I hear is, “we don’t have enough PPE”. That was really sad for me. I felt really bad.’

Prof Ahn says, ‘uncertainty and avoidance are one of the characteristics of Koreans’. ‘Whatever the evidence shows they want the best model, the guaranteed model,’ he adds. ‘In hospitals, high-level PPE is very cumbersome, particularly in this hot weather, but people preferred to have the more secure ones.’

App efficient

South Korea also made use of a track-and-trace system which filtered huge volumes of personal data from citizens’ cell phones, credit cards, and CCTV footage to pinpoint their movements. Anyone located near a new COVID case were flashed warnings on a disaster alert app which almost everyone has on their mobile phones.

‘It warns if typhoons are coming and now if you were in the vicinity of a positive patient,’ Prof Park says. ‘It will tell you where they’ve been, to which shop or hairdressers and at what time. You check if you were at the same place at the same time and go and get tested for free. At the beginning in March, everyone said that their phones were on fire.’

If we had a heavy number of cases, like the UK, we probably couldn’t handle it eitherProf Ahn

In some cases, people’s movements were publicised on TV and news sites, sparking debate and outrage at their actions. One man was reported to have gone to a restaurant, a sex hotel, another restaurant and on to another sex hotel in one night. Aside from comments on his stamina, such actions were criticised harshly online. ‘People are very ruthless here about people’s behaviour when it affects the whole community,’ Prof Park says.

State surveillance

AHN: 'The way we dealt with MERS wasn’t satisfactory'

AHN: 'The way we dealt with MERS wasn’t satisfactory'

Prof Ahn says doctors in South Korea are concerned about the right balance between access to personal information and the benefits of the track-and-trace system. ‘We were worried about a slippery slope towards some kind of totalitarian surveillance. We’ve been through a non-democratic regime for a long time and we don’t want that again.’

Prof Park has weighed the pros and cons of intrusion into her privacy against the UK’s experience with her ex-pat friends. ‘We are all agreeing that maybe a little bit of privacy intrusion and telling you what to do and what not to do might have been better than having 45,000 people die.’

If something happened in Seoul, could we manage here? We’re not quite sureProf Ahn

For all its measures, South Korea has suffered outbreaks, some requiring a national response. The largest so far was traced to a religious group, which Prof Park describes as a ‘cult’, in Daegu, a city with some 7,000 cases among its 2.5 million citizens. More than two-thirds of the country’s 280 COVID-related deaths are here.

Some 1,000 young doctors who were on public health duty for national service were mobilised to deal with this outbreak. Universities despatched respiratory specialists. Hundreds more doctors volunteered, says Prof Ahn. ‘They admitted every single patient to hospital,’ he adds. ‘That’s why the mortality rate was so small.’

Potential disaster

The Daegu outbreak and its draw on resources remains a concern for Korean doctors. A significant outbreak in the capital, Seoul – six times the size of Daegu – could test them further. Cases there still hover at just 100 a day.

‘If we had a heavy number of cases, like the UK, we probably couldn’t handle it either,’ says Prof Ahn. ‘We managed with a sudden surge and outbreak in one city; it was contained effectively,’ he adds. ‘The Korean Medical Association is very worried that many health professionals are already burned out. If something happened in Seoul, could we manage here? We’re not quite sure. That’s the challenge. We are still worried about it.’

Like all countries, there are also concerns about the economy. The industry which kept hi-tech supply chains of PPE and testing kits healthy has suffered, as export income fell.

And now, almost a month into summer, doctors fear people will feel less and less like COVID-19 is just another ‘big snowy day’. ‘It has started to get really hot and nice,’ says Prof Park. ‘During the wintertime, people don’t mind staying at home. They now want to go out and enjoy themselves. We’re worried about that.’