You have heard the one about doctors moving to Australia for better pay and conditions but a lesser-reported exodus is happening much closer to home.

There might be more kangaroos than four-leaf clovers on picket-line placards but what appears to be a growing number of doctors are moving from the UK to work in the Republic of Ireland.

Doctors who may want to remain closer to friends and family but who are equally fed up with NHS working conditions are being targeted by online adverts for jobs in Ireland, with reports of recruiters turning up at picket lines to offer information.

Ireland shares a common travel area with the UK, allowing citizens of both countries the right to live and work in the other. It is third on the list of destinations doctors gave to the GMC for where they intend to move to when leaving to practise abroad.

In the latest GMC Workforce Report, which uses 2022 data, 310 UK-based doctors say they intend to move to Ireland – 26 of whom were British, 129 Irish (those born in Northern Ireland could say either) and 155 of other nationalities. But this data does not confirm their intended move came to fruition – and many doctors also keep their GMC licences to practise after moving from the UK to keep their options open.

Numbers unclear

IMC (Irish Medical Council) data is also unclear, as it measures where doctors went to medical school rather than where they were previously working.

Of the 3,008 doctors who registered with the IMC for the first time in 2022, 56 studied in the UK, 867 in Ireland and 465 elsewhere in the EU. More than half (1,620) went to medical school in neither the UK, Ireland or the EU.

All categories could include doctors who were working in the NHS before registering with the IMC, which told The Doctor: ‘We do not know how many doctors came from the NHS to Ireland.’

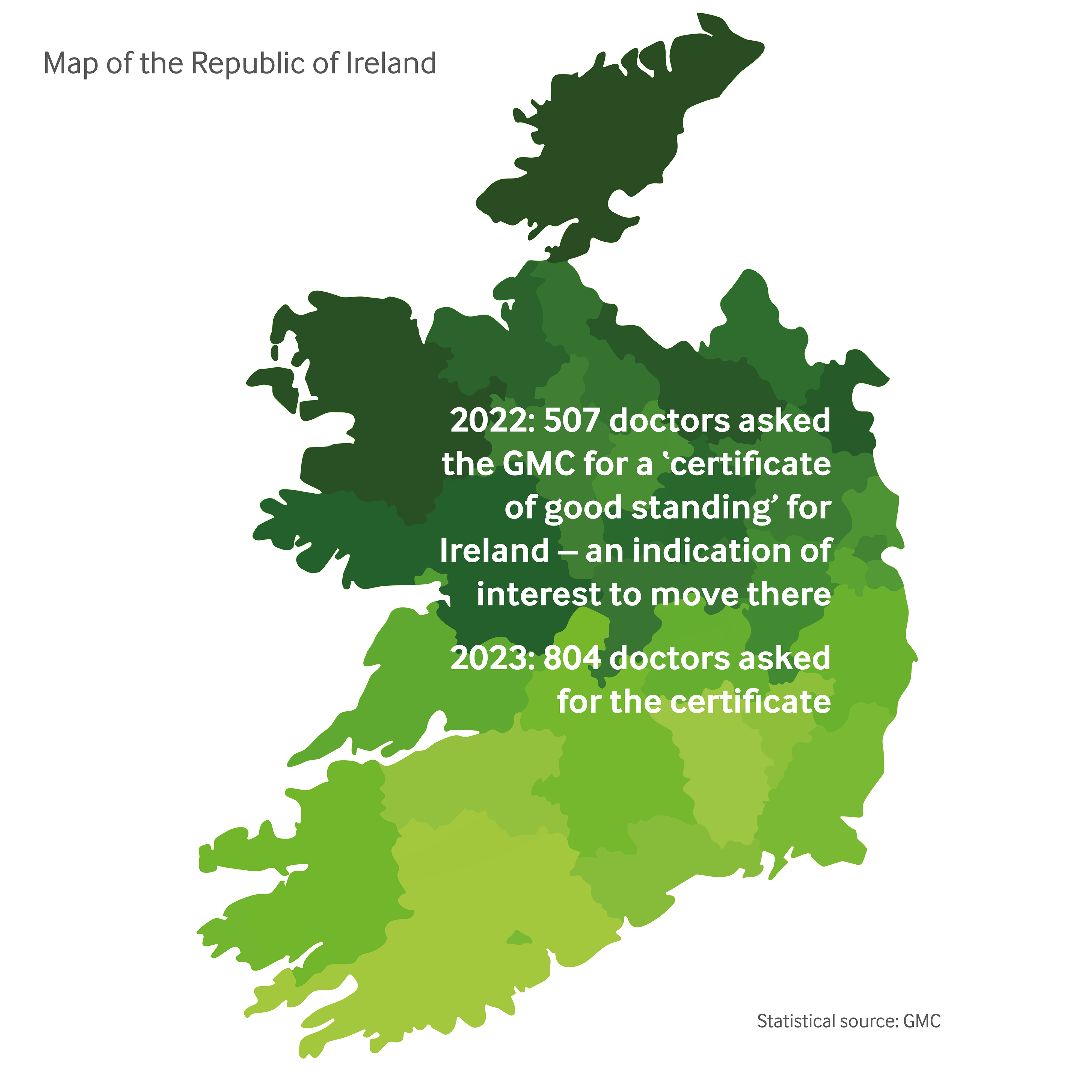

Separate GMC data unearthed by The Doctor perhaps gives the best indication. Some 507 UK-based doctors requested a CGS (certificate of good standing) for Ireland in 2022, with 334 retaining their licence to practise.

In 2023, 804 doctors requested a CGS for Ireland, with 632 retaining their UK licences, as of late January. Requesting a CGS is not proof that a doctor has moved, but shows they are taking active steps to do so.

Respect and remuneration

Kathy Gallagher (pictured above), a paediatric rheumatology consultant, and her GP husband Tom Mathias moved from London to Dublin in September 2022.

Dr Gallagher originally hails from Donegal on Ireland’s Atlantic coast but worked in Nottingham, the east of England and London’s Great Ormond Street Hospital after studying in Norwich.

While working in the UK was ‘a great experience’, she says it ‘wasn’t easy’, including 12 house moves in 16 years for rotations and university.

Dr Gallagher was offered a position a year in advance, meaning she could finish her specialty training in London and plan the transition.

‘Respect’ is a word many UK-based doctors use when complaining about pay and conditions in the NHS, and Dr Gallagher says being offered respect in Ireland is a big reason why the 10 Irish students she trained with are ‘slowly filtering back’.

I come home from work and I’m not tiredDr Mathias

She says junior doctors she has worked with in Ireland report similar such respect in relation to their working conditions and pay, particularly in terms of exception reporting and study budgets.

With many junior doctors keen to complete their specialty training programmes before moving, a big sell for recruiters to Ireland’s health service is its new Sláintecare consultant contract.

It offers up to €252,150 (around £215,000) for a 37-hour public sector week, extra pay for on-calls and overtime, protected time for research and teaching plus the freedom to take on private work provided public obligations are met.

Dr Gallagher’s consultant role is still ‘very busy’, and waiting lists long, but she says the set-up creates a ‘camaraderie’ and ensures patients who need urgent care are seen in time.

And while IT systems can be just as frustrating as in the NHS, she is confident a recent investment announcement will improve things.

MATHIAS: Able to work ‘more proactively’ as a GP

MATHIAS: Able to work ‘more proactively’ as a GP

Moving meant Dr Gallagher left behind her ‘professional support network’ and many colleagues she had grown close to. ‘Even though I’m Irish I feel like a bit of an outsider because I trained in the UK,’ she says.

‘Dublin is also expensive,’ adds Dr Mathias, who caveats: ‘But we are getting paid more than in London.’ They find living in a smaller city gives them a ‘nice quality of life’.

They had considered Australia, like many colleagues. ‘The main thing that stopped us was the distance,’ says Dr Mathias. ‘You’d be so far away from friends and family, whereas here I can see the ferry. It’s nice to know we’re 15 to 20 minutes from the airport and can fly back to London in an hour.’

It’s a trip they were used to in reverse when travelling to see Dr Gallagher’s family, who are now just a three-hour drive away which ‘has made the move easier’.

The move also comes with ‘a lot of paperwork’, says Dr Gallagher. As a returning Irish citizen, she had less hassle, but Dr Mathias – despite the common travel area – had to apply for a Personal Public Service number, the equivalent of National Insurance, on top of the family finding a home and transporting personal possessions including a car.

Dr Mathias grew up, studied and worked in London. He admits he ‘would probably have stayed in London forever if I hadn’t met Kathy’, but the opportunity ‘opened my eyes’.

While their move wasn’t made for money, it was when looking at jobs outside the UK that Dr Mathias ‘realised how much other people are getting paid’ elsewhere.

Manageable workload

The workload is ‘a different world’, he says. A typical session involves seeing 12 patients in 15-minute appointments with more time for admin.

‘I come home from work and I’m not tired,’ he explains. ‘In the NHS, I’d often come home knackered. It takes less out of me. I have time to do the job properly, and I’m paid better for it.’

Dr Mathias feels like a ‘more proactive’ GP. ‘If I’ve got an extra five minutes, I might say “let’s talk about your smoking”,’ he says. ‘You wouldn’t do that in the NHS because you’re always firefighting.’

GP Eamonn Jessup left his partnership at a surgery in north Wales in 2015 owing to punitive pension rules. He took locum roles in the UK and Cyprus before trying the Republic of Ireland, which he has now made home as a salaried GP in County Kerry.

He believes ‘GPs are well off’ in Ireland but notes the country’s higher tax levels affect take-home pay – something he acknowledges helps pay doctors’ salaries and fund ‘tremendous’ schools. ‘If you’re going to have decent public services, you’ve got to pay for it,’ he says.

JESSUP: Decided to seek more professional fulfilment

JESSUP: Decided to seek more professional fulfilment

After two fellow partners retired at his busy Prestatyn practice, he concluded ‘I don’t need this’, and decided to focus on finding more professional fulfilment in the twilight of his career with a reduced list size.

In his UK locums, he noticed the service becoming ‘more and more see-and-refer’, recalling: ‘There was no way you could sustain continuity of care.’

Now 68, he enjoys the pace of life in rural Ireland, typically working 9.30am to 6pm, and ‘not counting the numbers’ of patients he sees. He contrasts that with the UK, where as a partner he was typically in from 8am to 6.30pm. ‘You can’t do that into your mid-60s,’ he says.

Appointments in Kerry are 15 to 20 minutes, which gives Dr Jessup the time for a hands-on approach with patients, be it taking bloods, performing ear syringes or stitching – ‘the whole job’.

‘I wanted to work somewhere I could actually do things, like take foreign bodies out of eyes, without sending patients to a specialist,’ he says.

Dr Jessup is more involved in the evaluation of MRI and CT scans and X-rays now, finding ‘astronomical’ levels of incidentalomas. In Wales, he was ‘always told it’s not the protocol’ for GPs to assess scans.

‘It’s a wonderful challenge medically,’ he says. ‘This is the stuff we should be doing in 21st-century medicine. I can get on with the job here, there’s less talk.’

He expects more UK-based junior doctors, frustrated at the dispute with the Government, may be tempted by Ireland, which is expanding its GP trainee places.

‘Culture shock’

Dr Jessup warns those who move must be willing to adapt to seeing private and public patients in Ireland’s hybrid system. Roughly 80 per cent of his patients have medical cards, allowing them free or discounted care. This applies to children under eight and adults aged 70 and over. Cards are also given to some people on a means-tested basis.

Costs for private access vary. Face-to-face appointments are usually about €50; telephone appointments can be cheaper. Many people in this cohort have private health insurance policies.

Dealing with private patients, Dr Jessup explains, can sometimes involve awkward conversations, for example if they don’t require prescriptions. ‘It’s quite hard to pack them out the door with nothing in their hand, saying “you paid for my time”,’ he says. ‘You sometimes have to be quite assertive.’

He also reports a ‘cross-fertilisation’ between public and private care: ‘Say you come in with a swollen knee; I can get you an MRI in two days because I can use a special scheme called direct access, where the Irish Government pays private hospitals to do scans.’

Brand names

Dr Mathias says splitting his time between public and private, which for him is about 50:50, was a ‘culture shock’ at first: ‘It takes a bit of getting used to.’

While he strives to treat every patient equally, he notes ‘a bit of health inequality’ as a result of the system.

‘Sometimes you would like to bring patients back, but some people will struggle to pay €60,’ he says. ‘Or you might recommend a patient had some blood tests done but you know it’s going to cost €30. Sometimes you change your mindset and how you practise a little bit.’

Another subtle difference Dr Mathias has noticed is the use of brand names for drugs in Ireland, rather than their scientific names in the NHS.

Dr Jessup says GP patients at his surgery can get an appointment the same day or next. ‘There’s no 8am rush,’ he says, and puts this down to the ‘unsustainable demands’ on GPs in the UK.

However, he reports the ‘same issues’ with communication between primary and secondary care in Ireland, including IT systems that don’t link up, meaning medication prescribed by a hospital doctor might not be on GP notes.

Dr Jessup is still registered with the GMC but recently gave up his place on the performers’ list. He waited until he was settled owing to the ‘ridiculous bureaucracy’ to get back on, which he believes puts GPs from other countries off working in the UK.

Dr Mathias is still on the GMC register, too. He also gave up his licence to practise in the UK once he knew the move was permanent. Before then, he remained on his performers’ list, working locum shifts at his former practice when visiting family.

HUMPHRIES: Disillusioned with the way the NHS was run

HUMPHRIES: Disillusioned with the way the NHS was run

It’s not just doctors from the UK mainland moving to Ireland. Doctors based in Northern Ireland, where pay has eroded as badly as anywhere in the NHS amid political crisis, are now routinely zipping across the border to work in the Republic.

Consultant psychiatrist Karen Humphries, who lives one mile over the border in Northern Ireland, says she ‘became totally disillusioned with the way the health service was being run in Northern Ireland’.

Living so close to where she works, despite crossing the border, was ‘more good fortune than planning’ but she took advantage of the geography. She says: ‘You bump into a lot of people with Northern Irish accents.’

For Dr Humphries, it was more about the conditions – and leaving ‘an old boys’ club’ culture – than the pay, although she appreciates she now earns at least 1.5 times the salary she would get in Northern Ireland.

‘Within the NHS I felt, to some extent, I was being forced into a position where I had no choice but to underperform, and under-care for my patients,’ she says.

If I wish to structure my appointments so someone is half an hour, 45 minutes or an hour, I canDr Humphries

Part of this was ‘having to jump though 50 layers of red tape’ to sanction treatment she feels should be routine, such as assisting a colleague with their patient.

In the Republic of Ireland, she says she sees more tangible progress in her patients with mental health conditions, which ‘was rare in the NHS’.

‘I don’t have a waiting list,’ she adds. ‘Any referral that is urgent I can see same day or next because I’m not constricted. Nobody can overrule my clinical decision on the urgency of the patient being seen.

‘If I wish to structure my appointments so someone is half an hour, 45 minutes or an hour, I can. I have no administrative pressure, or manager looking over my shoulder saying I have to have 20-minute appointments and see X-number of patients a session. Therefore, I can give the patients exactly the service they need, when they need it, how they need it.

‘We work in a team, we discuss things and the patient gets the intervention they require. Some patients don’t need a psychiatrist, but I still hold the clinical responsibility. I can dip back in again after the psychologist, if that’s appropriate.

‘And if I wish to see a patient every day because they’re acutely unwell and I’m trying to prevent a hospital admission, I’m not restricted by somebody else’s agenda. If the person is sick and needs seeing, they get seen. I get a huge amount of job satisfaction.’

If the person is sick and needs seeing, they get seen. I get a huge amount of job satisfactionDr Humphries

She insists: ‘I am still a passionate believer in the NHS as it was designed and constructed. Unfortunately, it has become management-led as opposed to clinician-led. That’s the biggest difference. [In the Republic of Ireland] it’s clinician-led, manager support. If I have an idea, they help me get it over the line; that was always lip-service in my old job.’

While the majority of Dr Humphries’ patients qualify for free public treatment, she says not all drugs she might prescribe are covered on their medical cards, ‘which hinders me a little bit’.

‘You have to be mindful of that,’ she adds, explaining: ‘Sometimes you switch your drug to one you know will either be free or cheaper. But if it’s clinically necessary, there is a hardship scheme [where patients can be reimbursed].’

The limits on availability of drugs, she says, must be weighed up against a ‘much higher standard’ of therapeutic relationship than she felt able to give in the NHS – so ‘does not impact quality of care’.

Dr Humphries has given up her licence to practise in the UK because of ‘logistics’ and cost but retains her GMC registration – which means she can continue with medico-legal work.

Close but distant

She says moving to the Republic is ‘a bigger psychological jump for somebody from England than somebody from Northern Ireland’ because ‘we’re used to crossing the border without even thinking about it’ whereas it could be a ‘massive cultural shift’ moving from the UK mainland.

Northern Irish doctors can also ‘play the double card’, to make transitions easier, she adds, noting that Brexit has made things ‘more difficult’ for doctors moving from Great Britain.

‘For consultants in Great Britain, their qualifications are not necessarily deemed in the same way they once were,’ she explains.

‘It used to be that as long as you had your medical degree and GMC licence that was it. Now, because Ireland is still part of Europe, UK qualifications are not an automatic right.’

Dr Gallagher notes that Ireland is also ‘haemorrhaging’ its own doctors, who have the same temptations of moving to Australia, New Zealand (and the UK). But she says a long-standing culture of moving abroad within Ireland means many doctors tend to ‘float home’ eventually.

She was ‘never 100 per cent’ about moving back but with NHS conditions deteriorating and a job opportunity in her ‘niche specialty’ presenting itself she ‘went for it’. Now, with everything in place for their young family, they are there to stay.

Dr Mathias adds: ‘We said we’ll give it a year and see how we look. And we both really enjoyed it. A lot more people are asking us what it’s like in Ireland and saying “maybe we’ll move in a few years”, especially since the new [Irish consultant] contract. People are more interested than they were a year ago.’

But he warns: ‘It’s not a utopia. There’s plenty over here to frustrate you too. Neither system is perfect by any means. A lot of people in the UK think the grass is greener and want to go to Ireland to get paid much better. People in Ireland complain about the system as much as people complain about the NHS.’

In the week leading up to his conversation with The Doctor, Dr Jessup said he had been contacted by two UK-based doctors asking him about life in Ireland. He agrees the system in Ireland is ‘far from perfect’ but appreciates the job he has – and believes with the right changes the same lifestyle could be achieved for GPs in the UK.

‘I’ve got a good salaried contract at a fantastic practice in a beautiful part of the world. And I’m loving it.’

(image credit: Brian Morrison)