As with much of the nation, I am reeling from the effects of a TV drama series.

In It’s a Sin, writer Russell T Davies draws on his own experience to tell the story of five gay friends living in London through the AIDS pandemic of the 1980s. And the atmosphere he creates is so powerful that I find myself transported back nearly 40 years to my own experience of AIDS, not as a gay man but as a GP who bore witness to countless stories of suffering and death, some eerily similar to the ones which were playing out on my TV.

Reports began to emerge, in 1979, of increasing numbers of young, gay men in the San Francisco area falling prey to illnesses normally associated with a defective immune system.

At first, it was called the ‘gay plague’. It was not long before we would hear US evangelical pastors, politicians, and even senior medical figures tell us these men were ‘architects of their own destruction’.

I told him he was welcome at my practiceDr Glascoe

The medical response to it was at first deplorable. We had, after all, plenty of experience of dealing with blood-borne infections, in particular hepatitis B, which spreads in exactly the same way as AIDS, but when it came to AIDS I noticed some doctors deploying bigoted and judgmental attitudes.

One of my AIDS patients had been due to have a routine hernia repair, and had been booked into his hospital bed in the usual way. But when a senior registrar arrived on the ward and glanced at his medical notes he exploded.

‘What’s HE doing here?’ he demanded of his accompanying nurse. Without waiting for a reply and refusing even to look in his direction he shouted for all the ward to hear:

‘Get him out of here now, sister. I will not have patients like him on my ward!’

Offering comfort

‘Oh my God it’s the man with AIDS!’ yelled one of the receptionists the moment she saw him. I told him he was welcome at my practice and I and my team would treat him no differently than any of my other patients.

And I asked him to spread the word among his gay friends I would also welcome any other gay man or AIDS patient who had experienced similar discrimination from the medical profession.

GLASCOE: Pictured in the 1980s

GLASCOE: Pictured in the 1980s

One by one they came with their horror stories, not unlike the one inflicted on one of the characters in It’s a Sin, who, no sooner is he diagnosed than he is whisked away and locked up in an isolation hospital, under archaic legislation designed to stem the spread of cholera.

Apart from being furious with my colleagues who had behaved so despicably, my predominant emotion at the time was that of utter helplessness. Beyond bearing witness to their plight, I could do very little for these people, and at the time, neither could anyone else.

At least I could do something, even if it meant only putting an arm round a shoulderDr Glascoe

But there was something I could do. A friend once defined the role of a doctor in these terms: ‘To cure sometimes, relieve often, and comfort always.’

In those early days the first option was out of the question. As for the second, even treatments to alleviate suffering were limited; even considering the recent advances in palliative medicine, people often died in terrible pain.

But comfort: here at least I could do something, even if it meant only putting an arm round a shoulder, or simply giving a good old-fashioned hug.

This meant a great deal to these people who were far more used to being shunned. And perhaps it meant even more coming from a doctor. It showed them I wasn’t afraid to touch them.

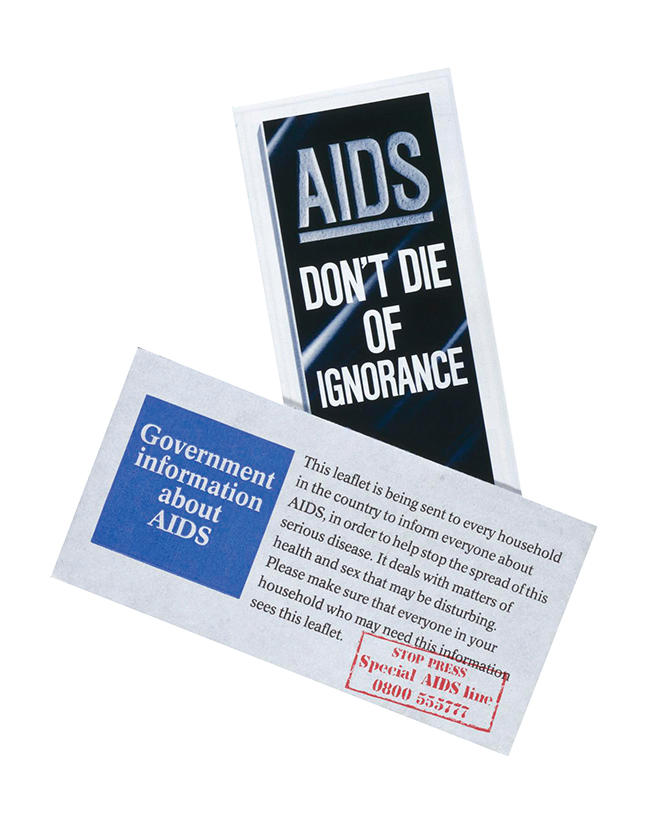

Credit: The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Credit: The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

You don’t get AIDS by touching an infected person, or even kissing them, although many people didn’t know that at the time.

In 1982 one of my haemophiliac patients, Huw, came in to ask what a series of purple-ish blotches which had appeared on his skin might mean. He said he thought he might need an HIV test.

It turned out Huw was the first patient in my practice, and one of the first in the UK, to have contracted AIDS from a blood transfusion. For some time the UK had been buying in Factor VIII concentrate from the USA, much of which had been derived from the prison population.

Later this plasma was screened and the problem was avoided, but in the interim thousands of haemophiliacs all over the world died of AIDS. My patient was one of the early ones. Huw was dead within 18 months of that first fateful encounter in my surgery.

Mother and child

Around the same time I had a young woman patient some to see me. Heather was what doctors call a poly-drug abuser, although she had resisted injecting them until she formed an unfortunate liaison with a hardened IV drug user who introduced her to its delights.

And naturally enough, as lovers do, they shared everything.

She too came in and showed me the tell-tale signs of Kaposi’s sarcoma which had appeared on various locations on her body.

My heart sank as I realised what I was looking at and advised her to have the test. It was positive of course; worse still, if such a thing is possible, her pregnancy test proved positive as well. Heather’s progress was entirely predictable.

Her baby was born with AIDS, and died within a few months. She followed her baby less than a year later.

credit: getty

credit: getty

I did my best to shut myself off emotionally from the tragedy, as doctors are tacitly encouraged to do, but this proved impossible.

Yet there were survivors too. Of the people who tested positive in those killing days, a few, amazingly, are still alive today. I think particularly of a man called Iorwerth.

Softly spoken and self-effacing, he radiated a quiet charm. He first tested positive in 1983, but his t-cell count remained consistently high.

And when anti-retroviral treatment finally became available, he responded well and his viral load fell away almost to zero. Nature rarely obliges us in that way.

I am grateful to It’s a Sin for stirring my memories and, more importantly, for educating a huge cohort of people too young to remember what happened 40 years ago, in the time of another great pandemic. Their stories must be told, lest we forget.

Stephen Glascoe is a retired GP from Cardiff