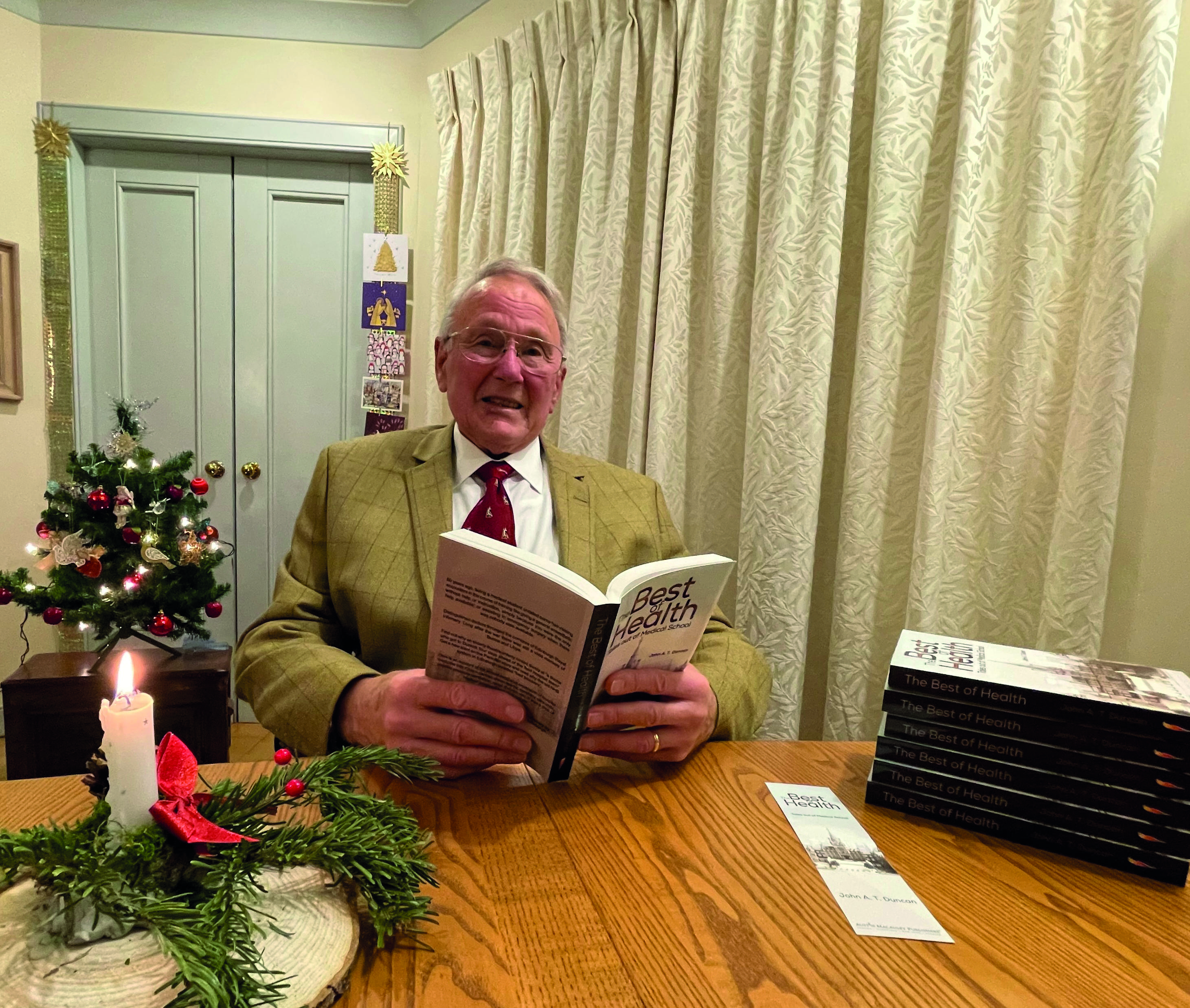

Consultant anaesthetist and GP John Duncan published his first book at the tender age of 88. His memoir, The Best of Health, paints a vivid portrait of life as a medical student

John Duncan

John Duncan

It was an article in the BMJ that suggested medicine as an alternative career after the Suez Crisis forced the closure of the Duncan family pottery in Stoke-on-Trent. The dean of medicine at Edinburgh University was keen to recruit ‘from non-scientific backgrounds’.

John Duncan applied and was accepted without an interview. Dr Duncan’s descriptions of Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, a world-class teaching hospital, depict a cloistered world where juniors were treated like ‘prize poultry’.

The residents’ mess served them three meals a day and had a butler. ‘The… belief was that well-fed young people work better than hungry ones,’ he writes. Laundry and shoe-polishing were included. These were optimistic days when the NHS was in its infancy and where men – mostly men – who had been schooled in the theatre of war were pushing at the boundaries of science and surgery.

Anaesthesia for children undergoing open-heart surgery at the time included lowering them into ice baths to slow their heart rate. One of his surgeons, James Sneddon Jeffrey, had been involved in the earliest trials of penicillin in war wounds in North Africa.

‘In Sir Derrick Dunlop’s introductory address to us in October 1957, he said, “I envy you young doctors the ability to prescribe for your patients the treatment they need, rather than what treatment they can afford”. His words have stayed with me ever since.’

Medicine was evolving fast and Dr Duncan witnessed some difficult births. The first call out of Edinburgh’s surgical flying squad, precursors to paramedics, was to a window-cleaner impaled on railings. The ‘crash hamper’ of emergency care essentials was a giant laundry basket which proved too big for the ambulance, a converted bread van.

The patient survived but the flying squad was mothballed for a decade. Dr Duncan’s passion for writing was triggered six years ago when he wrote daily emails about their shared wartime childhood to his dying brother, Gregor.

‘Writing those emails became a daily discipline of memory, unlocking rooms in my mind that, once opened, seemed remarkably bright and free of dusty neglect,’ he says. The prospect of a medical school reunion gave added impetus. Dr Duncan is keen to commit to memory what he calls the ‘golden age of the health service’ – as a marker of what was once possible and how far we’ve come.

The foreword to The Best of Health says it contains ‘a moral lesson’ too, about the need for transparency and openness. Without these, an unreported blood sample contaminated with Hepatitis B was able to infect medical staff and patients, with several fatalities.

By contrast, the monthly ‘death meetings’ in the surgical lecture theatre, where senior doctors discussed difficult cases for mutual learning, were key to a young doctor’s education.

‘The search for truth was more important than where to lay the blame,’ says Dr Duncan. ‘Medicine generally runs best on coordination and cooperation, not competition.’

GP Jo Cannon turned to creative writing as a way of helping her to process complex cases and better understand difficult patients

Jo Cannon

Jo Cannon

Being in general practice in multicultural Sheffield has meant a varied case load – and rich fodder for her fiction. In her professional life and her writing, Dr Cannon has tended to side with the outsider, the stranger, the struggler, and has sought to understand their backstory.

The three years she spent in west Malawi with VSO (Voluntary Service Overseas) in the late-80s fuelled this fascination. It was a tough training ground – and a window on an extraordinary world she’d spend years trying to make sense of, including through storytelling. Newly qualified as a GP in the UK, she became ‘district health officer’ for Mchinji, near the Zambian border – responsible for everything from obstetrics to tropical diseases.

Caesareans were memorably medieval, sometimes involving funnels and sieves, and her ‘clinical assistants’ had the most basic of training. And a silent killer was on the loose: HIV. ‘It was spreading rapidly and the suffering was extreme,’ says Dr Cannon. ‘All the staff were dying: the dentist, the chemist, all the young people. When I raised this with the visiting minister of health, she said: “This is restricted information: you’re not to do anything with it.”’

This international perspective, and a love of the BBC World Service, has helped her connect with migrants and those on the margins. Many have traumatic backgrounds, some challenging behaviour. ‘GPs hear a lot of trauma but we don’t have any formal means of dealing with it – and a friend told me about a reflective writing group for GPs that was for “increasing empathy with difficult patients”.

I’ve been writing ever since. ‘I’ve had the most demanding patients, with unstable emotions and attachments, and it can take a long time to discover they were actually torture victims suffering post-traumatic stress.’

Insignificant Gestures explores difficult themes, from domestic violence to obsessive compulsive behaviour. But its stories also celebrate the healing power of love and acceptance. An account of a transgender woman’s smear test embraces both.

Where fictional characters are inspired by real patients, they are always composites. One of the most helpful exercises Dr Cannon employs in her stories is to ‘try to write the consultation from their point-of-view’. ‘You ask yourself: What do they really want? Why are they endlessly seeking help and rejecting it?’ Over 30 years in general practice Dr Cannon has had the privilege of journeying with patients through dark periods – and seeing them emerge at the other end.

The ‘decline of continuity of care’ these days, however, means she may no longer see ‘what happened next’. Writing fiction allows her to administer a prescription, a solution – even if in reality situations remain unresolved.

‘Sometimes, after a surgery, you’re left sitting with emotions, even if your patient tells you they feel much better after seeing you. In writing you can always have things come right in the end.’

Intensive care consultant Aoife Abbey used her writing to open a window on a world most people rarely see. She wrote Seven Signs of Life while still a trainee

Aoife Abbey

Aoife Abbey

For Dr Abbey, writing has been the headspace that has enabled her to navigate the uncertain, uncontrollable intensity of ICU. A difficult case while she was still a foundation doctor prompted her to submit a piece to the forerunner of The Doctor, which led on to a BMA blog under the guise of ‘The Secret Doctor’, which led on to her book.

Seven Signs of Life explores the maelstrom of emotions encircling staff, patients and families, and corrals them into key themes: grief, anger, joy, fear, distraction, disgust and hope. It’s an honest and frank reflection of her wrestling to respond well to patients’ and families’ fears, to make sense of their suffering. She grapples with hope, refusing to dispense it blindly.

‘I can think of few responsibilities greater than handing somebody hope,’ Dr Abbey writes. It charts her journey towards learning to sit with people’s fear without trying to ‘reshape it’, and accommodating herself with death, as a part of life. And she talks frankly about the things she can’t resolve, about mistakes. She writes, it seems, to refuse cynicism, to stay alert to her feelings. ‘I write to challenge myself and my understanding of things,’ she says.

‘I write to pay heed to the experiences I share with people.’ Dr Abbey writes for those who will probably never visit her workplace. ‘Before the pandemic, public awareness of what intensive care was and what happens when you walk through those doors was minimal. I felt there was some value in bringing people inside that, mainly to point out the people at the heart of it all and how much we all have in common.’

Understanding different perspectives is vital in a role that constantly demands ‘patient best interest’ decisions. It’s why Dr Abbey loves, and recommends, reading. And part of her aim in writing is to offer a different narrative and standpoint from the one that she feels medicine more typically presents.

That can make writing feel risky – especially as a relatively young woman in a male-dominated specialty. ‘I receive such wonderful support from the people I work with,’ says Dr Abbey.

‘But there is this cult of what it is to “be a doctor”, how we think a doctor should look or speak, and what we should value. Being who you really are – and being a doctor – shouldn’t be about “breaking a mould”. ‘Things are getting better, but I still have sleepless nights each time I write something.

It can feel like we’re at risk of losing the currency of professional esteem at any minute. ‘Modern medicine is miles away from where it was 50 years ago, but we still have a way to go to foster a culture which is undeniably supportive for everyone and which makes space for individuals.

Many of our systems continue to reward and make it most safe for those fitting specific norms to be at the fore, both internally and publicly. We don’t yet treat all doctors and future doctors equitably.’