A colleague took a sabbatical to work in Shetland last summer, planting an idea that germinated during the next few months as I contemplated retirement.

I was happy to escape the routine of everyday practice, but not quite ready to stop completely. There is a shortage of GPs across the country and the NHS has called on retired doctors to help. So, this summer, my wife and I set off to job share a maternity locum in Orkney.

After the long drive north, a seven-hour ferry crossing from Aberdeen to Kirkwall and a noticeable drop in temperature, we found ourselves nervously standing outside The Balfour Hospital where we would be working. This new building, one of the first zero-carbon hospitals, is welcoming and open, with Scottish folk music playing in the background.

It opened just before the pandemic and still looks fresh – not yet spoilt by the NHS’s tendency to let posters and notices clutter up any available wall space. We walk through to the practice reception, receive a warm welcome and are introduced to several of the team. I try to clock their names, but know I’ll soon be asking them again. We get our key tags – essential for getting around the building.

Shall I record my experience with the Vision computer system? I suppose I must, but I don’t want to be a stuck record, grumbling about its clunky and fragmented architecture. Each module – making appointments, consulting, using clinical tools to assess risk or reading hospital letters – seems to have been designed independently and the system doesn’t offer the integration that English GPs increasingly take for granted.

Prescriptions, which in England would ping electronically over to the patient’s chosen pharmacy, need to be printed (don’t forget to press F9 twice) and given to the patient.

Clare Goodhart and Jonathan Graffy

Clare Goodhart and Jonathan Graffy

A retired GP told us the developers of SystmOne wouldn’t customise their offer for Scotland, but I don’t know the ins and outs of how the two countries’ primary care systems diverged. In IT, perhaps the smaller nation is slipping behind, but in other ways, there is much England can learn from Scotland.

Relying on people who know what they are doing, stay in their roles and want to get things done right can go a long way to make a health service work well. Examples would be the friendly accreditation process NHS Lothian offers doctors wanting to work in Scotland – compared with the nightmare system Capita runs for the English NHS, or the easy way the lab staff in Orkney accepted a late specimen collected in the wrong container.

So, after an hour’s induction, armed with a print-out telling me how to navigate the computer and a welcome cup of coffee I start my first surgery. Within an hour I’m running 45 minutes late. One of the partners tactfully checks if I’m aware of the patients waiting. A four-month gap since I last consulted, navigating the system and working out what the local services offer is taking its toll. I had better speed up.

It's always wrong to generalise about patients, but I’ll try to capture some of the interactions I’ve had. Quite often consultations begin with an intro about what Clare and I are doing at their practice – and most are welcoming, hoping we enjoy our time in Orkney.

Perhaps also there is a softness in how people relate – as if living in small community helps people accept each other and get along. Maybe people are more stoical – certainly the farmers seem to be. One older man who had put up with a probable skin cancer comes to mind. But Orkney does have worriers too.

As a locum it’s easier to sort out acute problems than make a sustainable contribution to managing chronic conditions, but inevitably an outsider sometimes sees how things could be done differently. I’ve seen a couple of people whose diabetes had slipped off the agenda and needed sorting out.

All prescriptions in Scotland are free and there is less imperative to encourage patients to obtain their own ‘over-the-counter’ medicines. We wondered if this sometimes led to a more paternalistic doctor-patient relationship. Certainly, very few patients had bought their own blood-pressure monitors.

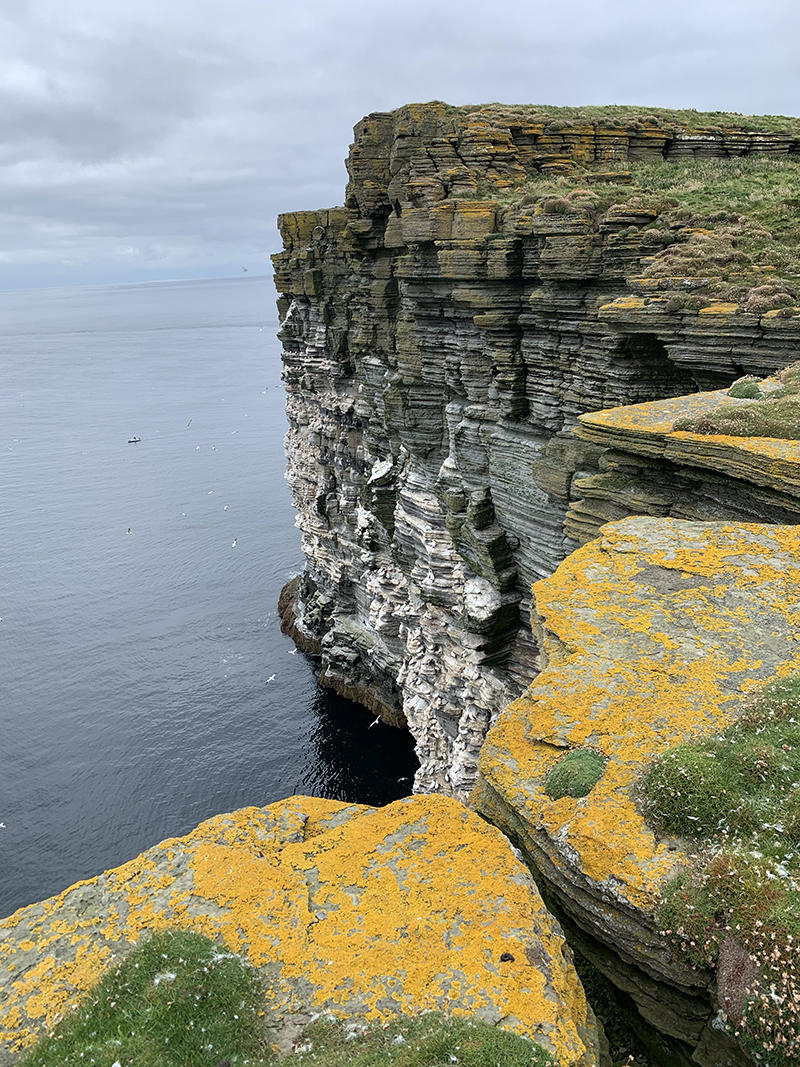

Cliffs on the Island of Westray

Cliffs on the Island of Westray

Some specialties are locally based, but for others (neurology, orthopaedics, oncology etc) patients need to go to Aberdeen. Families have access to hostel accommodation when visiting relatives in hospital on the mainland, but despite COVID changes we haven’t seen much evidence of telemedicine in the delivery of specialist services.

But when outreach works it does so, well. One morning I went into the coffee room and met a paediatric ENT surgeon from Glasgow and her specialist nurse colleague. They had come up to Orkney to train the practice staff, the hospital emergency department team and ambulance services in managing tracheostomy problems in a young child they had just discharged. That baby had the best discharge planning I have ever witnessed across the NHS.

NHS Orkney has faced criticism for its mental health services – in particular, the safety of patients awaiting transfer to Aberdeen in crisis situations. That much is fact, but we’ve not seen much of the services meant to support patients with mental health problems.

Fortunately, a new psychiatrist has been appointed, so hopefully things will improve, but there does seem to be to be quite a lot to do.

A recurring question in providing care to remote islands is how much care should be provided on the island and how much should depend on patients travelling when ill. Most islands have a full-time nurse practitioner, but GPs only visiting once a week.

On islands with under a hundred residents that may seem a bit of a luxury, but it provides a sense of security. Papa Westray has only 65 residents but boasts three defibrillators. As we cycled past the community centre there, we were alarmed to see a crowd outside.

A paramedic and nurse standing in the street – it looked as if someone was seriously ill. Later we met them again on the ferry home and learnt they had been training locals in resuscitation skills. Much better to embed the skills in the community than rely on a response from across the water. Especially if there is stormy weather and the ferries cannot sail.

In the past we have tended to keep quiet about being doctors on holiday, noticing the information frames how people respond when you first meet. But this time it’s the other way round – working in the community and making a part-time contribution has made it easier to connect with people than if we were just paying a short visit to the islands. So, we are a bit more open in discussing our busman’s holiday. Should we be clinging on to our skills as GPs? Why not? We have found it is a ‘win-win’ formula; a cost-neutral holiday in a place we have always wanted to visit.

These notes are just a snapshot and say nothing about the towering cliffs with sea birds nestling in their crevices, the neolithic stone houses that could still be habitable if you put the roof back on, or the fantastic meals we’ve treated ourselves to. Orkney has a strong community and offers tourists (medical and otherwise) the chance to see life at a different pace – where everyone has their own contribution to make.

Married GP couple, Jonathan Graffy and Clare Goodhart worked as part-time locums at the Heilendi Practice in Kirkwall, Orkney, during August and September 2022. Setting this up involved joining the NHS Scotland performers list and arranging indemnity cover for practice in Scotland. The practice helped find accommodation locally. Advice for retired doctors considering returning to practice is available from the BMA. The Scottish Rural Medicine Collaborative organises a scheme to match GPs to practices looking for short-term cover.