Hope is a powerful thing. For now, it’s sustaining the doctors working in Kabul’s hospitals – even despite running short of bandages, blood products, antibiotics… everything.

The supply of COVID vaccines has dried up and they are reusing disposable personal protective equipment again and again. Most of the doctors in Afghanistan whom Waheed Arian supports have resisted the temptation to join the exodus after the Taliban takeover in August.

These doctors want to believe things can improve. But hope can’t run on empty. ‘The border is closed, food and medicine are running out, prices have sky-rocketed,’ says Dr Arian, a former Afghan refugee now living in Cheshire.

‘They are still working – the female doctors too – but they are all terrified. ‘Doctors haven’t been paid for months. One texted me and said: “I don’t want to leave the country but I need to find another job.” And that breaks my heart.’

One of the biggest risks to the healthcare system in Afghanistan – and the morale of its workers – is international isolation. Doctors fear they might lose not just humanitarian support but also the window on to another world, the prospect that things might improve in Afghanistan too.

So, alongside his work in emergency medicine in the UK, Dr Arian uses telemedicine to support his counterparts in his homeland.

‘We need to tell them that we haven’t abandoned them. It feels like everyone has left, and we’re telling them we’re still here, supporting them. We shouldn’t underestimate how important that is.’

The fight for survival

Dr Arian’s own extraordinary story illustrates vividly how decades of conflict and political turmoil have robbed Afghanistan of a functioning health system and human capital. Dr Arian had wanted to become a doctor since he was five.

After years of ‘hiding in cellars from the daily rockets, bombs, shelling and jets in the sky’ during the Afghan-Soviet conflict, the family fled to Pakistan in 1998. His father was a conscientious objector, and evaded conscription by hiding in Logar province.

The rest of the family had stayed in Kabul, Dr Arian’s mother depending on rental income and friends to feed her children.

‘Military service meant being sent to the front line and that was usually a death sentence,’ says Dr Arian. ‘There were Afghans on both sides of the conflict, and my father didn’t want to fight Afghans.’

LIFELINE: Dr Arian advises a doctor in Afghanistan

LIFELINE: Dr Arian advises a doctor in Afghanistan

Pakistan was a chance for the family to be together – but it was treacherous too. To reach Peshawar, they travelled at night through the mountains in a caravan of horses and donkeys, along the weapons-supply route for the Mujahideen.

Dr Arian only survived a Soviet helicopter gunship attack because his father hid him in a bread oven. Within days of arriving at the Babu refugee camp, they caught malaria. Soon, Dr Arian fell ill with tuberculosis.

‘The conditions in the camp were absolutely inhumane. There were big families living in tents, in 45-degree heat, with hardly any food, clean water or sanitation. Many people died of malnutrition and malaria.’

The camp doctor gave Dr Arian odds of 50:50 that he would survive because he was so malnourished. But, noticing the boy’s fascination with his X-rays, and the absence of any toys, he also gave him a stethoscope and an old medical textbook.

A sustaining ambition

In 1991, they returned to Kabul, because Dr Arian’s father was beyond the age of conscription. For a year, things were calm.

‘For the first time ever, I had a ball to play with and started going to school, so I was very happy.’ But within a year, the civil war had entered a new phase as the Mujahideen ousted the Soviet-backed president, Mohammad Najibullah.

‘It was a street-by-street fight so we were hiding in cellars again, fleeing from one part of the city to another, stepping over dead bodies and dodging bullets.’

His education faltered again, fuelled only by the few books his father could find, and classes in the refugee camp in Pakistan where they fled again as the fighting in Kabul intensified.

'Good soldier'

When depression descended on Dr Arian at the age of about 10, what sustained him was ambition, and snatches of ‘an alternative reality’ glimpsed through the BBC World Service and the occasional Hollywood film – not the sedatives his doctor prescribed.

‘Sedatives made me sleepy and in wartime you have to be on your toes. So, I’d hang on to the hope that one day I would go to school, have friends and become a doctor – even though I didn’t know how.’

Unwittingly it was the Taliban who propelled Dr Arian into fulfilling his dream. By his early teens, he was helping his dad run a taxi service and the Taliban often took rides.

It feels like everyone has left, and we’re telling them we’re still here, supporting themDr Arian

'I remember them saying: “Would you like to fight with us? You could be a good soldier.”’ Then a rocket attack on their neighbours’ house wiped out that entire family.

Dr Arian’s parents decided it was time: they sold the house and possessions to raise £7,000 to buy their son what they thought was legitimate passage to London, where they had a friend.

‘The dream was to become a doctor in Afghanistan but all those doors were shutting on me. The country was isolated.

I couldn’t get into medical school: we were not privileged enough. So, my parents sold everything to get me out.’

When he arrived in London, just 15 and with £70 in his pocket, he was sent straight to the Feltham Young Offender Institution. His papers were false.

Three jobs and study

For the next three years, Dr Arian held down three jobs – as kitchen porter, cleaner and shop worker in London – and studied for A-levels in the evenings, as his autobiography In The Wars recounts.

It was years later that Dr Arian diagnosed his hyper vigilance back then, his sensitivity to the sound of the Tube, his visions of tanks in the street. This most recent Afghan crisis has triggered his PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) and cost him sleepless nights.

He read voraciously in the house he shared with other refugees, then started taking evening classes and exams. He did well and decided to aim high: Cambridge.

WAR-TORN: Abandoned Soviet tanks litter Panjshir province, Afghanistan (Getty)

WAR-TORN: Abandoned Soviet tanks litter Panjshir province, Afghanistan (Getty)

‘My colleges discouraged me from applying and, though I was pretty humiliated by that, it just made me more determined to prove them wrong.’

He won a place to study medicine at Cambridge, did his clinical training at Imperial College London and won a scholarship to do an elective at Harvard. It was when he was a junior doctor in London and Essex that he started to combine trips to his family in Kabul with visits to five local hospitals.

He was shocked to realise how basic the health service was. ‘Afghanistan’s education system is very outdated, there’s no capacity to train specialists, and doctors don’t have the opportunities to train abroad. The brain drain means many have left the country.’

Tech facilitation

Dr Arian noticed that colleagues in the UK were fascinated by his stories from Kabul and wanted to help. But it was too dangerous for them to visit.

He had also started to realise the potential of telemedicine, noticing the ease with which scans and reports were transferred between hospitals, even internationally, during his radiology training in Liverpool.

Even if Afghan hospitals did not have presentation technology, doctors had smartphones with Skype or Viber.

Collaborating closely with the Afghan Ministry of Public Health to establish a strong clinical governance framework, he set up Arian TeleHEAL in 2015.

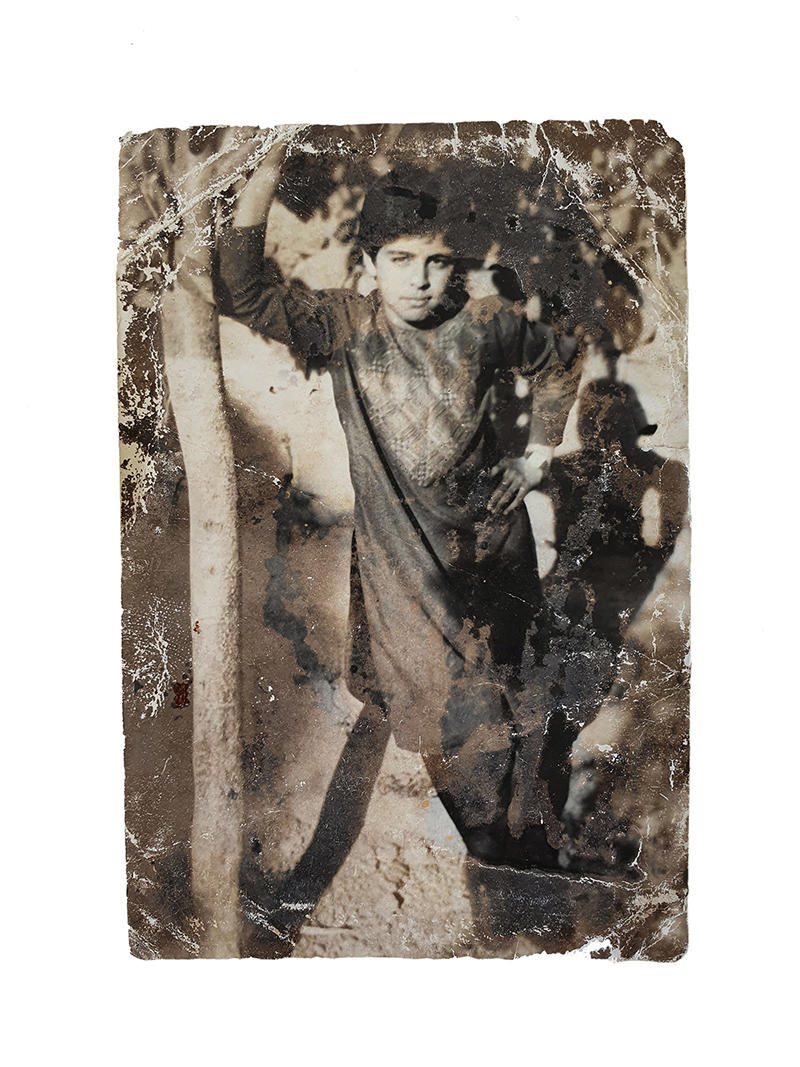

EARLY AMBITION: A young Waheed Arian who chose to pursue medicine from the age of five

EARLY AMBITION: A young Waheed Arian who chose to pursue medicine from the age of five

Six years on, the charity is supporting emergency departments in 14 hospitals across Afghanistan, with case-based discussion, guidance and training seminars provided by an international network of 150 volunteer specialists.

‘Doctors send us scans and medical details of the cases they’re dealing with, whether it’s a bomb blast or serious illness, and I allocate them to one of the specialist groups of volunteers we have according to their specialty,’ he says.

Arian TeleHEAL has since partnered with other governments and charitable organisations to set up telemedicine initiatives in several nations including India, Syria, South Africa and Uganda.

It has won Dr Arian many awards, from the UN Global Hero Award in 2017 to The Sun’s Who Cares Wins ‘Best Doctor’ award last month

Kindness and solidarity

For now, Afghanistan is in purdah politically, its future veiled, its economy in crisis. At the time of writing, hospitals had a week’s worth of supplies left, with strict rationing in place. Some 3.5 million displaced people face a fierce winter without shelter or warm clothes.

Dr Arian is adamant the UK Government needs to engage with the Taliban to ensure safe passage for continued humanitarian support.

‘You have to differentiate humanitarian engagement from political engagement. You can’t punish the Afghan people, with 15 million of them living in poverty.’

Since the Taliban takeover, Arian TeleHEAL has stepped up its support in Afghanistan and Dr Arian has campaigned for proper support for Afghan refugees arriving in the UK, as the BMA has also done.

You can’t punish the Afghan people, with 15 million of them living in povertyDr Arian

His charity is appealing for mental health professionals to volunteer to support doctors in Afghanistan and new arrivals to the UK, many of whom are suffering from PTSD as he does. What will make the difference for Afghan refugees – and doctors in Afghanistan – is kindness and solidarity, he believes.

Dr Arian knows that the compassion of others sustained him – from strangers in Kabul who sheltered his family during bombing raids, to the barrister who fought to free him from Feltham.

‘Our doctor colleagues in Afghanistan are not requesting a better life or better things. But they know their country will be extremely isolated. More than ever, they need moral support. It means the world to them that the international community is still in touch with them.’

Images courtesy of Waheed Arian