Things are about to change for Mridul and Saroj Datta.

The couple have made it their life’s work to run the general practice in Blackburn that Mridul set up 51 years ago. They have been GPs to four generations of some families and, at 82, they are still working. But Saroj Datta has decided to retire next March.

It’s not going to be easy: when she was on leave recently following surgery, patients kept asking for ‘Auntie’. Her husband, Mridul Datta, is not ready to quit, however. His own father, an obstetrician in India, set the bar high.

I feel I’ve still got a lot to contribute, including teaching younger doctorsDr Datta

‘The day my father died, he saw four patients that evening. And he was 85 and a half. He insisted on the half.’

Drs Datta are exceptional but not unique: there are more than 15,700 doctors over the age of 65 in the UK who are still licensed to practise with the GMC. Doctors are retiring early in their droves, their hand often forced by unsustainable workloads, burnout or the pension tax trap.

But many continue well past retirement age, contributing in many different ways. Because, as most will tell you, being a doctor is far from just a title.

‘Patients were like family’

For Drs Datta, general practice is a ‘vocation’. That’s how they have sustained a busy practice in a multicultural community for five decades, much of it with only locum support.

They came to England in 1965, initially just for their postgraduate training in obstetrics and gynaecology, but then stayed. They became fellows of their medical royal college but consultant posts for international medical graduates were rare.

Mridul set up in general practice in 1971, in a converted terrace house. Saroj joined him in 1975, after a stint in public health. They started from scratch and their caseload grew quickly. They were on call 24/7, often did home visits and had three children.

For 14 years, Mridul was also running gynaecology clinics locally and working as a locum consultant around the country.

Once a doctor, always a doctor. It’s very much part of your identityDr Singh

Their ability to connect culturally with immigrant communities and Saroj’s four languages meant patients have remained loyal.

‘Patients were like family in those early days,’ says Saroj. ‘And the ones that have stayed with us from that time still have the same relationship with us. ‘In general practice, it has been said that half of the patient’s illness goes if they feel you are part of them, that you are really listening.’

Mridul reduced his hours a few years ago – but he missed full-time work. ‘I did not pressurise him: Gordon Brown did,’ Saroj says. But Mridul still works eight sessions, and Saroj is down to four, although she still does much of the admin.

For Saroj, it’s the relationships that are hard to walk away from, including her team, but she knows it’s time to ‘hang up her boots’. Mridul, meanwhile, a fourth-generation doctor, resists his family’s repeated calls for him to retire: medicine is inextricably bound up in his identity.

‘If I became a danger to my patients, I’d retire that same day,’ he says. ‘But I feel I’ve still got a lot to contribute, including teaching younger doctors. A trainee from Iraq told me: “In our country, they say: When the fire is out, life is not worth living.” I take that as a challenge.’

Return, retire, return

The first time Jo Cannon retired was at 58, the culmination of a stressful, demoralising year.

The inner-city practice where she was a senior partner underwent a CQC (Care Quality Commission) inspection, and for the first time in her career, she was summoned as a witness at a coroner’s inquest, twice in six months.No blame was attributed to her, but it took its toll.

‘I took it all quite personally and was running out of steam,’ says Dr Cannon. ‘Then a friend of my age retired, and it was almost like an epiphany.’

CANNON: ‘I wasn’t ready to leave medicine’

CANNON: ‘I wasn’t ready to leave medicine’

She joined the NHS GP Retention Scheme, aimed partly at doctors around retirement age, and for two years did four sessions a week at a different practice, within cycling distance of her Derbyshire home.

She retired again in February 2020 – but within weeks had responded to the GMC’s COVID call-up. ‘I realise now I wasn’t quite ready to leave medicine, given how quickly I responded,’ Dr Cannon says.

‘My heart was still in it.’ Since then, she’s been back at her old practice, now working two sessions and focusing entirely on patients, not paperwork.

The requirements – CPD (continuing professional development) and supervision – are far from onerous.

Time is factored in for CPD: her mentor is an old friend.

‘Now I’m doing the best part of the job and my colleagues see me as a bonus. It’s just very hard to let go of the last bit. Next year I will reduce to one session a week. I’m fading away like the Cheshire cat.’

‘Cushion the fall’

Jonathan Graffy also enjoyed the phased withdrawal that the GP Retention Scheme allowed him for 18 months before he and his wife, Clare Goodhart, retired officially in March, both in their mid-60s.

But Dr Goodhart had been a partner at a Cambridge practice right up to retirement and feared it might be like ‘falling off a cliff edge’. So they began looking for ways to ‘cushion the fall’, keep their hand in and retain their skills.

A working holiday on Orkney, job-sharing a maternity locum, provided the perfect opportunity. ‘We both felt we’ve got all this knowledge and experience and it was a waste to stop altogether,’ says Dr Goodhart.

‘We were very aware there’s a shortage of doctors and if we could help with that, it would be a win-win.’

GOODHART (LEFT) and GRAFFY: Keen to keep their skills updated

GOODHART (LEFT) and GRAFFY: Keen to keep their skills updated

They had to join the NHS Scotland Performers List, undergo safeguarding training, and arrange indemnity insurance, but onboarding was straightforward.

They spent five weeks, each doing four sessions a week, supporting a GP practice in Kirkwall. It was a steep learning curve, but they had good support, and felt valued.

‘We didn’t want to undermine the practice in any way or take a different approach,’ says Dr Graffy, ‘but we were a fresh pair of eyes. There’s nothing more rejuvenating than starting from scratch and learning new skills.’

And their work meant they were welcomed and gained a much better picture of community life than the average tourist. ‘Being a GP is a licence to curiosity,’ says Dr Goodhart.

Sense of camaraderie

On his last day at work as a consultant surgeon in King’s Lynn in 2016, Surjait Singh’s daughter asked the kind of question only a daughter can ask.

‘So, Dad, is this right? When you go into work today, all the people in the hospital will say, as they always do, “Good morning, Mr Singh.” But when you walk out, you’ll just be an old Indian bloke carrying a briefcase?’ Mr Singh recalls the conversation with wry humour.

‘Very perceptive: that’s how quickly it changes. But once a doctor, always a doctor. It’s very much part of your identity: it’s who you worked really hard to become.’ He had always prided himself on supporting patients all the way through their hospital stays. So when he took planned retirement at 60, he did not consider working part time.

But he wanted a phased retirement, not a ‘crash landing’, and there were other interests he wanted to pursue. Chief among them is his longstanding role as an examiner for the Royal College of Surgeons FRCS: this involves working with trainee surgeons and colleagues and enables him to update his knowledge regularly.

‘I’m still very much in the world of surgery, not in the operating theatre but meeting with, learning from and sharing experiences with other surgeons,’ says Mr Singh.

‘A big part of being a consultant was the camaraderie and learning from each other. I feel that’s still available to me.’

SINGH: Supports doctors who are struggling

SINGH: Supports doctors who are struggling

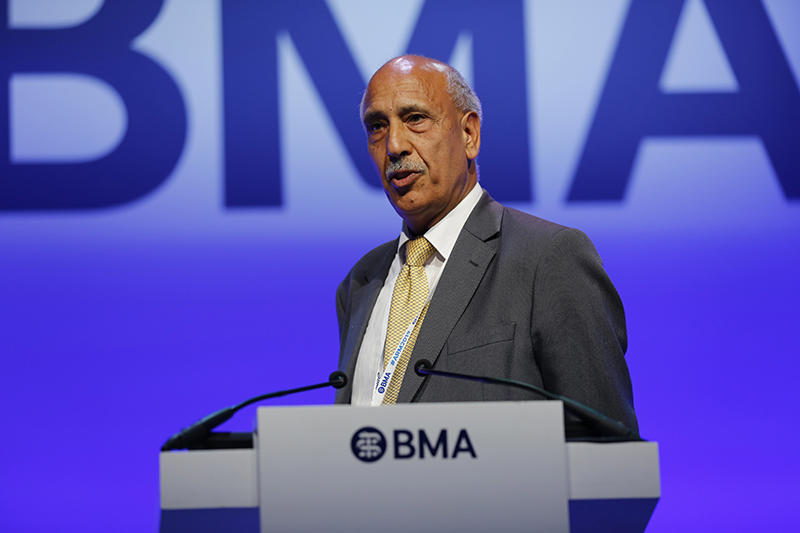

Since retirement, he’s also been busy as a member of the faculty at the Cambridge anastomosis course, working as a clinical supervisor at a COVID vaccination centre, serving as deputy chair of the BMA retired members conference, and even operating on hernias for a charity in Ghana.

One of his most fulfilling roles is volunteering with the BMA’s peer support scheme, mentoring struggling doctors and those undergoing GMC investigation. He is passionate about this work, believing it to be a potential solution to the NHS’s recruitment, morale and retention issues.

He has lobbied, through the BMA, for doctors to be given ‘protected time and space for confidential reflection, with a mentor of their choice’.

He hopes the NHS and GMC declare this ‘best practice’, to encourage employers to provide it as standard. ‘We’re almost 50,000 doctors short and the most experienced, the most knowledgeable are just being let go,’ says Mr Singh.

Untapped talent

The positive experiences retired doctors have in returning to work are often marred by frustration at red tape and technical hurdles.

Tom Kinloch retired from general practice on Merseyside in 2019, having worked for 34 years in the practice where his parents were GPs before him. He retired slightly early, partly because of pension taxes – but was keen to contribute and support former colleagues as the pandemic unfolded.

He was one of about 30,000 doctors who gained temporary emergency registration with the GMC in spring 2020, and NHS England suggested he applied to the CCAS (COVID Clinical Assessment Service). He did – and heard nothing further.

Ultimately, he secured work as a CCAS assessor through his own contacts, from his time as chair of the local medical committee. The same thing happened when he applied to support the COVID vaccination drive. Online applications disappeared into the ether.

It was through local NHS England contacts that he became lead GP at a local vaccination hub. He found both roles hugely rewarding – but the recruitment process deeply frustrating.

KINLOCH

KINLOCH

‘It was a national crisis, and the whole country was falling apart,’ says Dr Kinloch, a member of the BMA retired members committee.

‘Several colleagues readily volunteered as I did, but didn’t have the local contacts. Eventually they just gave up.’ In September, the temporary GMC registration given to doctors such as Dr Kinloch was extended till 2024. But, given that its original intention was ‘to support the response to the pandemic’, he’s not sure how he can help – and nor are NHS administrative staff he has spoken to.

‘There are things I could do to help my old practice – field some queries, medicine reviews perhaps – so they could concentrate on face-to-face contact with patients. But it is far from clear what we can offer or be asked to do. They need to tell us. If you have got the skills and there is a need, it feels a little as if there’s a moral obligation to get involved.'

(Main image courtesy of The Lancashire Telegraph)