Some people find politics. For others, politics finds them. It was 1992, and Chaand Nagpaul was hiding his nerves as best he could.

Recently qualified as a GP, he had no previous BMA experience, but there he was, about to deliver a speech to hundreds of doctors at a BMA annual representative meeting for the first time. He remembers the faces in the audience, ‘unfamiliar, politically savvy, opinionated’.

What had brought him there was his anger at the Conservative Government’s 1990 health reforms, which had introduced a purchaser-provider split and a competitive internal market in the NHS. He felt betrayed – that the very NHS values that drew him to become a doctor were being destroyed – and he wanted the BMA to challenge the Government head on.

His speech went down well, very well. He was completely unprepared for the ensuing standing ovation, the hordes of representatives coming up to thank him, and the media coverage that followed.

I simply wanted to shout from the rooftops about what I felt were such damaging reformsDr Nagpaul

This marked the beginning of his career in the BMA, becoming a regular speaker at ARMs, elected to the BMA GPs committee in 1996, after which he progressed in national representative roles in the association.

‘When I look back, my career in the BMA was very much by accident rather than by design. I simply wanted to shout from the rooftops about what I felt were such damaging reforms striking at the heart of the NHS’s founding principles.’

Dr Nagpaul has a conviction for equality driven by his own profound, visceral response to experiencing discrimination at an early age.

Born in Kenya to parents of Indian origin, his family moved to the UK in the late 1960s when he was seven years old, as part of the exodus of Asians from East Africa. He recalls feeling shocked and fearful at the open hostility to foreigners at the time, with racist signs in windows making it abundantly clear to anyone from an ethnic minority that a particular job or flat was not available to them.

He heard phrases such as ‘Paki-bashing’, reflecting the reality of racial assaults. He and his sister were the only non-white students at primary school in Finchley, north London.

‘I felt exceptionally alone and misunderstood,’ he says. Secondary school was a little more diverse, and had high standards.

‘I realised at a young age that to succeed in a society in which your colour disadvantages you, the one thing I could do was to work hard to excel academically. That would give me a secure future career.’

He was rewarded with offers from four London medical schools, of which Bart’s was the one he accepted.

‘Foreign-sounding name’

The reality that prejudice had not disappeared from British society hit him hard when, despite an impeccable CV, he received nine consecutive rejections without interview when applying for GP training schemes in 1986.

He sought advice from his trainer who felt the rejections probably related to his foreign-sounding name – a disturbing phenomenon also unearthed in celebrated research by Sam Everington and Aneez Esmail several years later.

For his 10th application, Dr Nagpaul presented himself in person at Charing Cross Hospital, knocked on the door of the postgraduate tutor, handed him his CV to put a face to his name, described his passion to become a GP, and urged to be considered for an interview.

He was thereafter shortlisted and offered one of two places out of 180 applicants. He recalls researching studiously for the interview, knowing more about the green paper reforms for general practice at the time than the senior GPs on the interviewing panel.

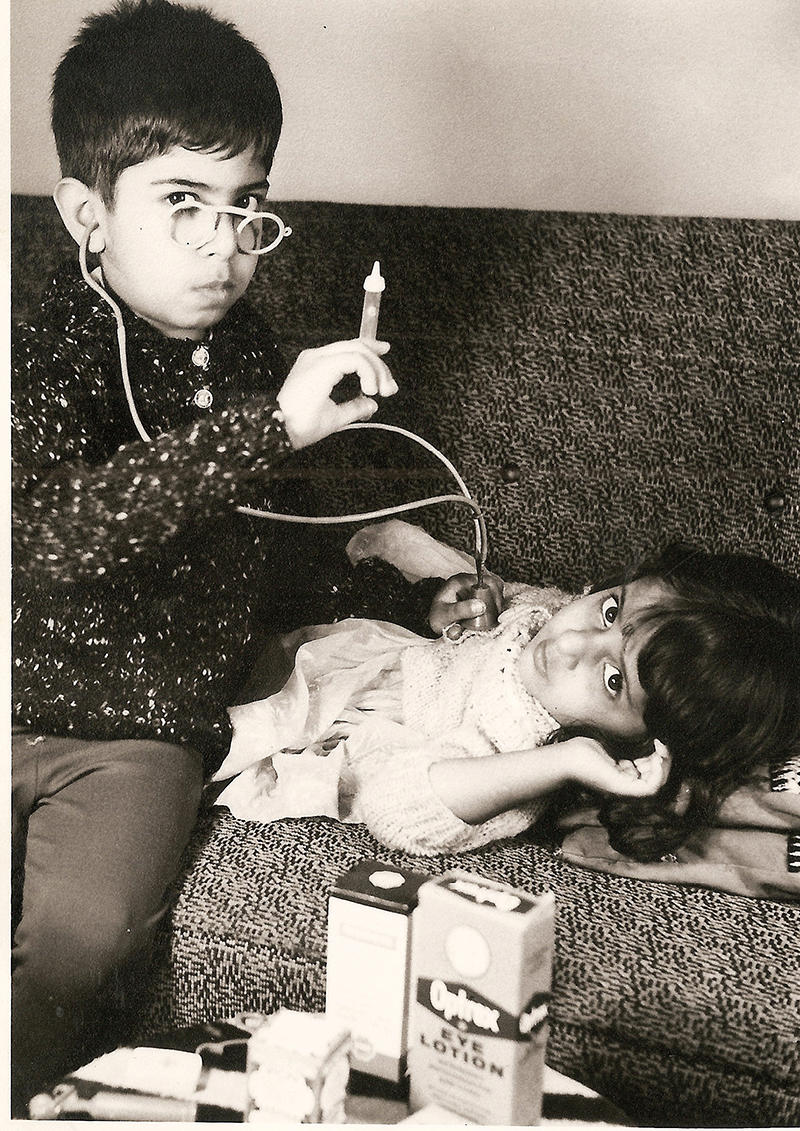

PRESCIENT: A young Chaand Nagpaul plays doctors with his sister Seema, who is also now a GP

PRESCIENT: A young Chaand Nagpaul plays doctors with his sister Seema, who is also now a GP

Here is another feature of Dr Nagpaul, noted by those who have worked with him throughout the decades at the BMA – he does his homework, and is in command of his brief. ‘Winging it’ may be good enough for certain prime ministers, but it’s not for him.

His ARM speeches were invariably fluent, urgent and precisely timed. ‘I used to cut out articles throughout the year. This was before the internet and I’d go to the local library to research my speeches, because I knew what I was saying had to have substance,’ he says.

He chose to become a GP during his general practice attachment in an inner-city London practice as a medical student.

‘I was overawed as I watched my GP tutor manage the entire spectrum of medical conditions and pathology, with dexterity and sensitivity. I also saw how patients deeply trusted their GPs, confiding in them with information they wouldn’t even share with their loved ones. From that moment I knew I wanted to be a GP.’

I saw how patients deeply trusted their GPs, confiding in them with information they wouldn’t share with loved onesDr Nagpaul

Dr Nagpaul became a partner in a group practice in Stanmore, north London, in 1989, the day after completing his GP training.

He has worked at the same practice since for 33 years, serving a large multi-ethnic community and he is passionate about the continuity of care he has been able to offer.

He has overseen the expansion of his practice to three times its original size, into a modern bespoke multi-professional medical centre. His conviction that GPs should be properly supported and resourced underpinned his election in 2007 as the first non-white member of the GPC executive team.

When he was thereafter elected as the first ethnic minority GPC chair in 2013, he inherited a contract imposed by the-then health secretary Jeremy Hunt, with punitive and unachievable demands such as some 100 per cent target achievements.

‘Relationships had broken down. I wrote to Jeremy Hunt asking for a meeting. My emphasis was on patient care, and I graphically explained how his imposed contract would actually harm patients, threaten trust between doctor and patient and in turn be damaging for government itself. It appears he listened, such that the majority of his imposed contract was reversed within six months,’ he says.

He also negotiated proper sickness and maternity leave reimbursement for all practice GPs, addressing practices being exposed to extortionate costs of cover. ‘I was putting right a wrong that had discriminated against practices with sick and pregnant doctors.’

He also led the Quality First workload management initiative for GPs, to address inappropriate workload afflicting GP practices, which included negotiating changes to the hospital contract in England to end GPs re-referring patients for missed outpatient appointments, or chasing secondary care-generated test results.

Breaking the glass ceiling

In 2017 he was elected as the association’s first ethnic minority council chair in its 190-year history. He couldn’t help but look back at his first years in the BMA with a predominantly white hierarchy.

Not in his wildest dreams could he have imagined ever becoming chair of its council. He felt that by breaking this glass ceiling he also was repaying the hopes and trust that many ethnic-minority doctors had invested in him, while demonstrating the BMA had come a long way in becoming a more diverse organisation.

Dr Nagpaul has always believed in thought leadership and as council chair led one of the BMA’s most ambitious projects, Caring, supportive, collaborative, underpinned by a comprehensive survey of 8,000 doctors’ experiences, together with feedback from grassroots members in roadshows he attended across the country.

Published in 2019, the report defines a vision of a health service driven by a culture of learning and support, with equity of opportunity and reward, an adequate workforce and collaboration between primary and secondary care.

He presented his proposals in roundtable talks at BMA House attended by senior figures including the-then health secretary Matt Hancock and NHS England chief executive Simon Stevens.

The findings have been quoted in publications of NHS England and the GMC, and have influenced policymakers from various stakeholders. Dr Nagpaul has publicly called for root-and-branch reform of GMC processes believing them to be disproportionate, flawed and unjust, with racial bias in which ethnic-minority doctors are referred at twice the rate to disciplinary hearings.

He also strongly believes GMC investigations must always hold accountable systemic root causes rather than doctors in isolation. On becoming chair of council, Dr Nagpaul could not have foreseen he would lead the profession through the once-in-a-generation crisis of the COVID pandemic.

His was a constant position of leadership and challenge, representing the profession through countless media appearances, at Parliamentary inquiries, and in meetings with ministers.

I had to speak out and challenge policies which I felt were likely to increase illness and deathDr Nagpaul

‘For me, this was not about political point scoring. My only purpose was to do right by the profession and safeguard the health of the population. I had to speak out and challenge policies which I felt were likely to increase illness and death,’ he says.

Tackling inequalities On every big call he was there, often well before the Government. He saw through ministers’ claims at the outset that there was sufficient personal protective equipment, speaking up for the thousands of doctors being put in harm’s way.

At the Health Select Committee in March 2020 he challenged the Government’s infection-control policies, which fell below World Health Organization standards, and which were subsequently revised by Public Health England.

He gave evidence to the National Audit Office about failings in Test and Trace, with private companies soaking up billions of pounds, to deliver an inferior service, after years of cuts to public health.

And while the Government tried on several occasions to ease social distancing prematurely, he held firm, even if it risked a backlash from libertarian critics. A prime example of this was in December 2020, when Dr Nagpaul pointed out the lack of sense in a planned five days of mixing during the Christmas break amid rocketing infection rates, only for the Government to bow to the inevitable at the last minute.

GRADUATION DAY: Dr Nagpaul with wife Meena, daughter Aneeshka, and son Rahul

GRADUATION DAY: Dr Nagpaul with wife Meena, daughter Aneeshka, and son Rahul

As council chair, Dr Nagpaul has demonstrably raised the profile of the BMA in championing ethnic-minority doctors and tackling race inequalities in medicine. In April 2020, he was the first medical figure in the media to call publicly on the Government to take action in response to the disproportionate effects of COVID on ethnic minorities.

‘It was alarming that the first 10 doctors who died of COVID – and almost 35 per cent of patients in intensive care at the time – were from ethnic minorities. I had to speak out.’

He subsequently wrote to every NHS trust in England to implement risk assessments to protect the most vulnerable doctors. He feels a deep sense of duty to support IMGs (international medical graduates) who he describes as the ‘migrant architects of the NHS’.

‘The NHS could not have survived without them. Over the decades they’ve taken on jobs with punishing rotas in hospitals that no one else would accept. GPs who worked in derelict, rundown premises serving their communities for decades. For me, they have been a source of immense inspiration, and the NHS owes them a deep debt of gratitude,’ he says.

Breaking down barriers

As chair of council, he set up an IMG champions group across all branches of practice, and led the creation of an international affiliate BMA membership to provide tailored support to IMGs while abroad, so they can be on the front foot before coming to the UK.

He also set up the BMA forum for racial and ethnic equality, which has increased engagement of thousands more ethnic-minority members. Recently, Dr Nagpaul oversaw the publication of the BMA’s landmark Racism in Medicine report, stating: ‘It reveals that racism is not only wrecking doctors’ lives, but also threatening patient care and services, with one third of ethnic-minority doctors having left or are considering leaving work, and 16 per cent off sick due to racist experiences.’

You cannot be unequal in your commitment to equalityDr Nagpaul

He is clear equality must apply to all diversity strands. ‘You cannot be unequal in your commitment to equality. It must apply to all characteristics from gender, sexual orientation to disability.’

He comments that the BMA has a network of elected women, and has recently launched the Disability, Long-term Conditions and Neurodiversity Network. His ‘helicopter’ view as council chair reinforced to him the interdependence of the entire medical profession.

‘We are one profession. You can’t sort out any one part of the system without sorting out the whole.’ He has long believed in breaking down barriers between primary and secondary care, quoting the Caring, supportive, collaborative finding that 60 per cent of doctors believe this is damaging patient care.

‘Doctors should be part of one team, on the same side caring for patients – not have a tug of war across a hospital-primary care divide,’ he says. And the BMA has to be there for all their needs.

To achieve this, Dr Nagpaul is proud of the BMA’s unique position as a professional association and trade union. Never was this more important than during the pandemic when, as well as seeking to protect members at work, he cites ‘medical ethics guiding us on mandatory vaccinations, our board of science informing us about the science of the virus and its impact on our members, while the international committee was instrumental in our calls for fair terms for IMGs coming to work in the UK’.

Dr Nagpaul came to the end of his term as BMA council chair in June, and was replaced by Philip Banfield. He is now devoting more time to his GP practice, where his wife Meena has been holding the fort as the lead managing partner.

‘The biggest price I paid in being BMA council chair, after losing time with my family, was the pain of not being in my practice. I was keeping my hand in by doing two surgeries weekly, but missing out on continuity of care with people I’ve known for so long – with patients asking me when I’m coming back.’

Watershed moment

He continues to chair the BMA forum for racial and ethnic equality and is a board member of the NHS Race and Health Observatory.

He is also vice-chair of his local medical committee, representing his colleagues at a local level, and he plans to take up a musical instrument – until now, a source of regret, because music got side-lined during his exceptionally studious youth.

His contribution and achievements on behalf of the profession have received due recognition. This includes a CBE for services to primary care, and multiple awards as being among the most influential figures in the NHS and among Asians in Britain. He was also recently awarded an Honorary Fellowship of the Faculty of Public Health.

Doctors should be part of one team, on the same side caring for patientsDr Nagpaul

Shortly after stepping down from his BMA role, Dr Nagpaul attended the graduation of his daughter Aneeshka from Liverpool University Medical School. So when asked about the future of the profession he has for so long represented, he cannot help but see it partly through her eyes, which reinforces the BMA’s call for adequate pay for junior doctors.

It has to get better, he says. ‘I do believe that we are at a watershed moment when the NHS just simply cannot continue the way it has. And I want Aneeshka, and the doctors of the future, to have a belief that they can be a part of a better future.’

Reflecting on his career, there is a remarkable consistency. He was affected and outraged by inequality from an early age, and a demonstrable commitment to tackling it continues to this day.

He began to represent doctors because he saw that the NHS was at risk of being fragmented and privatised, and still campaigns on these issues with equal passion.

And there has always been a desire on his behalf to bring the profession together, something he displayed with great success during the pandemic.

Dr Nagpaul is a huge fan of Bob Dylan, who once said: ‘People seldom do what they believe in.’ Dr Nagpaul is someone who very much has.