David Knight barely spoke a word to his dad as he drove him home for the last time from hospital.

He had been released for a bank holiday weekend, to his family home in St Austell, Cornwall – a three-and-a-half hour drive from the mental health hospital in Somerset where he had been placed.

Two days into his leave, David went missing. His mother immediately sensed something was wrong.

His father, brother and sister’s search of his usual haunts had all been in vain. Meanwhile, a train stood still on a viaduct, close to their home.

‘I stayed at home in case he phoned up,’ says David’s mother, Julie Nancarrow, in an interview with the BMA just over two years on from her son’s death.

‘It was just wait, wait, wait. I felt sick to my stomach because I knew. I knew there was something wrong. That train. I knew it was something to do with David.’

Unable to stop

David Knight

David Knight

An inquest into David’s death the following year recorded a verdict of suicide and the evidence it heard prompted an intervention from Cornwall senior coroner Emma Carlyon that reached all the way to the Department of Health.

David, aged 29, had walked on to the train tracks and stood in front of an oncoming train, the inquest heard. Despite using emergency brakes, the driver was unable to stop.

Cygnet Hospital Kewstoke in Somerset, where he had been a patient for eight weeks, is one of many private hospitals used by the NHS when it runs out of local mental health beds, an increasingly common occurrence. It is 150 miles from David’s home, a not untypical distance for these so-called OOA or ‘out-of-area’ beds.

That the bed was outside of Cornwall, senior psychiatrists told the inquest, was ‘very likely’ to have had a bearing on his death. Cygnet Kewstoke had not informed Cornwall’s community health team that David was on leave. There’d been ‘no communication’ at all; no plan or support in place to reduce the risk of David harming himself.

While ‘misjudgement about leave’ can happen anywhere, the psychiatrists said in evidence, the use of an OOA bed had ‘increased the risk of poor communication’. Cygnet Health Care, which runs the hospital, says it has ‘worked with local NHS partners to learn from this extremely sad case’.

David was not, by far, the only patient in an OOA bed that month, that year, nor this one.

Around the time of David’s death, Cornwall had up to 40 patients in such beds. That year, across England, almost 4,800 patients were admitted to them in 2015-16, figures released to the BMA under the Freedom of Information Act shows.

David’s case was raised with health secretary Jeremy Hunt and NHS England late last year by Dr Carlyon in a ‘report to prevent future deaths’ to flag the chance of tragedies occurring under similar circumstances.

She urged a review of bed numbers in Cornwall to end the ‘routine’ use of OOA admissions. ‘I understand though that this is a national issue,’ her report tells Mr Hunt.

No suitable beds

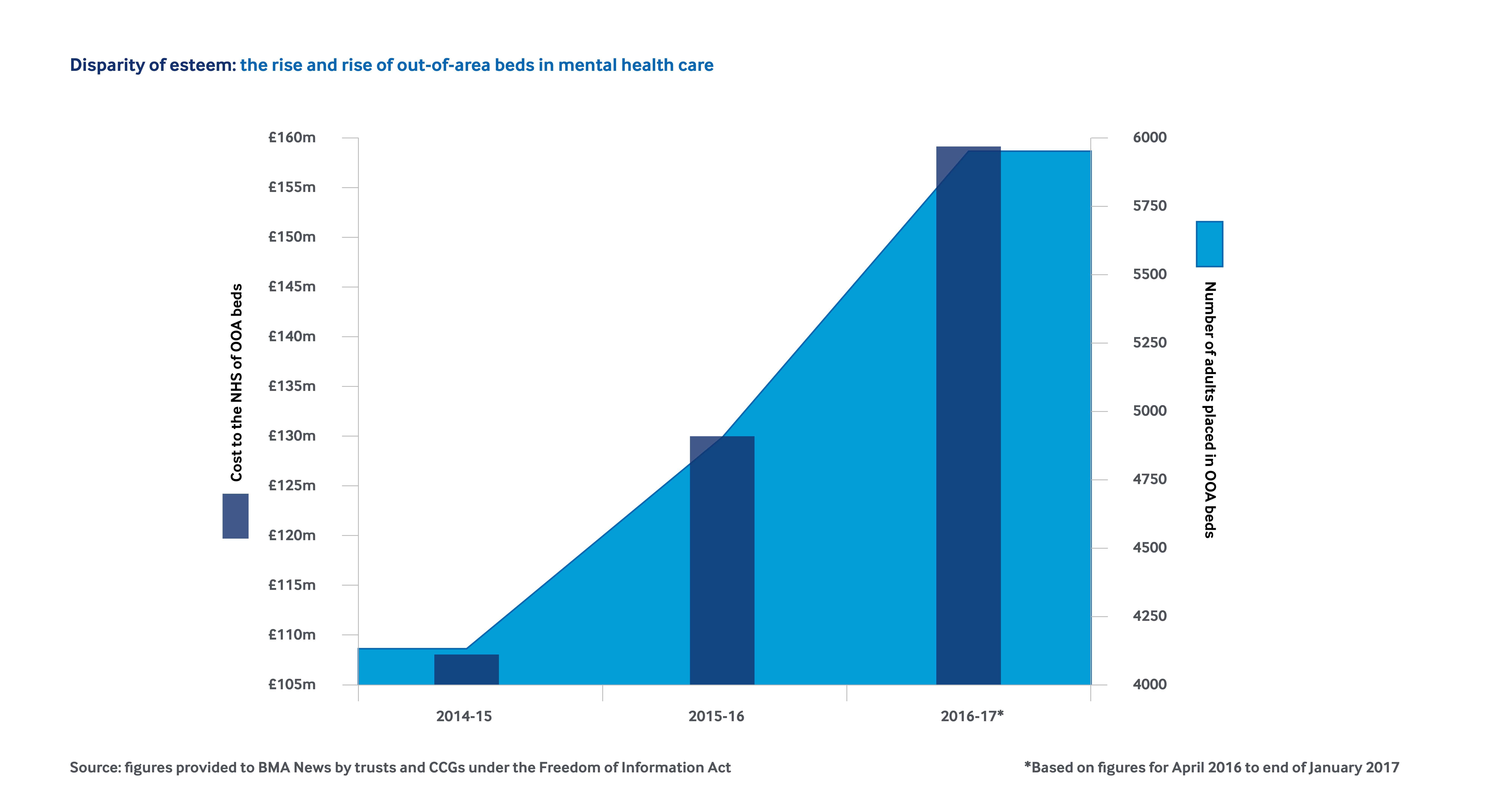

Despite the known risks of OOA beds, the numbers are going in the wrong direction, rising 40 per cent from 4,213 in 2014-15 to 5,876 last year, BMA research shows.

In some trusts, use has rocketed: seven-, three- and two-fold respectively in Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust; Oxleas NHS Foundation Trust, south London; and Mersey Care NHS Foundation Trust in the north-west.

More than half of the 44 trusts areas we examined, including Cornwall, admitted more than 100 patients to OOA beds last year.

In a few areas, the practice of dispatching patients with severe mental ill health has become the rule because the NHS has no suitable beds at all.

We’ve discovered that there are no PICU (psychiatric intensive care unit) beds for women in Barnet, Enfield, Haringey or Leicestershire, according to trusts and CCGs (clinical commissioning groups) in those areas. In Derbyshire and Derby City, there are no such beds for men or women.

‘There is a shortage of mental health beds nationally,’ a spokesperson for Derbyshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust says. ‘We are working with our commissioners to see what can be done to address this issue.’

The lack of PICU beds for women in Leicestershire has been raised with the health secretary in another report to prevent future deaths.

Leicester City and south Leicestershire assistant coroner Lydia Brown told Mr Hunt last year that ‘all female patients can only be placed out of area, potentially many miles away from home and local support'.

Her warning followed an inquest into the death of Victoria Halliday, who took her own life, aged 19, in 2015, while a patient of Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust. Leicestershire has seen the number of patients moved out of area rocket from 18, the year before Ms Halliday’s death, to 145 in 2016-17.

‘We recognise that it’s not ideal to send people away from home and family,’ a spokesperson says. ‘We have worked hard on an ongoing programme of improvements.’

East Leicestershire and Rutland CCG, which funds its mental health beds, is discussing ‘the possibility’ the trust ‘may resume’ offering PICU beds for women, it says.

On the hunt

Gerald Knight and Julie Nancarrow

Gerald Knight and Julie Nancarrow

BMA consultants committee psychiatric specialty lead Andrew Molodynski says it is ‘simply shocking’ that large parts of the NHS have no PICU beds. Doctors, nurses and social workers often spend hours hunting for OOA beds, Dr Molodynski says. ‘This hunt takes us away from other severely ill patients.’

OOA admissions have opened up a ‘safety gap’ in patient care, he adds. ‘Unfamiliar hospitals and staff lack the detailed knowledge of patients, held by their doctors back home; they’re less familiar with the risks patients pose to themselves and the treatments that have worked well in the past.’

As well as the risks posed to patients, families are commonly forced to travel long distances for visits, a BMA analysis of more than 1,100 patient journeys has found. On average, visits involve a four-hour drive in a day; a six-hour trip by public transport.

Many endure much longer journeys. Patients from Somerset and Derbyshire were admitted to beds in Scotland, last year. Trusts in Kent and north London, sent patients to Darlington. The Priory in Bristol, a private hospital, took NHS patients from north Essex, Lincolnshire and Leicestershire, to name but a few.

For David’s parents, a single visit involved a seven-hour roundtrip, on his father Gerald Knight’s one day off work a week, often giving them just an hour to see their son.

‘He felt safe with me or he felt safe in hospital, but when he was there, it was just a load of strangers,’ Ms Nancarrow says.

‘Coming from his home, where he stayed with his mum and dad and his family popping in, he had none of that. David asked us to stay a bit longer. He desperately wanted us to and we did. But it was such a long journey back. He was so far away, he just felt he was on his own.’

The Cornwall coroner wrote that David’s parents and his dog, Loki, a three-year old Alaskan Malamute, were ‘significant protective factors in preventing him from self-harm and recovery’, in her report, sent to Mr Hunt.

Lengthy journey times ‘made it difficult to physically and practically’ arrange leave and visits and impossible for Loki to be included in his treatment.

Ms Nancarrow says David loved his dog. ‘When he was making a fuss of Loki it was getting all the horrible things out of his head that was taking control,’ she adds. ‘He used to walk his dog 12 miles a day when he was feeling better. It used to give him a break from all the things that were going through his head.’

She traces the deterioration in her son’s mental health to the day he was hit in the face with a brick by an older boy when he was 15.

‘He was such a lovely baby, cheerful. As he got older, he was so happy,’ she says. ‘It was a good time until he was 15,’ Ms Nancarrow adds. ‘Then he became scared, wouldn’t go out on his own. He went downhill, downhill, downhill until he done what he did.’

David was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, which the coroner said was ‘exacerbated by non-compliance with prescription medication and cannabis use’, following the jury’s findings at the inquest. Ms Nancarrow doesn’t believe cannabis use contributed to his suicide.

Less supply, more demand

Mental health trusts gave a range of reasons for heavy and rising use of OOA beds, including budget and beds cuts and temporary ward closures, which allowed a culture of increasing dependency to creep in.

Barnet Enfield and Haringey Mental Health NHS Trust’s 151 per cent rise in use since 2014-15 is driven in part by an absence of female PICU and inpatient rehabilitation beds, a spokesperson says.

‘We strive our hardest to ensure we provide the best possible care,’ he adds. Growing financial pressure had left the trust with ‘the lowest bed base’ despite the ‘highest rate’ of people detained under the Mental Health Act in London.

South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust says a rise in expenditure on OOA beds from £3m to £8m between 2014-15 and 2015-16, was due to ‘bed reductions’ and ‘increased demand’.

Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, which doubled the number of such placements last year, hopes to improve by boosting support in the community and reducing delayed discharges.

All trusts told BMA News they had plans in place to reduce these admissions.

NHS Kernow CCG, which covers Cornwall, says it has developed an ‘action plan’ since David’s death ‘to ensure all services work together, including the police, council, acute trust, out of hours and our providers’.

‘We have also worked with Cornwall Partnership NHS Foundation Trust to agree an operational process should an out-of-county placement be required,’ he added.

Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust has seen a ‘huge reduction’ in its use of OOA beds since instigating a series of steps, its clinical director Rob Bale says.

Some were unavoidable, as patients needed highly specialist care or turned up for admission, miles away from home, he adds. ‘But we absolutely recognise that sending someone acutely unwell to a hospital miles away from home has a huge effect on their and their carers’ experience.’

Senior clinical staff from wards and community teams now jointly discuss patients and bed availability in daily telephone conference calls. ‘I know on a day-to-day basis what the bed situation is and where the pressures are,’ he adds. Reducing use required a ‘culture shift’ in Oxford he says.

‘When staff saw OOA placements being used, they all used them more and more. Now we’ve got things back on track.’

Ministers believe OOA placements can be eliminated ‘entirely’ in acute mental health by April 2021, according to their Five Year Forward View for Mental Health.

But there’s no national plan to reverse decades of decline in bed numbers.

Careless community

The Government and NHS England have spelled out their plans to tackle the increasing reliance on OOA placements in response letters to the coroners who heard David Knight’s and Ms Halliday’s inquests.

In a letter to Cornwall’s Dr Carlyon, NHS England national medical director Professor Sir Bruce Keogh said problems in accessing acute beds ‘are not just a reflection of the number’ but because of ‘inadequate community provision’ and disjointed working.

The then health minister Nicola Blackwood told the Leicestershire coroner, in her response, that decisions on PICU beds were down to the CCG.

Pressure on mental health beds were owing to ‘the lack of high-quality community care’ as a ‘viable alternative to hospital admission’ in some areas.

It said: ‘This has resulted in more people being admitted to hospital out of area,' adding that the Government had pledged an additional £400m to improve community care.

NHS England also last week unveiled a plan to test ‘new approaches’ to mental health services across 11 areas in England. Its first phase aims to cut the number of OOA placements by 283 across six other sites with no extra funding. It expects the pilots to pay for any extra services or local beds with the money they save.

Dr Molodynski says it is ‘naïve’ to think better community care will solve the issue of OOA beds. ‘Sometimes people just need to be somewhere safe for a bit.’

Our research findings and the ‘horror of human suffering’ caused by OOA beds should prompt a complete rethink of adult mental health policy to help stop and close the ‘care gap’ which is gaping evermore widely open, he says.

For Ms Nancarrow and Mr Knight, they hope some good might come from David’s death, even as they live with its reality every day.

As a taxi driver, his dad has a constant reminder in every fare picked up from the train station. His mum, in her handbag, carries a tasteless cutting from a local paper, showing her son’s body on the train tracks.

‘They had no right to do that, but it’s the last picture of David that I have,’ she says. ‘I think about him every day. If it would help any family, what I’ve been through, I’d do anything.’