There are evenings when Justin Varney looks out across the Birmingham skyline, below, and sees 1.2 million patients – their lives in his hands; the fates of their communities resting on his shoulders – and the burden of responsibility feels totally overwhelming.

Birmingham

Birmingham

Questions rattle around his mind: ‘Have I run out of ideas to stop the spread?’ ‘What else can I do?’

It hardly feels like the moment of rest or reflection needed after another 13-hour day which has seen 400 emails sent and scores of crucial decisions required – decisions only the director of public health in England’s second-largest city can make.

And it will likely only be a brief moment of peace. The work does not stop. There will be more phone calls and emails from political leaders and members of the community desperate for guidance and answers.

Bottle bank

‘Relentless’ barely covers the last 12 months for Dr Varney.

There have been moments of great personal pride: in March as stocks of hand sanitiser ran out across the country Dr Varney brought the city’s universities together to find any stocks of ingredients they had.

They bought hundreds of plastic bottles from a local homewares shop on his personal credit card, set up a bottling line manned by public health staff in the basement of the City Hall and distributed hand sanitiser to children’s care homes across Birmingham.

And Dr Varney’s team has also brought mosques and churches together to help communities and supported the growth of networks of foodbanks.

But, there has also been the abuse from COVID deniers, business owners angry about their fates, a constant feeling of being a local ‘arm of the secretary of state’ and those relentless 13-hour days.

The combined toll was such that in May, Dr Varney thought he had suffered a silent heart attack. In the face of his endless workload, he continued working for a week, regardless.

‘Like many doctors I ignored my symptoms for a while,’ Dr Varney tells The Doctor. ‘I was exhausted, I put off doing anything about shortness of breath, extreme fatigue and loss of exercise capacity. I didn’t have time to stop and look after myself, decisions had to be made.’

Unrelenting

Ultimately, Dr Varney’s illness turned out to be multiple diffuse bilateral pulmonary emboli across both lungs, probably as a result of asymptomatic COVID-19 infection.

‘I think the radiologist used the phrase “shotgun”,’ he says. Dr Varney’s anticoagulant treatment was planned overnight and began in the cracks in the next day’s work schedule.

‘It has been a rollercoaster,’ Dr Varney says, reflecting on the last 12 months.

‘It alternates between being exhausting, overwhelming, humbling and challenging. It has stretched me intellectually, physically and emotionally like nothing else.

'It has been an unrelenting series of demands with very little gratitude or acknowledgement.’

It is in these stark conditions that a whole profession has worked for the last 12 months.

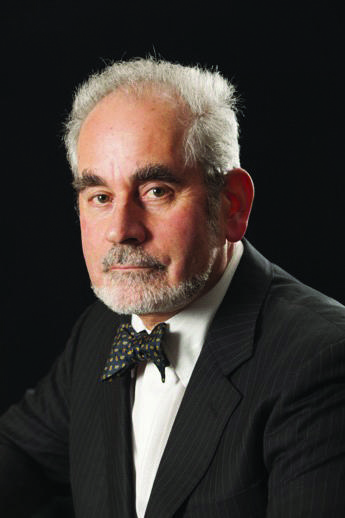

VARNEY: 'It's been a rollercoaster'

VARNEY: 'It's been a rollercoaster'

Last moments

Palliative care registrar Simon Tavabie was working in a hospice as the first wave of the pandemic hit – and in a busy London hospital during the ‘brutal’ second wave.

Dr Tavabie trained in his specialty to give understanding to patients during their final moments – to find out what matters to them and their families.

But there is precious little time for understanding in this tsunami of tragedy.

TAVABIE: Care to the end

TAVABIE: Care to the end

‘A lot of the nuanced palliative care I am used to providing just isn’t possible,’ Dr Tavabie says.

‘Last week we had as many deaths as we would expect in at least a month if not two normally.’

Seeing patients with oxygen levels of 50 or 60 per cent – ‘not compatible with life’ – and trying to comfort families who cannot understand how their relative, awake and talking is likely to die in the coming hours, is a daily occurrence.

Every 12-hour shift will live with these doctors ‘for a long time’, as Dr Tavabie says.

‘I think, when the dust settles, I am going to have a significant amount of emotions to have to deal with.’

Baptism of fire

Facing this amount of death is perhaps even more troubling for those at the beginning of their careers.

Albert Koomson was a final year medical student when the pandemic hit. His final exams were cancelled and he and colleagues were asked whether they would volunteer in hospitals already being stretched by COVID.

Dr Koomson moved from his medical school back home to Essex and took up the call to arms. He was placed on a general surgery ward full of elderly COVID patients.

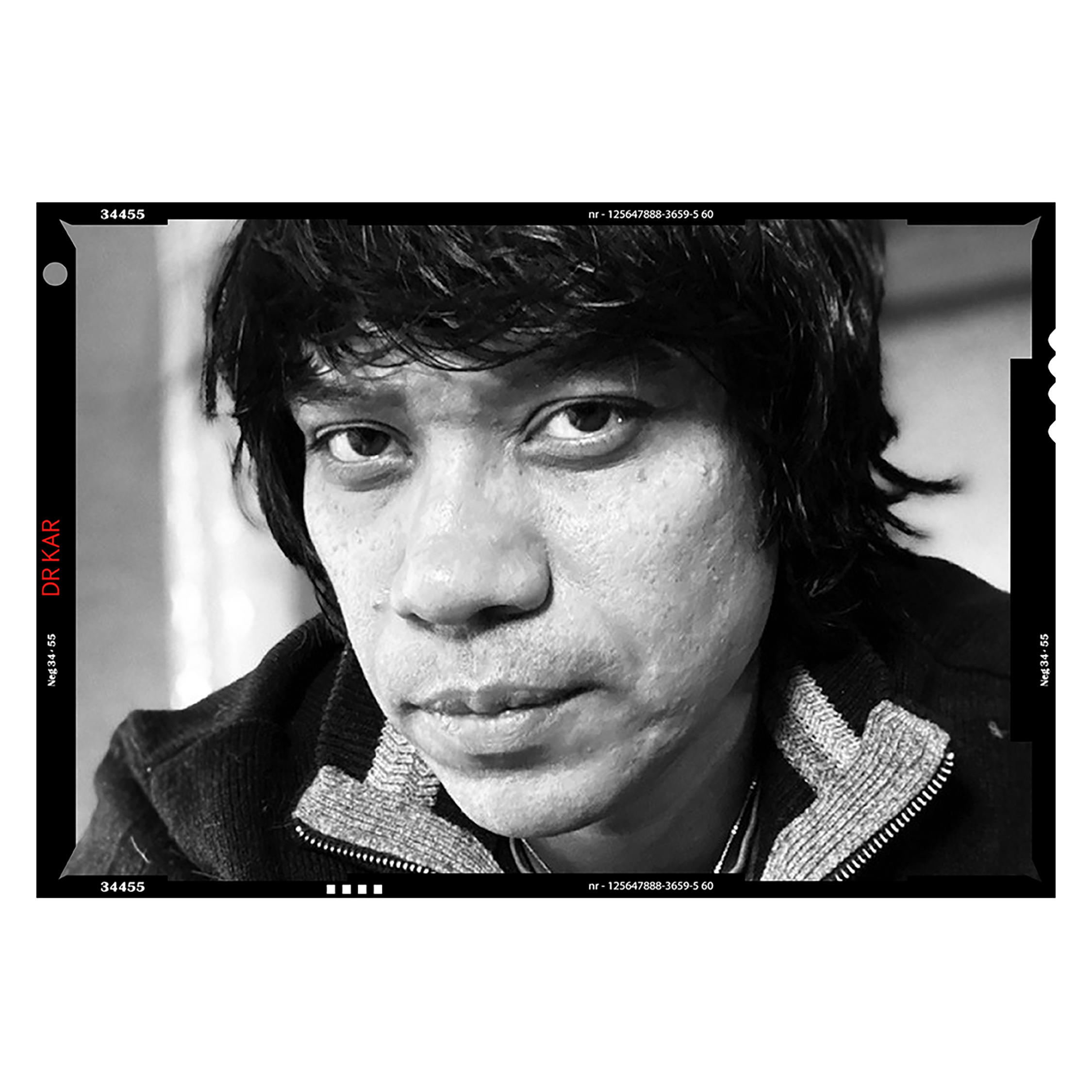

KOOMSON: Call to arms

KOOMSON: Call to arms

‘It will stick with me,’ says Dr Koomson. ‘It was quite overwhelming. Especially around Christmas time it was very noticeable that we were short on staff and we were just getting an influx of patients every day.

‘They were very elderly, had lots of co-morbidities and there was a lot of signing do not attempt CPR forms and a lot of discussions with families, preparing them for what was to come. I wasn’t really prepared to be that involved at such an early stage of my career, to be honest.’

We were getting an influx of patients every dayDr Koomson

DEANE: Emotional drain

DEANE: Emotional drain

Eleanor Deane, a final-year medical student in Sussex, who has volunteered for shifts in an intensive care unit, adds: ‘The main thing for me is that it is just one shift a week, whereas these nurses and doctors are doing those 12-hour shifts repeatedly, back-to-back. It must be such an emotional drain over and over again.’

There were 480 COVID-19 patients on the wards at an East Midlands teaching hospital in the final week of last month – higher numbers than at any point previously in the pandemic.

The sombre figures are accompanied by a note sent to staff from the medical director which reads: ‘We have already asked so much of you, but to get through this together, I’m afraid we need to ask more.’

The critical care units have reached 200 per cent of their normal capacity and yet more operations and treatments will need to be cancelled to enable staff to support the doctors and nurses working in intensive care and the other hospital wards now swamped with patients with this new virus.

Third wave

It may be easy for many to forget that behind these figures lie a place of work and care, in which critical care consultants Sarah Linford and Christine Watson, also deputy head of service for critical care, have been fighting to save the lives of deeply unwell patients for a year.

In this part of the country there have been more peaks than troughs. The influx of patients in January represents a third wave of this pandemic – following huge admissions in October and November.

CRITICAL CARE: Drs Watson (left) and Linford (right) outside Queen’s Medical Centre University Hospital, Nottingham

CRITICAL CARE: Drs Watson (left) and Linford (right) outside Queen’s Medical Centre University Hospital, Nottingham

Dr Watson and Dr Linford have found great comfort in the resourcefulness and dedication of colleagues and the support from their employer, but the pandemic has been exhausting.

‘The difficulty is the length of time it has gone on for,’ Dr Watson says.

‘We see the sickest 10 to 15 per cent of the COVID workload. It’s a sense of relentlessness. Across the team, in essence, we have been running what amounts to more or less a major incident for almost a year with these numbers of patients. It has a massive knock-on impact for our health, sleep and wellbeing.’

Tough decisions

For Dr Linford, one feeling overrides everything else – the sheer ‘relief’ at having, so far, not been forced to make decisions like choosing one patient’s care over another’s, as was a very present fear during the early days of the pandemic.

‘I would dread having to make those decisions,’ she says.

Dr Watson, as clinical lead, was among those in charge of drawing up the worst-case scenario plans in those frightening, uncertain, early days and marshalling resources to build a system which could cope with the coming avalanche.

In March scenes from Italian hospitals filled the news – with doctors speaking out about having to ration care to patients, temporary morgues being built, and hospitals absolutely overrun.

‘We talked about it,’ she says. ‘If we didn’t it would have been irresponsible. But we were very clear at the beginning – and thank god we’ve been able to achieve it – that we would take each case on its merit and offer ICU to every patient that would benefit from it. Having to make those decisions would have been anathema to us.’

Through the cracks

Dr Watson and her team turned elective theatres into ICU capacity and worked out how to staff them. Like everywhere else across the country that, ultimately, means an end to the one-to-one intensive care, one specialist nurse per patient, that is usually seen on these wards.

‘If we didn’t need these ratios, we wouldn’t have them,’ Dr Watson says. ‘The vast majority of intensive care is about that attention to detail. As soon as you start to derogate from that things fall through the cracks.’

The impact of this unprecedented year of pressure has been keenly felt. Dr Linford says: ‘There are always patients that impact you more than others – there have been times when I’ve woken up in the middle of the night thinking about patients before.

'But the scale of it with COVID has been so much bigger. We’ve never had this number of people in our beds. Inevitably you bring more of that home and it has a knock-on effect on family life.’

'Exhausted'

The Doctor has spoken to intensive care staff in regions across England and the scale of the effects this pandemic is having on the workforce is marked by how unanimously difficult experiences have been everywhere.

Jagtar Pooni, an intensive care consultant in the West Midlands, speaks to The Doctor in short bursts broken by relentless calls from colleagues asking for help and advice.

‘They are exhausted and emotional,’ Dr Pooni says, when asked about the staff he works alongside. ‘They see this as going on for longer and longer and the light at the end of the tunnel is much further away.’

In recent weeks patients have become younger and more unwell.

POONI: Staff are exhausted

POONI: Staff are exhausted

Dr Pooni says: ‘The mortality seems to be higher. And in this surge there is a younger age group affected. Before we were looking at people aged 60-80 but there’s more in their 40s or 50s and some younger.

‘We look at them and think their health is relatively good, they are active individuals, they have families and jobs and fully participate in society. You look at them and think you are much closer to them in terms of age, health and personal circumstances. It does shock you.’

True picture

These are experiences that Kevin Fong, a London anaesthetist, who was seconded as national clinical adviser to NHS England’s emergency preparedness resilience and response team for COVID-19, has been trying to feed into senior leaders to close the gap between ‘data’ and the working lives of doctors facing this disease.

Professor Fong has spent time visiting and working in intensive care units during their busiest period and taking part in road and helicopter transfers of COVID-19 patients to understand and feel the fear that the frontline staff feel.

‘You have to, in order to appreciate what it is that frontline people are doing,’ he says. ‘It’s such a big incident and it’s hard to capture in any meaningful way in numbers alone. It’s about making sure the people out there actually doing the job have some sort of representation in the information that is passed on and the decisions that are made.’

FONG: 'It’s hard to capture in numbers alone'

FONG: 'It’s hard to capture in numbers alone'

Moral distress

While there is little doubt Professor Fong’s work is crucial and has a positive effect for staff on the front line, he cannot help but feel some guilt about having been away from the ‘shop floor’ while friends and colleagues were finding life so tough during the first wave.

‘You can hear the struggle in their voices, and you see it when you go down and see it yourself,’ he says.

You can hear the struggle in their voicesDr Fong

Julian Bion, freedom to speak up guardian at one of the West Midlands hospital trusts, told The Doctor that staff have faced numerous challenges during the pandemic – from the sheer pressure of demand, to facing difficulties communicating with patients through personal protective equipment, being unable to build supportive relationships with families, fearing taking the disease home to their families, and fears for their own health.

Weary doctors

He says: ‘The physical demands are considerable but there are also multiple sources of moral distress made worse by lockdown preventing the usual forms of mutual comfort and support.’

Professor Bion, who has retired from frontline clinical practice, adds: ‘My experience is vicarious – through what I see in my colleagues’ eyes and hear in their voices when I go into the ICU. I see the weariness and the fact that at times people are close to tears.’

The professor of intensive care medicine at the University of Birmingham, adds: ‘The problem is the health service may very rapidly forget the emotional burdens of the pandemic on staff, and as soon as the numbers go down we will get told to get on with the waiting lists. This is understandable but there has got to be time for staff to decompress.’

In hospital wards across the country – not least intensive care wards – doctors from a wide variety of backgrounds, levels of experience and specialties have volunteered to fill shifts totally alien to their normal roles. For some it has been an eye-opening experience, for others it has been exhilarating, and for many, reflection on these long shifts has been marked by overwhelming sadness.

BION: Colleagues close to tears

BION: Colleagues close to tears

Filling nursing shifts

In January, as a relentless storm of COVID infections and hospital admissions strangled London’s hospitals, consultant cardiologist Richard Schilling took on responsibility – along with a team of others – for arranging doctors to fill shifts taking on nursing duties. In the space of just two weeks 766 nursing shifts were filled – including by Professor Schilling himself.

‘I am used to being the top dog and very confident in what I do,’ Professor Schilling says. ‘You walk into an area where you can’t do anything that useful and you have to learn as quickly as you can. You can’t afford to be proud. It is a very humbling experience.’

The pandemic has been a period of great change for Professor Schilling, who was also one of the key figures in the establishment of the London Nightingale hospital.

SCHILLING: 'Can't afford to be proud'

SCHILLING: 'Can't afford to be proud'

Taking shifts on ICU has been more ‘exhausting’ than refreshing but equally valuable as London’s hospitals struggle under enormous pressure. ‘Working in this environment is brilliant because it self-selects people who are doers and went into medicine to help people and are willing to make sacrifices.’

He says: ‘The first wave it was all adrenaline and buzz – we all felt we were marching to war and understood what we were doing. It was an amazing, positive, energetic atmosphere.

‘But now these guys have been doing this constantly for a year and they are wiped out. I don’t know how they keep trudging to work and doing it. It’s a real grind. From me personally there’s a feeling of exhaustion and just sadness really.’

You walk into an area where you can’t do anything that useful and you have to learn as quickly as you canProfessor Schilling

'Bloody hell'

Malcolm Finlay is a consultant cardiologist and has filled some of those 766 shifts Professor Schilling and his team organised.

He says: ‘I sat on the Tube coming back one morning – sitting opposite my clinical director who had been doing the same shift.

‘We both said we just really don’t want to go back. It’s hard work, it’s emotionally draining – you look after a pregnant, 30-year-old who is ventilated and you just think “bloody hell”.

‘These are not the sorts of things you normally see in medicine – you might have one or two cases a year where you think “my god that is awful” but now you are in a ward and you see a chap down the way whose father, mother and brother all died in the same unit in the last four weeks.’

FINLAY: Emotionally draining

FINLAY: Emotionally draining

These are not the sorts of things you normally see in medicineDr Finlay

Early discharge

For Dr Finlay, as with many other people The Doctor has spoken to, there have been positives among the challenges, including the sense of ‘unity and purpose’, the sacrifices made by so many doctors to help out, the challenging of ‘snobbery and hierarchies’ and the insight into the work of intensive care nursing staff.

Dr Finlay describes those experiences as ‘humbling’ and ‘quite incredible’.

The impact on wellbeing and family life stretches beyond hospital wards and public health and across the profession.

In general practice, doctors have undergone great change and strain – innovating virtual and telemedicine, managing massive cohorts of patients unable to be seen in hospital and continuing to bear the risk of seeing the most needy face-to-face.

York GP Abbie Brooks says: ‘As GPs we are holding more risk because patients aren’t going into hospital, they are being discharged early and these are our risks to carry.

‘I was feeling like if my kids or husband got unwell, I was the person who brought it home. Even when we’ve been allowed to see people I’ve chosen not to because I don’t want to be that person.’

BROOKS: Early discharge risks

BROOKS: Early discharge risks

We both said we just really don’t want to go back. It’s hard work, it’s emotionally drainingDr Finlay

London GP Farzana Hussein agrees. She says: ‘At the moment I am really living on adrenaline. I am trying to look after two teenagers who have had A-levels and GCSEs cancelled.

'I have to say it feels like 12 years (rather than 12 months) – I have been working in the day and then in the evening. We have had to learn about this new disease, how to protect staff and as a single-handed GP I’ve had to be on top of so many things. I haven’t stopped since March.’

The question on many lips is what will we be left with after this pandemic is eventually behind us. It is a question regarding the economy and wider society – but not least the NHS and its exhausted workforce. The experiences of doctors on the front line are a recipe for PTSD and other mental health difficulties, burnout and an exodus to other countries or careers.

HUSSEIN: Learning about new disease

HUSSEIN: Learning about new disease

At the moment I am really living on adrenalineDr Hussein

Stressed out

Professor Fong co-authored a study published last month which found that nearly half of ICU staff are likely to meet the threshold for PTSD, severe anxiety or problem drinking during the COVID-19 pandemic.

He says: ‘There is definite injury – our staff are definitely injured and injured to a degree which impairs their ability to deliver care. Our duty of care extends to our colleagues not just patients because looking after colleagues is looking after patients.’

Asked what should be done to deal with this injury, Professor Fong is unequivocal. The end of the pandemic must not mark an immediate move to tackling waiting lists and diverting staff from one crisis to another. ‘We need a huge programme of rest and recovery – if not reward too,’ he says.

‘I think the stress that the frontline workforce has been under is unlike anything – possibly unlike anything outside of war. We need to do some deep thinking because to get this wrong will be to risk further injury and to risk retention of staff. This has been horrific.

‘It is really important to understand this is not a question of looking after staff or looking after patients. It is looking after staff so they can look after patients.’

NAGPAUL: Staff sacrifice must be recognised

NAGPAUL: Staff sacrifice must be recognised

BMA council chair Chaand Nagpaul says: ‘Doctors and other healthcare staff have made enormous sacrifices since the beginning of this pandemic. These past 12 months have stretched the emotional and physical well-being of my colleagues beyond comprehension.

‘Many of us will need time and space to reflect and recover when the worst of COVID-19 is behind us and it will be vital Government and NHS leaders show the leadership required to ensure this is possible.

'It will also be crucial that the sacrifices of staff are recognised with fair pay, better working conditions, more supportive, safer environments and, ultimately, that they return to normal work in an NHS which is properly funded and resourced.

‘The Government can no longer try to run our NHS on the goodwill of staff who have been asked to go above and beyond for far too long’.

Sacrifice and leadership

Like many others, Dr Varney has been through so much over the last 12 months. The personal triumphs against adversity, the great challenge and the endless days, the abuse and the health scares.

The unrelenting nature of this ruthless pandemic has been met and matched only by the unrelenting dedication, care and compassion of doctors and other healthcare staff who have put themselves at the greatest risk while protecting the public and saving lives.

On the spot: frontline doctors share their experiences

Partha Kar, diabetes consultant

‘It’s been a steep learning curve learning about the new drugs, when to intervene, calling for help, when to escalate for ICU and a lot of work has been supporting junior doctors, some of whom have been really scared when dealing with really sick COVID patients.

It’s been fascinating to see the NHS spirit – we have dermatologists and rheumatologists and people who haven’t done general medicine for 20 years and are happy to pitch in and be a foundation year 1 or an F2 on the surgical and orthopaedic wards.’

Charlotte Manisty, academic cardiologist

Dr Manisty volunteered in a London ICU and has been running an academic project looking at mild COVID among hospital staff.

‘It’s the teamwork that has been particularly impressive – everyone has been trying their hardest and recognising that ITU teams have been doing an incredible job under alarming pressure and we all feel we have to do our bit.

The NHS should be held up as an example of flexibility and teamwork and collaboration to try and cope in a pandemic situation but I think the under-resourcing of certain areas of the NHS has been highlighted.’

Danny Wong, anaesthetic registrar

‘I think there will be a lot of people who, because of the intensity of this, will have symptoms that could be similar to PTSD. People are being asked to do things that they haven’t had training for – especially some of the more junior doctors redeployed to ICUs who haven’t been on intensive care before let alone having to deal with a COVID ICU which is a completely different beast.

There is disempowerment and a feeling that you are meant to be in training but aren’t receiving that. I do worry it may make people leave.’

Martin McKee, member of the Independent Sage group

‘I don’t think I’d appreciated the volume of work that goes into it. We’re trying to inform public policy – I don’t think we should be so presumptuous to think we could influence it. Public policy in this country is particularly impermeable for the academic community.

There is a very clear view in the Government that scientists advise and policy makers decide. There are a lot of things wrong in the academics/politics interface in the UK and that has been a problem for years – that doesn’t make our life easy. The UK is one of the most difficult to work in, in terms of getting evidence in policy.’