For most doctors, retirement spells the end of 16-hour days and sleepless nights. But Jeremy Lockwood has never been busier than since he left general practice and reinvented himself.

Today, he can be found scouring beaches on the Isle of Wight for fossils, sorting through boxes of bones at the Natural History Museum, or writing highly technical pieces about iguanodons.

Because Dr Lockwood is a now a student palaeontologist, and a good one at that. Last year alone, he helped identify three new dinosaur species, rewriting dinosaur history on the island.

It’s this passion and his PhD that keep him awake till the small hours now. ‘I don’t play golf and I don’t like gardening much,’ says Dr Lockwood, ‘and if I’m left to my research, I just keep going. It can get a bit obsessive’.

A childhood passion

Dr Lockwood traces his interest in palaeontology back to childhood, when he spent days hunting for fossilised marine organisms such as trilobites and brachiopods in a local stream.

Study and medicine supplanted that hobby for years: Dr Lockwood was a GP at a practice in Burton-on-Trent for 28 years. But the sight of dinosaur footprint casts on a beach in West Wight rekindled his excitement and the island became a regular destination for Lockwood family holidays.

In 2015, at the age of 57, he decided to call it a day. ‘I loved my job but what made the decision for me was the Care Quality Commission coming in, another tier of scrutiny and stress.

'I wanted to open a new chapter in my life, while I was still young enough.’

By the start of the pandemic, he and his wife Patricia had already moved down to the Isle of Wight and he had started his PhD at Portsmouth University, studying iguanodons on the island. He volunteered his services to the NHS, re-registering with the GMC – but was considered to have been out of medicine for too long.

Hunters and hell herons

He was on the beach near Brighstone when a fellow fossil-hunter found a dinosaur snout, complete with teeth.

‘As we scouted around the beach, we both found other bits of bone, presumably the same animal.

Then, the next week, he found a second snout. Normally these finds are incredibly rare, maybe one in 100 years.’

Dr Lockwood was part of the team that found, named and identified those two spinosaurid, fish-eating dinosaurs last year: Ceratosuchops inferodios which rejoices in the name ‘horned crocodile-faced hell heron’, and Riparovenator milnerae or ‘Milner’s riverbank hunter’.

His other discovery came in a far less promising setting: basement storage units at the island’s Dinosaur Isle museum in Sandown and the Natural History Museum in London.

Spinosaurid skull model by Andrew Cocks

Spinosaurid skull model by Andrew Cocks

‘It was lockdown and I couldn’t travel so I thought I could document and measure all these bone fragments. It is rather tedious but I am quite meticulous and it helped me learn the anatomy in detail, so I could start to recognise variations.’

It was when he pieced together an iguanodon skull from fragments that he reconstructed a bulbous nose unlike any seen before. He concluded this nose belonged to a new animal; his supervisors, Professor Dave Martill from Portsmouth University and Dr Susannah Maidment from the Natural History Museum, agreed.

A peer review of his paper confirmed he had found a new species of iguanodontian and it was formally named Brighstoneus simmondsi in November, after Keith Simmonds who unearthed the skeleton in Brighstone in 1978.

New species, new insights

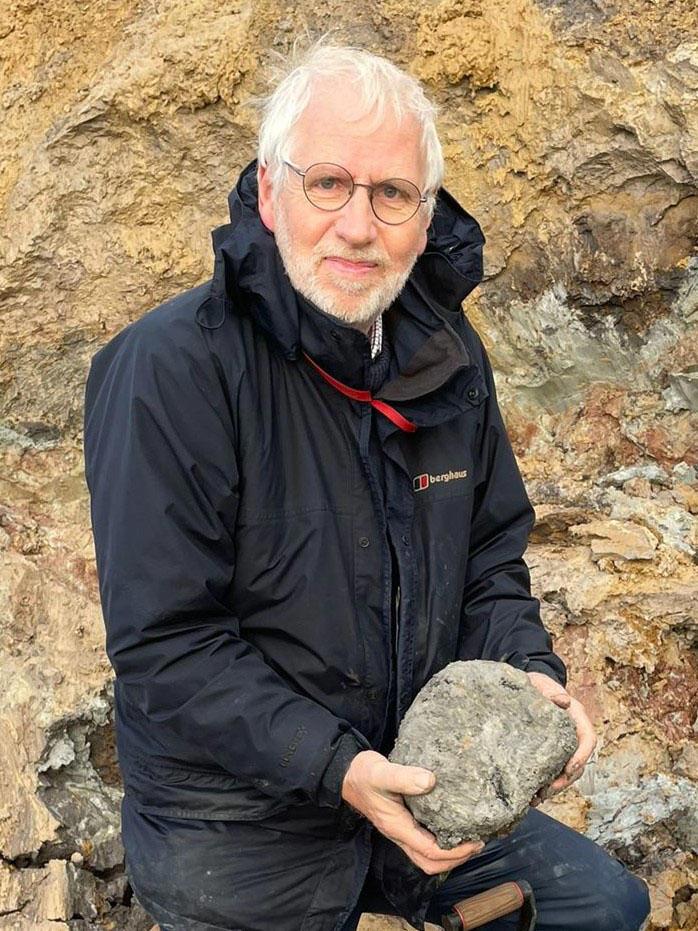

FOSSIL FIND: Dr Lockwood with a cervical vertebra

FOSSIL FIND: Dr Lockwood with a cervical vertebra

The discovery debunked the prevailing wisdom that there had been only two iguanodon-like dinosaur species on the island in the Early Cretaceous period (125 million years ago): Iguanodon bernissartensis and Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis.

It suggested in fact that there may be far more iguanodontian dinosaur species in the UK as a whole during the Early Cretaceous period than previously thought.

His discoveries also raise the status of the Isle of Wight as an exceptional place for dinosaur discovery. In the Early Cretaceous period, the Isle of Wight was a floodplain where major flood events offered the unusual conditions necessary for animals to be buried immediately after their death.

These days, coastal erosion eats into island cliffs at the rate of about two metres a year, revealing the fossils. Dr Lockwood is now coordinating a bid to redevelop Dinosaur Isle into a major museum and research centre, after the local council invited tenders.

A charitable group he chairs and a German company are collaborating on a bid. ‘We’re every bit as much a World Heritage Site as the Jurassic Coast and, with these new discoveries, it’s now dawning on people that there’s something really exciting here.’

He predicts more excitement this year. At low tide, he ventures out in search of more pieces of his current puzzle: a sauropod. He has already found a three-foot-long limb bone and is hoping the cliffs will yield more treasures soon.

A medical eye

Dr Lockwood recognises that his medical training – and his attention to detail – make him well suited to palaeontology.

‘Both medicine and palaeontology are about problem-solving. In medicine, you’ve got to elicit the history, get the facts, do other tests, and then try and work out what’s going on. Palaeontology on the Isle of Wight is like solving a jigsaw puzzle with bits missing and bits mixed together from different puzzles.’

His experience in fields such as histology and pathology mean he has started giving tutorials to other students in Portsmouth’s palaeontology department.

‘I’ve found quite nasty fractures in some bones, and possibly tumours,’ says Dr Lockwood. ‘We’re currently studying a dinosaur that might have had osteomyelitis.’

Some of the encouragement he has treasured most has come from former colleagues and medics: several say they have enjoyed his window on ‘life after medicine’. ‘The museum’s always looking for volunteers,’ he says.