It sounds like science fiction or an echo of a past horror. People rounded up into prison camps, their healthy organs removed without proper consent by unscrupulous surgeons for transplantation, all under a veil of state secrecy.

Yet, this isn’t fiction, according to many doctors, scholars, and campaigners. They say it’s been routine practice in China for decades and still is, a claim its government denies and the CMA (Chinese Medical Association) calls ‘groundless’.

So, what is fact and fiction in this alleged atrocity? To find out The Doctor has examined the evidence and spoken to doctors and scholars involved, from both sides of the divide of this highly contentious issue.

China has admitted much: that executed convicted criminals were its prime source of organs in tens of thousands of transplant operations through the 1980s, 1990s, and the early part of this century. It claims, however, to have banned this unethical practice in 2015 and relies now only on voluntary donations. Autonomous informed consent, that fundamental principle of medical ethics, cannot be obtained from people in the coercive environment of prison (see box, The medical ethics of organ donation).

Decades of relying on this readily available ‘source’ of death-row prisoners did, however, fuel a roaring commercial trade in transplant surgery in the pre-ban boom-time – including ‘transplant tourism’ – which it is struggling to stamp out. Hundreds of unregulated hospitals established themselves as transplant centres during that growth period.

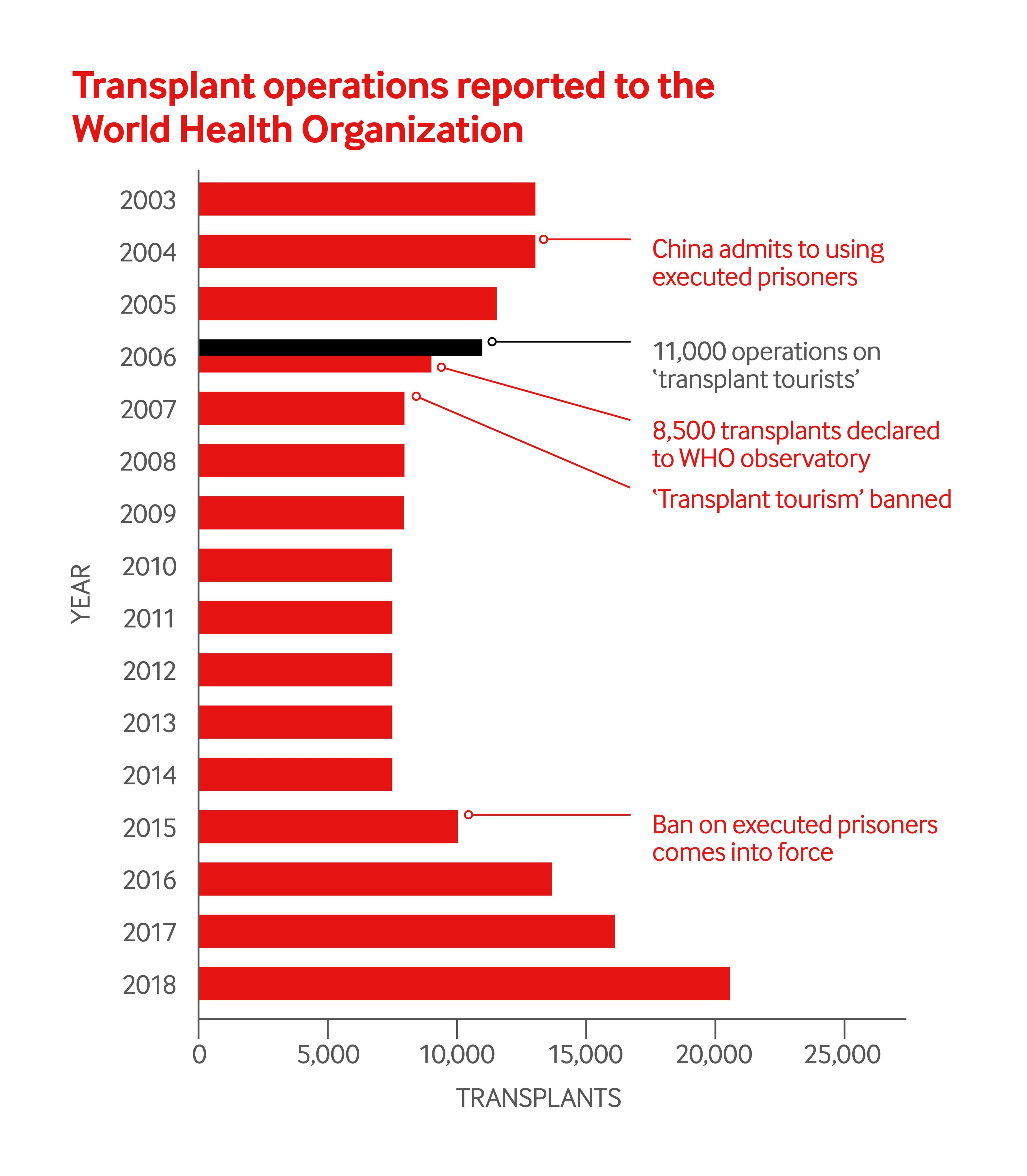

At its tail, in 2006, a year before transplant tourism was ‘outlawed’, 11,000 foreign patients had transplants in China. So said Francis Delmonico, a World Health Organization adviser, to a US House of Representatives committee a decade later. Executed prisoners would have been the principal source.

China’s doctors say voluntary donation is now the sole legal source of organs post-2015. Transplant centres must also be registered. Some 170 are, they say, a huge drop from the 600 previously operating, according to a 2015 paper in the Chinese Medical Journal. A few of the major centres have been visited by senior doctors from outside China – but only to help its healthcare professionals to improve practice (see graphic below).

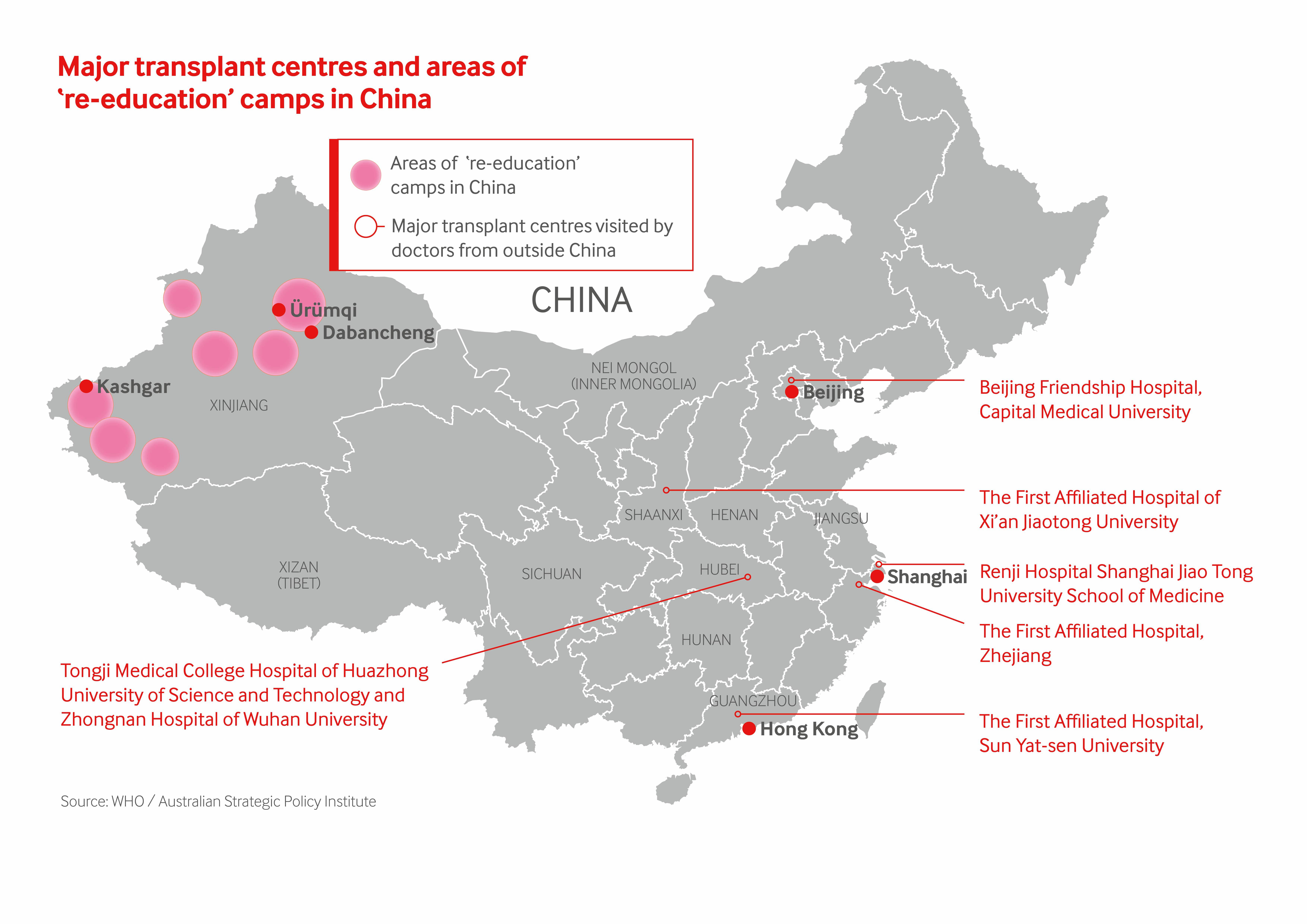

Major transplant centres and areas of ‘re-education’ camps in China

Major transplant centres and areas of ‘re-education’ camps in China

A national IT system now allocates organs in line with ‘internationally recognised principles’.

Greater transparency is promised for a ‘new historic stage’. Annual reports will be published in Chinese and English, says the first one from December 2019, seen by The Doctor. This admits to continued problems with illegal ‘organ trade gangs’ and the need for a ‘crackdown’ but says ‘hostile forces’ are ‘spreading rumours’ their progress is being ‘dismissed’.

Harvest claims

China has, however, repeatedly denied another serious but related charge: that it has and continues to ‘harvest’ organs by forcibly removing them from oppressed ‘prisoners of conscience’.

This ‘source’ has also been linked by doctors and investigators to ‘transplant tourism’.

It includes followers of Falun Gong, an illegal belief system in China, described as a ‘cancer’ by its embassies, and Uighurs, a largely Muslim ethnic minority, a million of whom are believed to be held in prison camps in Xinjiang, a remote province. Conditions in China’s ‘penal institutions’ for political prisoners are described as ‘harsh and often life threatening and degrading’, in the US State Department’s 2019 report on human rights practice published last month.

Despite China’s denials, allegations of ‘organ harvesting’ from prisoners of conscience are taken seriously by politicians, campaign groups, and medical institutions, including the BMA, the American Medical Association, and the World Medical Association to which they belong.

They’ve been probed by powerful politicians abroad, including a US House of Representatives committee on foreign affairs in 2016 and Australia’s equivalent in 2018. Hundreds of thousands of organs had already been ‘harvested’ from prisoners of conscience, the United Nations Human Rights Council was told last year.

Gross violation

BMA medical ethics committee chair John Chisholm last year described ‘forced organ harvesting’ as a ‘gross and continuing violation of inalienable, fundamental human rights’. He was speaking in June after the final judgment of the Independent Tribunal into Forced Organ Harvesting from Prisoners of Conscience in China.

This ‘people’s tribunal’, a kind of unofficial jury, was established by the International Coalition to End Transplant Abuse in China, an advocacy group. It concluded last year that ‘organ harvesting’ had been practised on ‘very substantial numbers’ of prisoners of conscience.

MEC member Baroness Ilora Finlay told the UK House of Lords last October that ‘extensive evidence’ in its judgment made ‘harrowing reading’.

‘Is it possible that some doctors could perpetrate such crimes against humanity?’

The tribunal’s full evidence file, released last month, runs to hundreds of pages. Much relates to events before the 2015 ban on the use of executed prisoners.

It does, however, include some more recent evidence to support the tribunal’s claims that organ ‘harvesting’ continues in China and that its victims include prisoners of conscience. This more recent evidence also casts doubts on China’s claim to greater transparency.

One of the tribunal’s most controversial allegations – which Chinese doctors deny – is that China has ‘fabricated’ its official figures on transplant activity since 2015.

The claim comes from a 2019 paper in BMC Medical Ethics, a respected journal, and is quoted in last month’s US State Department report. Its authors include Raymond Hinde, an Australian PhD in statistics, and two long-term campaigners against ‘organ harvesting’ in China, Jacob Lavee, immediate past president of the Israel Transplantation Society and Matthew Robertson, a former journalist at Epoch Times, linked to Falun Gong, now a PhD student at The Australian National University.

Using forensic statistical analysis, they claim China has since 2015 used a mathematical formula, a quadratic equation, to ‘fabricate’ its official figures. ‘A variety of evidence points to what the authors believe can only be plausibly explained by systematic falsification and manipulation of official organ-transplant data sets in China,’ the paper concludes.

Their charge was met with vociferous response from China. ‘Report slandering China’s organ-donation data is laden with logical and academic fallacies,’ runs one headline in Global Times, a Beijing-based English language newspaper. The Chinese Medical Association says a retraction will be requested.

These allegedly falsified figures are emblematic of China’s claim to greater transparency and helped rehabilitate it in the eyes of the international transplant community (see graphic below).

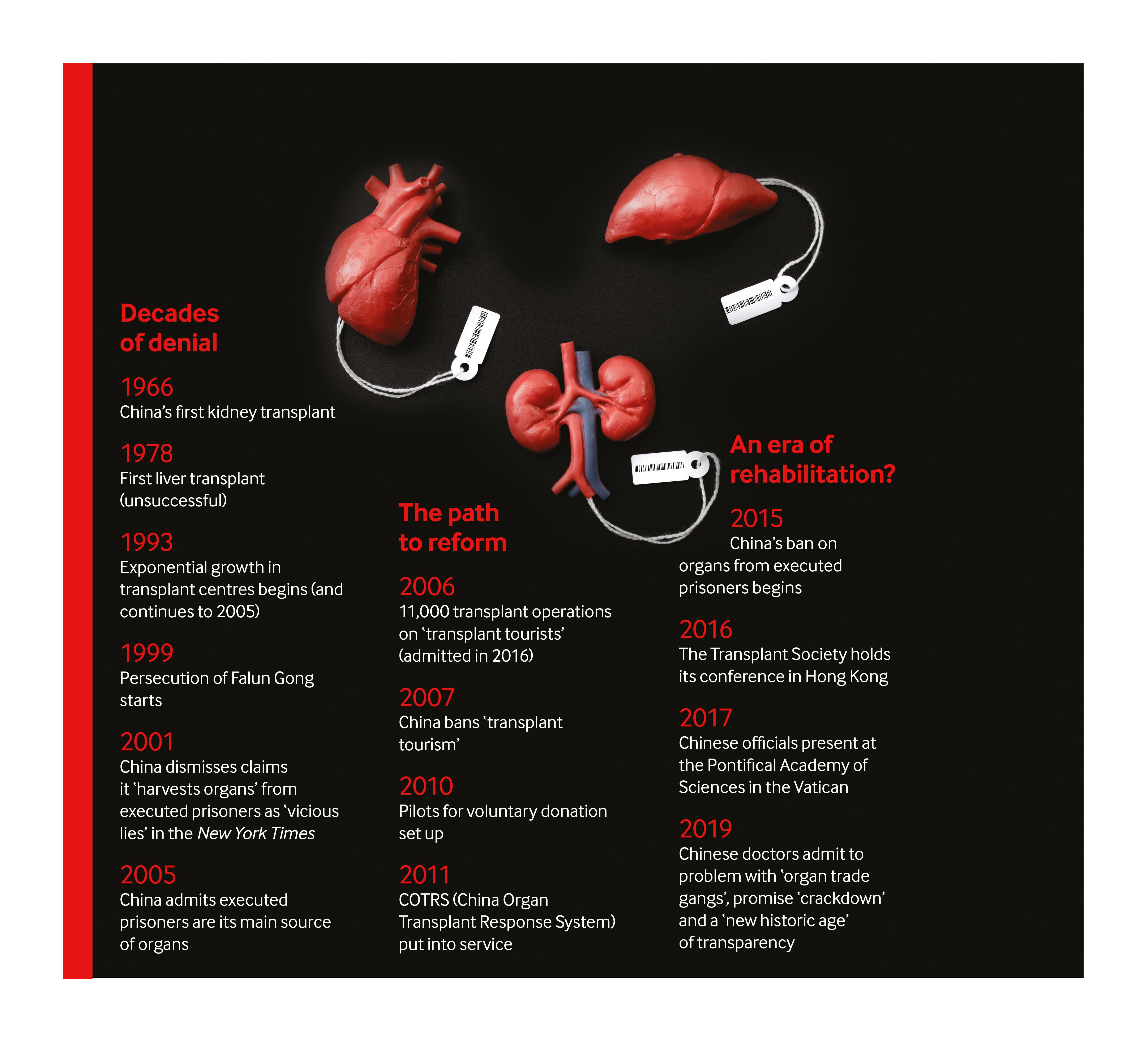

Decades of denial

Decades of denial

They’ve been presented at international conferences, including at the Vatican’s Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 2017. They’re pulled from the COTRS (China Organ Transplant Response System) that China set up as part of its plan to improve.

Before 2015, China’s reports to a WHO transplant surgery observatory, while regular, are questionable. The exact same figures appear for several years; the one for 2006 is thousands below the figure for the same year – reported by Prof Delmonico a decade later – for foreign patients alone.

Transplant operations reported to the WHO

Transplant operations reported to the WHO

Prof Lavee’s paper was examined for the tribunal by University of Cambridge statistics Professor Sir David Spiegelhalter. He describes its analysis as appropriate.

‘The close agreement of the numbers of donors and transplants with a quadratic function is remarkable,’ he adds. While ‘unable to ascribe specific reasons for the anomalies… they are certainly worthy of further investigation,’ Sir David’s review states.

Carrot and stick

Another reviewer, questioned by TTS (The Transplant Society), found the Chinese data ‘plausible’. This reviewer, University of Michigan professor of biostatistics Jack Kalbfleisch, told The Doctor the authors’ alternative claim of a ‘bold scheme of data manipulation’ was ‘more incredulous’.

TTS is an influential membership body for transplant physicians worldwide. It has worked with the WHO – using carrots and sticks – since 2005 to help China improve. Prof Delmonico is a former president and now chairs the WHO taskforce on organ donation and transplantation.

Following Prof Kalbfleisch’s review, TTS China Relations Committee rejected the claims of ‘falsification’ at a meeting in February last year, following a videoconference attended by Haibo Wang, China’s head of COTRS, its IT system. This decision is described by tribunal lawyer Hamid Sabi as a ‘white-wash’, in an email to TTS, published on the tribunal’s website. The tribunal did not approach Prof Kalbfleisch for his views.

Prof Lavee, a former member of TTS ethics committee, says its response to the ‘hard evidence’ of his paper and the tribunal is ‘disgraceful’. TTS had adopted an ‘ostrich policy’ towards China, he told The Doctor. ‘The silence of the world in general to those ongoing atrocities is unimaginable.’

The tribunal was, however, convinced ‘official Chinese transplantation statistics have been falsified’ and so ‘disregards’ them. It instead considers ‘as credible’ a far higher range of transplant operations from another piece of evidence it examined.

China’s latest figures show that 20,201 patients received organ transplants in 2018 from around 6,302 donors. The range accepted by the tribunal numbers is 60,000 to 90,000 transplants a year.

So how was the higher range arrived at? What does the alleged difference mean? The range is an estimate of China’s capacity to perform transplant operations. It comes from a 2016 report, Bloody Harvest / The Slaughter, by human rights lawyer David Kilgour, former Canadian politician David Matas, and US investigator Ethan Gutmann. Their estimates are based on bed and staff numbers, and likely activity, pulled from Chinese hospital websites, media reports and academic papers before – and a short time after – the 2015 ban.

Accepted as credible, the range opens an ‘incomprehensible gap’, the tribunal concluded, between it and China’s officially declared numbers of voluntary donors. This gap must have been filled, it concludes, by an ‘alternative source’ of organs. Organs from this source would have been ‘tissue-typed’ for matching from ‘donors unidentified’ in China’s official figures.

This alleged ‘alternative source’ is linked to prisoners of conscience by what the tribunal judgment calls ‘indirect evidence’. Former detention camp detainees had testified to being ‘systematically subjected to blood tests and organ examinations’, including ultrasound scans. Such tests are ‘highly suggestive of methods used to assess organ function’, it says.

Unethical testing

While many of these testimonies are from before the 2015 ban, China has since 2017 taken blood from millions of Uighurs in its remote Xinjiang province, according to US-based Human Rights Watch.

The tribunal’s claim of an ‘alternative source’ is further bolstered with evidence of short waiting times.

This is largely from records of more than 2,000 undercover calls to Chinese political figures, hospitals and doctors by researchers from the World Organisation to Investigate the Persecution of Falun Gong, an activist organisation, since 2006. Of the very few relevant ones placed post-2015, some respondents do offer waiting times in weeks, according to transcripts.

This opens another ‘unexplained’ gap – between the weeks-long waits offered in these calls and the months or years people typically wait for transplants in countries reliant on voluntary donation.

Together, this evidence of China’s previous practice of ‘harvesting’ prisoners in hundreds of hospitals, its oppression of those still confined in camps – including unwarranted medical checks – alongside contested doubts about its honesty, helped move the tribunal to a stark and certain conclusion.

‘There has been a population of donors accessible to hospitals in the PRC’ (People’s Republic of China) ‘whose organs could be extracted according to demand for them’, their judgment states. Falun Gong members were ‘probably the principal source’ and there was ‘no evidence of the practice having been stopped’.

Tribunal member and consultant paediatric cardiothoracic surgeon Martin Elliott is a former medical director of Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, where he performed heart transplants and ran its thoracic transplant programme. Prof Elliott says he would find it ‘very hard’ to believe China on organ transplants until it stops it ‘being a state secret’ and ‘opens its books’. Its records on donations and transplants should be open for cross-checking by neutral parties as in other countries, he says.

The ‘mismatch’ between declared donors and the 60,000 to 90,000 range ‘requires explanation’, he adds. He admits to not seeing ‘really hard evidence’ of what the unwarranted blood tests were for. ‘But you have to postulate explanations and they overlay with the other strands of evidence.’

WHO taskforce chair and Harvard Medical School professor of surgery Prof Delmonico has worked with Chinese doctors to improve practice for 15 years. He says the range relied on by the tribunal is ‘not consistent with a reality of performing that many transplants in one year in one country’.

The international community ‘does not deny’ the abuse of blood tests in detention but ‘linking of this abuse to transplants is a speculation’, Prof Delmonico says. He trusts China is committed to reform because of ‘the assurance of the minister of health of China’ whom he met in Beijing in December. So where does the evidence leave us?

Lack of trust

For all the certainty of the tribunal’s conclusion, there remain many unanswered questions.

China admits that an illegal trade in transplants continues.

Who is the source of the organs? How many are illegally taken each year? How much effort is made to protect those China already oppresses from ‘organ trade gangs’?

After years of covering up unethical practice, it’s no wonder that trust levels run low, that scepticism about improvements runs high, and that the balance of evidence tipped against China in the tribunal.

Dr Chisholm believes such questions can only be answered by a fully independent inquiry into China’s transplant practice, past and present.

‘Only by truly opening up to scrutiny and independent audit can we ever be sure that China has ended its reliance on unethical sources of organs for transplant and that it is committed to stamping out such unethical sourcing.’

The medical ethics of organ donation

Organ donation is a gift which is recognised in the well-known model of informed consent. This is valid only if it is given freely without the threat of punishment or coerced through reward.

Without proper consent, the act of organ donation has the potential to become coercive and a breach of human rights.

Informed consent is well established in the UK and worldwide. Under this, people must understand the benefits and risks presented to them and have the mental capacity to make rational decisions.

Restrictions to liberty in a prison environment make it highly unlikely prisoners are truly free to make independent decisions. Valid autonomous informed consent for donation under such conditions can therefore not be obtained.

Offer of payment to prisoners – or their families – for organs is another form of coercion. It creates incentives to increase commercial supply, which is linked to organised crime and unlicensed practice instead of expanding ethical voluntary donations with informed consent.

Transparency must be permitted

Dr John Chisholm

Dr John Chisholm

China insists it does not harvest organs from

prisoners but the only way to be sure is to have an independent investigation, says BMA medical ethics committee chair John Chisholm

Leading health and human rights organisations have expressed grave concerns for decades about allegations China has been trading in the organs of executed prisoners.

Far more worrying have been sustained allegations China has been executing prisoners of conscience ‘on demand’ to supply its commercial trade in organs.

The use of organs from executed prisoners violates international ethical and human rights norms: the threat of execution vitiates any possibility of informed consent. It is opposed by all leading international medical organisations, including the World Medical Association.

The practice of harvesting organs from prisoners of conscience on demand is a moral monstrosity – reminiscent of some of the most abhorrent practices of recent medical history. It has no place in medicine and must be absolutely prohibited.

As this thoughtful, painstaking and even-handed feature makes clear, China has admitted it has ‘harvested’ the organs of executed prisoners. It has also acknowledged they have been used to supply an extensive commercial trade in organs. It now says this practice is unlawful and is in the process of being stamped out. China remains emphatic in denying it has executed prisoners of conscience on demand to supply its organs. This is a deeply controversial area.

The Doctor’s investigation has not unearthed hard evidence the worst of these inhumane practices persist. But there is no doubt questions remain. A veil of secrecy hangs over China’s transplant system. In these circumstances, I believe it essential China agrees to a thorough, open and independent investigation of these allegations, commissioned by a reputable body, such as the World Health Organization. Only in this way can these grave concerns be properly addressed.

If what China says is true, it can have no good reason to oppose such an investigation. If it refuses, the world will make up its own mind.