Sixty tiny heads made with grace and precision. All of them different, probably modelled on real people. In daily use by the medical profession for years. And scientifically speaking, nonsense.

The overwhelming feeling you get from the Science Museum in London is one of progress. A grand procession of steam engines, flimsy-looking horseless carriages and space capsules a few dizzying decades of activity apart. To infinity and beyond.

The newly opened Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries tell a more nuanced tale. It’s not a simple march from darkness to the lights of a modern operating theatre. The history of medicine, and of it arriving at a point where it is not only fascinating and picturesque but actually does some genuine good, is one of innumerable rabbit holes.

The tiny heads were created for the entirely discredited discipline of phrenology, where patients’ characteristics and intelligence were judged by the size of their heads. Almost as pretty is the ceramic jar marked ‘leeches’, the coloured, stippled glass bottles of medicines which contained just a bit more arsenic than was healthy, and the gem-like amulets which may well have been patients’ best hope of recovery.

Bottles of medicines which contained just a bit more arsenic than was healthy.

Curiosity and compassion

The aesthetics are so good that when you reach a big lump of metal, four yellow rings with chipped paint, you think, ‘what’s that ugly old thing?’ but the early MRI machine has more than earned its place.

There is plenty that is useful and beautiful; it doesn’t have to be either/or. A forest of rods and coloured tags could be an art installation in its own right but is also a model of the myoglobin molecule made in 1960 by the Nobel laureates John Kendrew and Max Perutz.

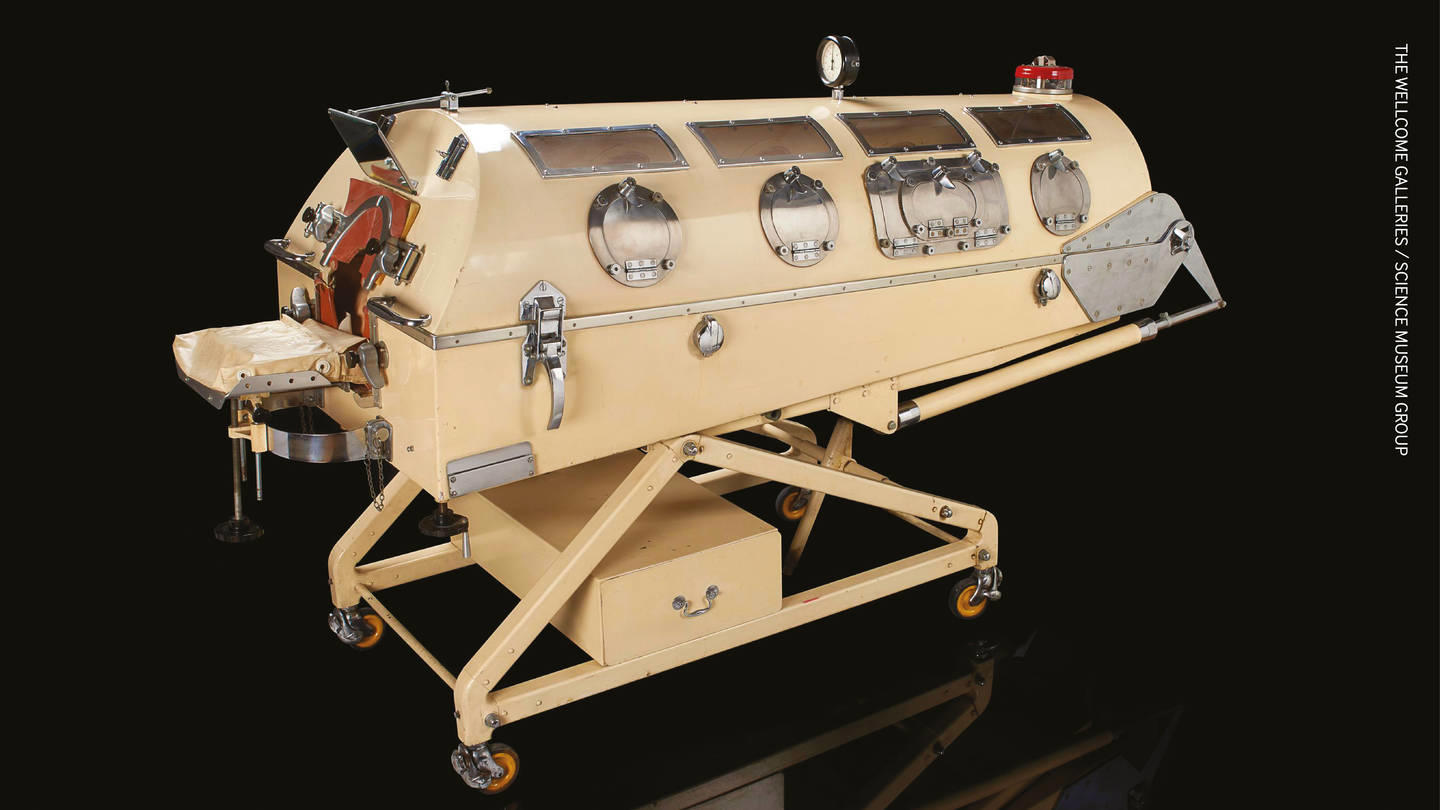

There are many such objects which are testaments to human curiosity and, by extension, compassion, such as a lancet used by Edward Jenner for the first smallpox vaccinations, an iron lung (pictured above) used by patients with polio, and protective clothing worn during the 2014 Ebola epidemic. In each case, the practitioners would have looked so strange, possibly even threatening, and yet all were working for a common good.

In some of the other 3,000 artefacts, you see a particular strength the Wellcome collection has always had, in its emphasis on the relationship between medicine and society.

There’s part of an old ‘bug van’, which within just about living memory used to put people through the humiliation of publicly transporting their few worldly goods away for fumigation during slum clearances. A strangely disturbing doll with a cigarette in her mouth and a plastic foetus in a jar below her. ‘Smokey Sue smokes for two,’ says the caption. A children’s board game from the 1980s to ‘build a better burger’ is poignant given what’s happened to the nation’s waistlines in the years since.

The models were treated with more respect than the corpses on which they were based.

Grave intentions

Doctors are not always the heroes in this museum. A heavy iron cage, known as a mortsafe, was for a time an essential hire when mourning the recently deceased, enough to protect the corpse from the roving attentions of anatomists until it had safely decomposed.

It’s a reminder that progress tends to come at a price. The crude, black, heavy iron of the mortsafe contrasts with the outstanding craftsmanship of the delicate anatomical models nearby but they possibly have a common, grave-robbing source. In which case the models were no doubt treated with considerably more respect than the corpses on which they were based.

Good or bad, life-saving or life-shortening, there is a common thread in the museum of medicine being a profession with a sense of identity, kudos and a culture all of its own.

How else can you explain the amputation saw (pictured above), more than 400 years old. All it needs is a strong frame and a good blade. But with its beautifully carved handle and elaborate metalwork, here was a practitioner who would cut off your leg with a dirty blade, with no anaesthetic and a filthy rag to bite on for the pain, but he’d do it with style and he’d do it with pride.