A SPECIAL INVESTIGATION

Garry Lovelock is not a religious man. But when the lonely nights sleeping on the streets, the ‘grubby’ washing in a McDonald's toilet and the endless fines for boarding trains without a ticket become too much he finds himself in church, praying – just hoping for ‘a helping hand’.

The other likely destination on those hopeless nights is the accident and emergency department at Nottingham’s Queen’s Medical Centre.

Mr Lovelock, 41, lost his house and employment after his wife died of leukaemia. When he is emotional and upset he drinks. It is the causal spark of a repetitive cycle in which he is picked up by the police, taken to an emergency department, sees a doctor after sobering up and is told he is fit to go. Not go home, of course. But go.

It is a costly cycle with the average interaction with the emergency department estimated at £297 by the NHS, not to mention the serious mental and physical toll this repetition has on Mr Lovelock, too.

‘There is so much of that – not addressing the root causes and just using sticking plasters [like seeing a doctor in A&E],’ Ann Bremner, who runs The Friary homelessness charity in West Bridgford, Nottingham, where Mr Lovelock has been provided a meal and support with his search for employment, says.

LOVELOCK: Trapped in a harmful cycle

LOVELOCK: Trapped in a harmful cycle

The cycle between the streets and hospital is far from the only one in which the vulnerable are trapped. Others – each as dehumanising as the last – exist, too.

Here at The Friary, there are scores of people who are regulars in other health services or the criminal justice system, for example. A Polish man being given a food parcel is one of those.

He says he ‘lost everything’ because he was convicted of a crime and sent to prison for two weeks. He is now unemployed, and his only routines are going to places like this for food and the regular check-ins with his probation officer.

‘I came straight from jail to the street,’ the man who asks to be called Grzegorz, says. ‘I have no home, no work and no money.

‘What do they expect me to do? A universal credit application takes at least a month and that means no money for five weeks and I have to start again every time [he is arrested].’

'This is definitely an austerity issue'

Stephen Willott

A friend, also at The Friary – who asks to be called Pavel – has epilepsy, which is difficult to manage while in and out of hostels or sleeping rough. Stephen Willott, a GP who does sessions with users of The Friary, manages his condition and is a ‘nice guy who does everything for me’ but it is clear Pavel needs significant support.

The Doctor has spent months in communities in Nottingham – meeting health professionals and their patients, people struggling to get by and the charities and organisations trying to hold together what remains of the UK’s disintegrating social safety net. Everywhere the stories have similar themes – services have been pared back to the bone and society is often unable or unwilling to intervene.

The tales of tragedy are everywhere you look. When The Doctor visits The Friary there is a man slumped outside the front doors – knocked out due to heavy use of the synthetic cannabinoid mamba, also known as spice. He has been in and out of an emergency department, crisis teams have been involved but because he has no home the authorities say there is no safe place for them to conduct a mental health assessment.

Instead, he is repeatedly charged with offences, offered no intervention, and continues to use vast amounts of drugs. ‘It’s incredible what he puts his body through,’ Ms Bremner reflects. And Dr Willott adds: ‘This is definitely an austerity issue.’

Life expectancy

All of the horrors seen here in this one moment on one day in Nottingham are stark reminders of the deterioration of health in this country. Before the pandemic, life expectancy – a key indicator of the nation’s health – had started to stall for the first time in a century.

For some of the most deprived areas, like many parts of Nottingham, life expectancy was starting to decline – something not witnessed for 120 years. And the amount of time that people spend in poor health has increased, with the gap in healthy life expectancy between the most and least deprived areas now nearly 20 years.

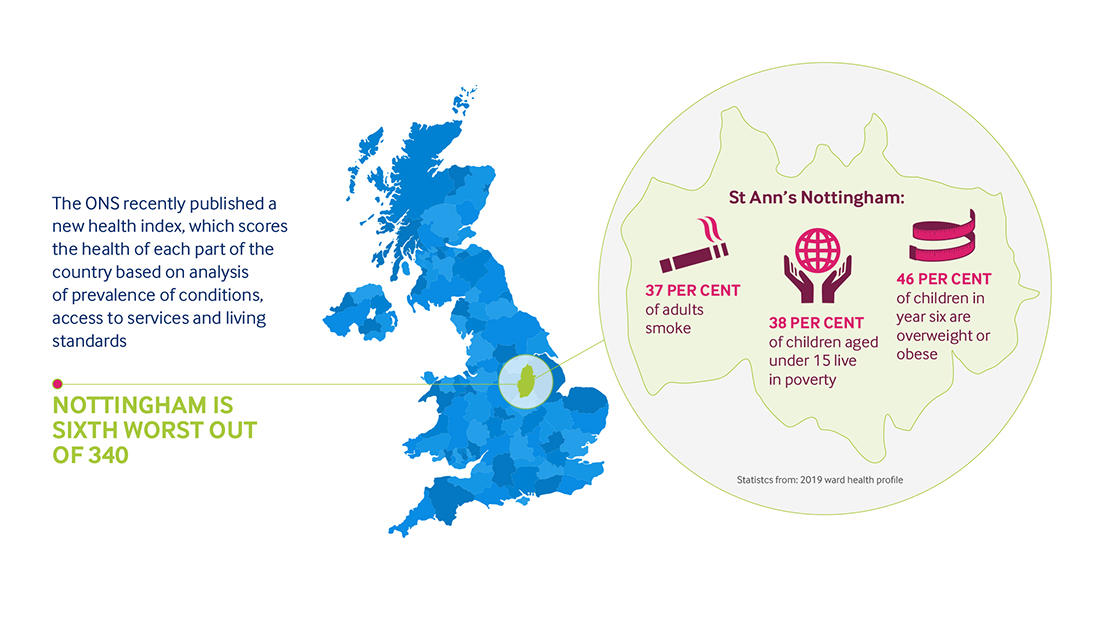

The picture is particularly bleak here in Nottingham. The ONS (Office for National Statistics) recently published a new health index, which scores the health of each part of the country based on a vast analysis of prevalence of conditions, access to services and living conditions. Nottingham is sixth worst out of 340.

Much of the regression nationally, and locally, is being caused by preventable illness. Relative to comparable countries, the UK has a higher amount of preventable illness, and those numbers are rising.

An estimated 29 million people in the UK are living with one of more long-term health conditions. The number of working-age people in Britain reporting multiple serious health conditions has rocketed by 735,000 in just two years. These figures are often worst in the most deprived communities

I came straight from jail to the street ... I have no home, no work and no money'Grzegorz'

The evidence suggests this deterioration in health is driven by austerity politics – political and economic decisions taken by successive governments.

Billions of pounds have been cut from public services and social security since 2010, decimating welfare and the social safety net and there are now far fewer services promoting good health.

People are dying younger, as a result, with the poorest areas hit the hardest. According to the Glasgow Centre for Population Health an additional 335,000 deaths have been caused by austerity in the five years before the pandemic – more than from the first two and a half years of Covid-19.

Cuts to central government funding for local government have meant cuts to public services that are essential to health – including housing, transport, children’s services, leisure and public health.

For example, spending on housing services and homelessness prevention declined by 50 per cent between 2009 and 2019. Street homelessness rose rapidly during this time, doubling between 2013 and 2018.

The number of homeless people dying also increased during these years and a reduction in funding for housing services is linked to increased deaths from drug misuse, accounting for an additional 1000 deaths between 2013 and 2019.

BREMNER: Root causes of poverty must be addressed

BREMNER: Root causes of poverty must be addressed

In 2020, The Doctor reported the story of funding cuts and failed procurement processes at an outstanding-rated GP practice in Nottingham which looked after thousands of the most vulnerable and complex patients in the city.

Commissioners wanted to decrease the funding per patient given to the practice – anything from £160 to £211 a head according to NHS digital – to around £110 a patient. The non-profit provider running the surgery said it would lose around £400,000 a year or have to make 40 per cent of staff redundant under the new terms.

TURRILL: Funding per patient cut back

TURRILL: Funding per patient cut back

‘It basically just fell foul of austerity,’ Jane Turrill, then lead GP for NEMS, which ran the surgery, tells The Doctor. ‘We got paid more money to look after, to provide the same level of service, to patients who find it difficult to access general practice and for us that was predominantly patients with severe multiple disadvantage.

'Over the years the amount of money that we got per patient was cut back and back and back. We just couldn’t fight a central thrust to move toward that goal of every GP practice getting the same amount per patient across the whole country.’

This austerity landscape is brutal for the most vulnerable and their health – but also remarkably complex and challenging even for those who feel able to advocate for themselves.

Jerome Barton had been sleeping in The Arboretum, a small but historic and well-loved park at the heart of the city, for around two months when The Doctor met him. He has qualifications and, until recently, worked in industrial cleaning, but struggled with depression and housing debt and ended up sleeping rough. The father-of-three says: ‘It doesn’t take a lot to fall out [of work and housing].’

If I can get a house, I can get a jobJerome Barton

For Mr Barton, who was in contact with local authorities and charities over housing, recent months had featured offers of beds in hostels surrounded by drug addicts. He chose to sleep on the streets instead.

‘For people who are clean it isn’t healthy,’ he says. ‘It’s really difficult.’ Mr Barton could hardly be described as picky – he just wants somewhere a roof over his head and access to buses to see his children.

‘If I can get a house, I can get a job - I’m confident about that,’ Mr Barton adds.

Spending on Sure Start declined from £1.8bn in 2010 to £600m by 2017-18BMA research

Spending on Sure Start declined from £1.8bn in 2010 to £600m by 2017-18BMA research

When speaking to health professionals, charities, and community groups across this city it is rare a conversation passes without reference to the loss of Sure Start. Spending on the programme declined from £1.8bn in 2010 to £600 million by 2017-18, resulting in over 1,000 Sure Start centre closures.

These closures came despite an IFS evaluation which revealed positive health impacts, including 5,000 fewer hospital admissions of 11-year-olds each year for children who participated, benefiting disadvantaged children the most.

Studies have also shown that cuts in spending on Sure Start have contributed to an increase in childhood obesity. Dr Willott describes Sure Start as ‘one of the very few initiatives that actually reverse the inequality of the poorest getting the rawest deal’.

BARTON: Just wants a roof over his head

BARTON: Just wants a roof over his head

This sort of neglect has hit hard across the country, but in few places harder than in St Ann’s – a particularly deprived part of Nottingham which has a tragic history of knife and gun crime.

According to the 2019 ward health profile 37 per cent of adults in this corner of the city smoke, 46 per cent of children in year six are overweight or obese and 38 per cent of children aged zero to 15 years live in poverty.

St Ann’s sits right on the edge of Nottingham city centre but retains a distinct sense of independence and isolation. In the 1960s the Victorian terraces here were knocked down as part of ‘slum clearances’ and replaced with a mazy prefabricated estate.

Just 50 years later this area feels impenetrable and cut-off. The shops at the precinct off the area’s Robin Hood Chase are boarded up and empty. There are precious few signs of life.

Just one door stands ajar on the precinct when The Doctor visits. A dimly glowing light fleetingly escaping out into the pedestrianised courtyard which the abandoned buildings share.

Inside, two apprentices – Dave Gregory and Fatima Woodward – are stacking tins, packets and vital supplies on shelving units which surround the rooms and corridors within the makeshift foodbank.

‘I was sitting having Christmas dinner last year when I just thought about people less well off. It got to me and I decided to do some volunteering,’ Mr Gregory, who retired from working in air conditioning and ventilation three years ago, says.

He describes seeing people daily who are ‘at the end of their tether’ – many in employment who you might not expect to see.

Dave Gregory

Dave Gregory

‘It’s really sad - you can’t put it into words that are strong enough and it’s getting much worse,’ he adds. ‘The truth is you don’t know how desperate you could easily be.’

Ms Woodward is a single mum and has taken on this apprentice role through a 13-week Government kick-starter scheme after initially volunteering. She has previously worked in hotels, doing housekeeping, but can only work during school hours now.

Fatima Woodward

Fatima Woodward

‘It can be sad,’ she says. ‘It’s quite hard – they are struggling to feed their kids. That is the most desperate moment.’

The foodbank is part of The Chase Neighbourhood Centre – a local charitable success story which has been supporting people in this deprived community since 1997.

Debbie Webster

Debbie Webster

Debbie Webster, manager of the centre, is something of a local hero having been involved in the local community since setting up a community group during the difficult 1980s in Thatcher’s Britain.

It started in the pub across the road and now there are 32 paid staff in a purpose-built community hub ‘delivering support to people in crisis’.

'Moving public health to local authorities has had a big impact on what doctors can do'

David Rhinds

‘Sometimes I feel quite pleased, but I wish we didn’t have to have any [staff],’ Ms Webster says. ‘What a sign of the times that is.’ She adds: ‘There’s so much demand. We won’t be able to help everyone and it is getting worse. It’s so worrying. We’re not the solution - we’re the sticking plaster.’

Here at The Chase every opportunity is taken to wrap care and services around people who need help. There are money advice staff, benefits advisors, digital support and language classes available, among many other things.

Sherealyn McPherson is one of those being supported when The Doctor visits. The 32-year-old mum of one has struggled with a host of mental and physical health problems, including arthritis and anxiety, for many years and is so exhausted and pained by work that looking after her daughter after a shift becomes incredibly difficult.

Staff at The Chase are supporting Ms McPherson with a tribunal around sickness benefits after she felt she needed to leave her last job due to illness. She also gets debt support here. With no money coming in, life is very tough.

‘It’s a real struggle, you just have to try to survive,’ she says. ‘I’m having to consider using the food bank – you get to the end of each month and you just don’t know how you are going to make it work. If it wasn’t for this place fighting for me I would have given up. It does get you down and that’s why my anxiety is so bad now. It all makes me wonder what the world is going to be like for my daughter. I try not to think about it – I’ve got enough on my plate already.’

It all makes me wonder what the world is going to be like for my daughterSherealyn McPherson

Speaking about her friends and family, Ms McPherson adds: ‘Everyone is struggling and finding it hard with rent and bills and things. I think we need a more compassionate system.’

Sheila Jones, employment support officer at The Chase, who has been working with deprived communities in Nottingham for 20 years says communities have broken down. She adds: ‘Society needs to invest in people. There are so few things around them… Everything has fallen away.’

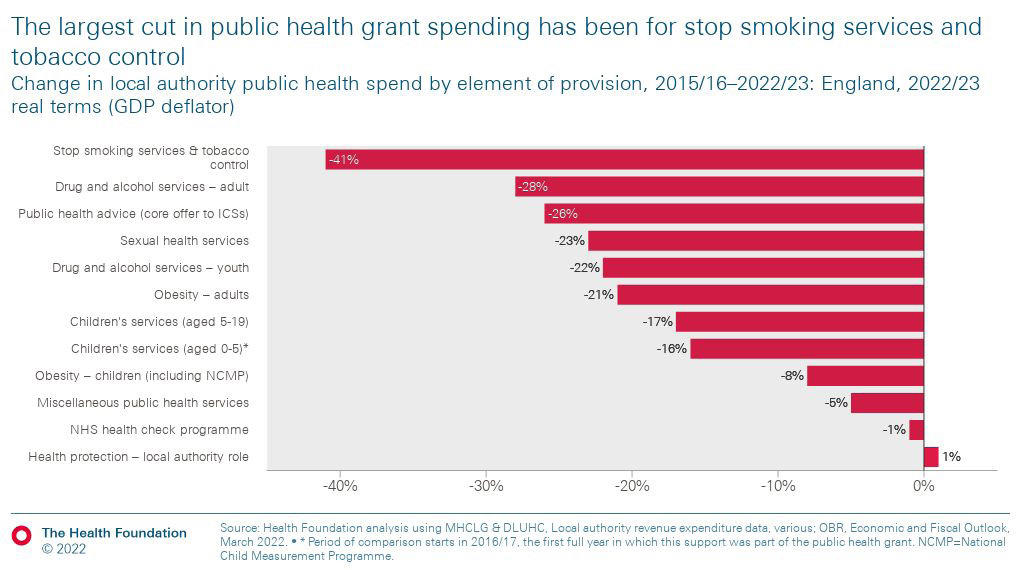

Few links between austerity and health are more obvious than in the cuts to the public health grant. With public health moved to local authorities from the NHS in 2012, owing to the Health and Social Care Act, budgets were under even more threat than those in the health service. This has also had the effect of creating silos and fragmenting services.

Nottingham consultant psychiatrist David Rhinds says: ‘It has made a big impact in what we can do as doctors. Before those changes I could see a patient in a clinic, prescribe for them, order investigations and scans and all that sort of thing.’ Now, few of those options are open to Dr Rhinds.

Jane Bethea, public health consultant, who up until recently worked for Nottingham City Council but is now employed by Notts Healthcare, the local mental and community health provider, adds ‘The function of public health was fractured terribly and we’re trying to get that back now – but we’ve got such low capacity… Frontline public health is under massive pressure.’

Tobacco use up

The public health grant has been cut by 24 per cent since 2015/16. Within those cuts stop smoking and tobacco control projects have been cut by 41 per cent, drug and alcohol services by 28 per cent and sexual health services by 23 per cent.

Dr Bethea says the cuts to smoking cessation services, for example, have had a clear impact. ‘You can see that we are actually bucking the trend in Nottingham now, in that smoking prevalence is increasing,’ she says.

Drug and alcohol services have been cut by 28 per centBMA research

Drug and alcohol services have been cut by 28 per centBMA research

Cuts have been higher in deprived areas like Nottingham. And those cuts come despite public health interventions being known to provide value for money: each year of good health achieved costs £3,800, compared with more than £13,500 if things are left until they require NHS intervention. Another familiar theme is that every budget cut seems to end up just costing far more down the line.

‘Some of these people I have been seeing for 10 years now,’ Dr Willott says, as The Doctor takes a seat in a consultation room at The Windmill GP Practice in Sneinton, just east of Nottingham City Centre. In the shadow of Green’s Windmill – a working mill built by mathematician George Green in 1807 – this practice runs what is likely the biggest shared care drug clinic in the East Midlands.

For Dr Willott it is an opportunity to make an immediate impact on the lives of the most vulnerable patients in this city - but the complexity and tragedy of some patients’ lives and the societal breakdown around them means sometimes harm reduction is as much as can be managed.

GPs warn of a growing prevalence of patients taking crack cocaine alongside heroin

GPs warn of a growing prevalence of patients taking crack cocaine alongside heroin

One patient is urged not to purchase the highly addictive and destructive crack cocaine alongside his daily heroin. This two-in-one phenomenon is a growing problem in Nottingham, Dr Willott says.

‘It is maybe the most prevalent now. And it is very dangerous.’ Another patient presents for his ‘pretty significant’ methadone prescription – an insurance policy that should ‘take the chaos’ and the ‘illicit means of getting drugs’ away from his life.

Next, we see a patient whose leg is so swollen the doctor’s fingers leave deep impressions in the flesh when making an assessment. He appears to be in a slight daze and says he has just had some mamba. Asked how he is finding life, he says: ‘It is just getting harder.’

For some people in this city using mamba is the easiest method of escapism. Mamba, in comparison to many drugs, is relatively cheap and it will remove users from full consciousness for a period of time, but Dr Willott says it is largely a ‘pleasureless’ drug where users are just ‘out of it’ rather than having a ‘nice high’. This, many health professionals have said to The Doctor, is among the most depressing indictments on the state of society – that escapism without any pleasure is desired.

The only time I will get help is when something really bad happensHomeless patient

The only time I will get help is when something really bad happensHomeless patient

After working through patients unable to come to the surgery in person and others seeking prescriptions The Doctor meets a homeless patient who is at his wits' end, having been unable to satisfy any landlords that he could pay their rents with the benefits available to him.

He says: ‘I’ve given up. It’s a waste of time. The only time I will get help is when something really bad happens. Everywhere I go nobody is interested. Maybe they will be when I’m dead.’

Several more patients file in and out. The personal circumstances seem to get bleaker with each visit. One of Dr Willott’s patients – a working-age heroin addict – died two days ago.

And another supplied a urine test which glowed scarlet red in the bottle due to being almost entirely made up of blood. The everyday horrors of many patients’ lives are beyond nightmare for most in society.

Rotten jaw

A final patient for the day arrives. He is happy to talk but is not well. He can’t lift his arm, he has a ‘massive abscess’ on one of his legs and half of his jaw has rotted away. He has just two teeth left.

The patient’s brother died recently after taking mamba. After three years on the streets he now has a flat and found services were more supportive following the death of his brother.

Asked about the future, he says: ‘Life is very tough. Cost of living? It’s the cost of just surviving, more like.’

Reflecting on another day in the clinic, Dr Willott, who is chair of the local drug deaths group, describes the reality of operating in a post-austerity health system with these patients as ‘increasingly brutal with each successive year’.

The patients here are cared for with great compassion and dedication but when housing is so difficult to access, other drug and alcohol services have disappeared and society seems to have forgotten them it is difficult to do much more than manage and cope.

And, sadly, with Dr Willott and his colleagues running these dedicated clinics in Nottingham, these patients are catered for in a way that many around the country are not.

Dr Willott says that 50 per cent of the drug deaths each year are of patients who are not in any treatment whatsoever, and that there is a crisis in people not being engaged with services.

That sense of postcode lottery is familiar across the city at The Level, in Radford, which sits among the relics of what was once the industrial heartbeat of this city – among the former factories that made millions of Raleigh bikes and the famous Player’s tobacco empire.

The Level is run by local housing charity Framework and works in partnership with Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust and a number of other charities and local organisations.

It was set up in 2018 after the NHS’s substance misuse service, The Woodlands, at the Highbury Hospital in the north of the city, closed down to make financial savings. These sorts of services are now few and far between – patients at The Level come, literally, from right across the country but there are only a small number of beds to go around.

GP Marcus Bicknell, who works there says the 2012 Health and Social Care Act left services vulnerable to budget cuts and describes the impact as ‘massive harm’. There are now only a handful – a count of five in 2020 – of inpatient units in the country and the health service’s addiction psychiatrist workforce has been decimated.

The traumas stored in people’s lives across this city are immeasurable. Much of that trauma is created in early-life, growing up in communities where poverty is normal and support unheard of. Doctors working at places like The Windmill and The Level already fear for their populations and now the worry of what is to come echoes loudly around the estates in Nottingham.

We’ve seen people with good jobs lose their jobs and their homesRachael Graham

Those fears appear to be justified. High inflation, more than 10 per cent in October, is making the cost of living increasingly unaffordable. Lower income households, who are already at a greater risk of ill health, are bearing the brunt of this as cost increases represent a greater share of their income and citizens Advice have reported a tripling of people seeking help because they couldn’t afford both food and energy.

In a grim summary of the situation one homeless person The Doctor meets jokes that the currency energy crisis is perhaps not the worst time to have no home to heat.

Last year, 4.5 million UK households were fuel poor, and this had significant health implications, with England recording an estimated 63,000 excess winter deaths in 2020-21.

Estimates suggest that 10 per cent of excess winter deaths are directly attributable to fuel poverty and 21.5 per cent are attributable to cold homes. Even with the government’s cap on energy costs, NEA (National Energy Action), a charity advocating for everyone to have a warm home, is warning fuel poverty numbers will rise to 6.7 million this winter.

Households with children have the highest prevalence of fuel poverty and cold homes are associated with reduced resistance to respiratory infections, including bronchiolitis, in children. Respiratory illnesses are more than twice as high in children who had lived in cold, damp homes.

In September, 18 per cent – 9.7 million adults – of all households were food insecure, meaning they ate less or went a day without eating because they couldn’t access or afford.

This has more than doubled since January. And one in four households with children have experienced food insecurity in the past month, affecting an estimated 4 million children.

This food insecurity is known to lead to adverse health outcomes – causing both malnutrition and obesity, one of the leading drivers of preventable illness and death, because healthy food, pound for pound, is much more expensive.

The problems with food insecurity are mental as well as physical as the risk of mental ill health from food insecurity is three times that of losing a job.

BICKNELL: Austerity: worst is still to come

BICKNELL: Austerity: worst is still to come

During the last financial year, the Trussell Trust supplied 2.2 million three-day emergency parcels - a year-on-year increase of 14 per cent.

At The Chase, Rachel Graham, an advisor and community engagement worker, says the need is so severe now that the centre is overwhelmed, and staff often have to direct people to CAB instead.

‘We’ve seen people with good jobs lose their jobs and their homes,’ she says. ‘For these people to come to a place like this is terrifying. It is also impacting people who are working. We anticipate this winter being a scary time - that question, heat of eat, will become an increasing issue. We are seeing this.’

Rachel Graham

Rachel Graham

Doctors across the city are deeply worried. Dr Turrill says: ‘I think it [the cost of living crisis] will push more people into that position [mental health crisis].

‘Ultimately, we will have people who are on that teetering edge of being able to cope and, suddenly, they’re not going to be able to cope anymore… You look at the price of food and heating and all that sort of stuff. And we know people’s rents have gone up… that puts people under a massive, massive pressure. I do think it will bring many more people into that arena of being more complex… I think that in terms of sheer numbers it is going to have a big impact.’

And Dr Bicknell adds: ‘I am very worried about this bit of austerity now… the worst is still to come even after everything we have seen. The fact that we’ve had these 12 or 14 years but the worst is still ahead of us is pretty terrifying really. It’s starve or freeze for many.’

It is a stark situation noted by bosses at Nottingham’s hospitals, who reacted to the effects of the cost-of-living crisis and austerity politics on staff in September by providing £2 subsidised hot lunches, with 2,500 bought on average each week.

Austerity, and the inequalities it has driven, have a huge impact on the NHS. There is currently a record of over 7 million people waiting for treatment, including 2.75 million patients waiting over 18 weeks. Last year, waiting lists increased by more than half, 55 per cent, in the most deprived areas, compared to a third in the least. Those in the most deprived areas were almost twice as likely to wait more than a year for treatment compared to those living in the least deprived areas.

The treatment and care of people living with often preventable, long-term conditions are responsible for around 50 per cent of GP appointments and 70 per cent of hospital days. GPs and other healthcare professionals also report that they spend around 20 of their time dealing with issues that are nonmedical but related to social or economic pressures.

We are seeing younger and younger people involved in violent crimeBob Winter

Bob Winter

Bob Winter

It is likely higher levels of fuel poverty will make things worse – the NHS will likely incur higher demand and higher costs from its effects. In 2019, it was estimated the NHS spends at least 2.5bn per year on treating illnesses that are directly linked to cold, damp, and dangerous homes.

And greater food insecurity will also add to pressures. Malnutrition is already estimated to cost the NHS in England £19.6 billion. Obesity related diseases are estimated to cost 6.5 billion each year. There were already more than one million hospital admissions due to obesity in 2019/20. International evidence shows that those experiencing severe food insecurity have health care costs which are 121 per cent higher.

The cost-of-living crisis is also likely to lead to a rise in demand for emergency and mental health care over the coming winter, including an above 10 per cent increase in inpatient mental health admissions and above 5 per cent increases in outpatient mental health contacts, 111 and 999 calls. Above 5 per cent additional funding would be required for mental health and emergency department services to cope.

Queen's Medical Centre

Queen's Medical Centre

It is not just the most obvious links between austerity and health that are causing great strain, though. Bob Winter, worked as medical director for the East Midlands Ambulance Service, National Clinical Director for Critical Care and Emergency and clinical lead in the Emergency Department at Nottingham’s Queen’s Medical Centre during the past decade, retiring just this year.

He says: ‘In hospital we saw an increase in knife crime and an increase in substance misuse. There’s not the safety net and there’s a disengagement of society that didn’t exist before. We are seeing younger and younger people involved in violent crime. If you had told me ten years ago that we would be teaching nightclub doormen and McDonalds staff how to manage a life-threatening haemorrhage, I wouldn’t have believed you… I would have laughed in your face. But that is where we are.’

Critical incident

On top of that, the NHS workforce is depleted and exhausted by more than a decade of working in under-resourced environments, with punitive pension taxes hanging over them and the ever-increasing risks of corridor medicine with patients locked in hospital due to a spiralling crisis in social care.

The week The Doctor meets Dr Winter, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, which runs the city’s QMC and City Hospital, declares a critical incident - an occurrence which was once highly unusual but now seems to be almost normalised. According to an e-mail seen by The Doctor staff were offered 30 per cent incentives to go and do extra shifts, such was the desperation of hospital managers.

And the week this piece was due to be published The Doctor received an anxious text message from one Nottingham doctor. It said: ‘I have never seen so many sick people waiting in corridors in ED on trolleys. Four corridors full.’

Dr Winter – who jokes that he realised he needed to retire earlier this year when he answered a bleep for a red trauma call in the middle of the night only to realise when he arrived at the hospital that he wasn’t even on call – says: ‘High level alerts are so normal now that you just read the email and shrug. There’s an element of “what do you expect me to do about it?” You get compassion fatigue. My big concern is we are normalising all of this.’

For Dr Winter, investment in the care sector and solving the pensions crisis, which is seeing clinicians give up work to avoid charges of thousands of pounds, are the easiest first steps to turning around some of these problems. He says: ‘I remember not that long ago a four-hour breach had managers jumping up and down. That’s not the case now. We have patients across the board waiting more than 24 hours to be offloaded from an ambulance. There’s nowhere to put the patients.’

MCKEE: Government ministers' policies harm health

MCKEE: Government ministers' policies harm health

Professor Martin McKee, the president of the BMA, says: ‘British doctors are tired. But it’s not just the long hours and heavy workloads. They are tired of picking up the pieces after government ministers whose policies are harming health and placing our NHS under unsustainable pressure.

And now, as ministers seek to balance the books, we face the return to the failed policies of austerity that created many of the problems we face today.

The BMA is calling on the Government to take ‘urgent action’ to halt the decline in the country’s health. Its proposals include upholding commitments to uprating benefits in line with inflation, exploring reforms to social security and wages to ensure both guarantee everyone access to the income they need to stay healthy and well and a commitment to uprating budgets so public services can cope with inflation.

In the longer term, the association is also urging ministers to plan to reverse the damage done by cuts over the last decade, to commit to keeping in place successful policies pledges on the drivers of ill health like the soft drinks levy and to publish and act on a health inequalities strategy that makes health a cross-government policy.

Professor McKee adds: ‘Britain can’t afford to get sicker. When it came to power in 2010 the coalition government chose to implement severe austerity. The first signs of economic recovery following the financial crisis were snuffed out. Government policies left entire communities behind.’

There is a huge amount of work going on across the city in a bid to hold together the remaining fragments of the social safety net and to work with the most deprived and vulnerable communities to improve their health and wellbeing.

Earlier this year, The Doctor was invited to a meeting of Nottingham’s SMD Partnership – a group of 40 to 50 staff and service users from health and social care, charities and other groups meeting every two weeks – which aims to support people facing a combination of homelessness, substance misuse, domestic abuse, offending and mental ill health.

Boarded-up shops near The Chase

Boarded-up shops near The Chase

It was a group in which the hope for the future belied the difficult context cities like Nottingham are operating in.

The group has convinced the city council to have SMD as a key priority for the local health and wellbeing plan and political and professional support seems aligned.

Professionals in the city are currently rolling out a programme which aims to see GP surgeries across the area provide enhanced services for the most disadvantaged among their populations and a vast new project, Changing Futures, is aiming to drive system change with these communities in mind.

Dr Bethea chairs the meeting. She says: ‘I think I’m the most optimistic I’ve ever been… and I’m quite a cynic.’ Dr Bethea cites the work of the volunteer and community organisations in the city and the willingness of health and care professionals to work together.

The optimism is much-needed in a city where so much has been lost – and there is so much work to do to protect and improve people’s health, yet so little resource to do it with.

Back at the Friary, Garry Lovelock is saying his farewells having finished the lunch volunteers have prepared. Despite everything he has been through, Mr Lovelock emanates the sort of positivity which might make most people feel ashamed of their everyday worries and irritations.

When The Doctor says goodbye, Mr Lovelock replies: ‘Why did George Michael have chocolate all over his face? ...Because he was careless with his Wispa.’

Mr Lovelock remains an optimist, who tries to ‘pick people up when they are down’. After more than a decade of austerity, communities in Nottingham are asking when, if ever, the government will be minded to do the same.

(Photos by Ed Moss and Getty)

Published on 1 December 2022