‘We are the modern-day manger, with room at our inn.’

The Holy Family Hospital in Bethlehem exists in two different dimensions.

'To the more-than 4,000 mothers who give birth there every year, it is a rare if not unique example of high-quality, subsidised healthcare available to a Palestinian population living in a profoundly difficult co-existence under occupation.

'To some of the parents and staff who work there, it is also about making amends to a couple who had rather fewer facilities at hand when they gave birth in Bethlehem just over 2,000 years ago.

With limited resources, we compromise with a little extra love and compassionDr Zoughbi

‘I feel this is reparations to the Holy Family,’ says Ambassador Michèle Bowe, from the Order of Malta, a religious lay order of the Catholic Church, which runs the hospital, and continues to run dozens throughout its 900-year history.

The hospital is there for those of any religion and those with none. Most patients are Muslims, reflecting the make-up of the Palestinian population.

And perhaps this is the third dimension – a place where patients and staff alike report a remarkable sense of harmony and common purpose in an otherwise divided land.

Strive for excellence

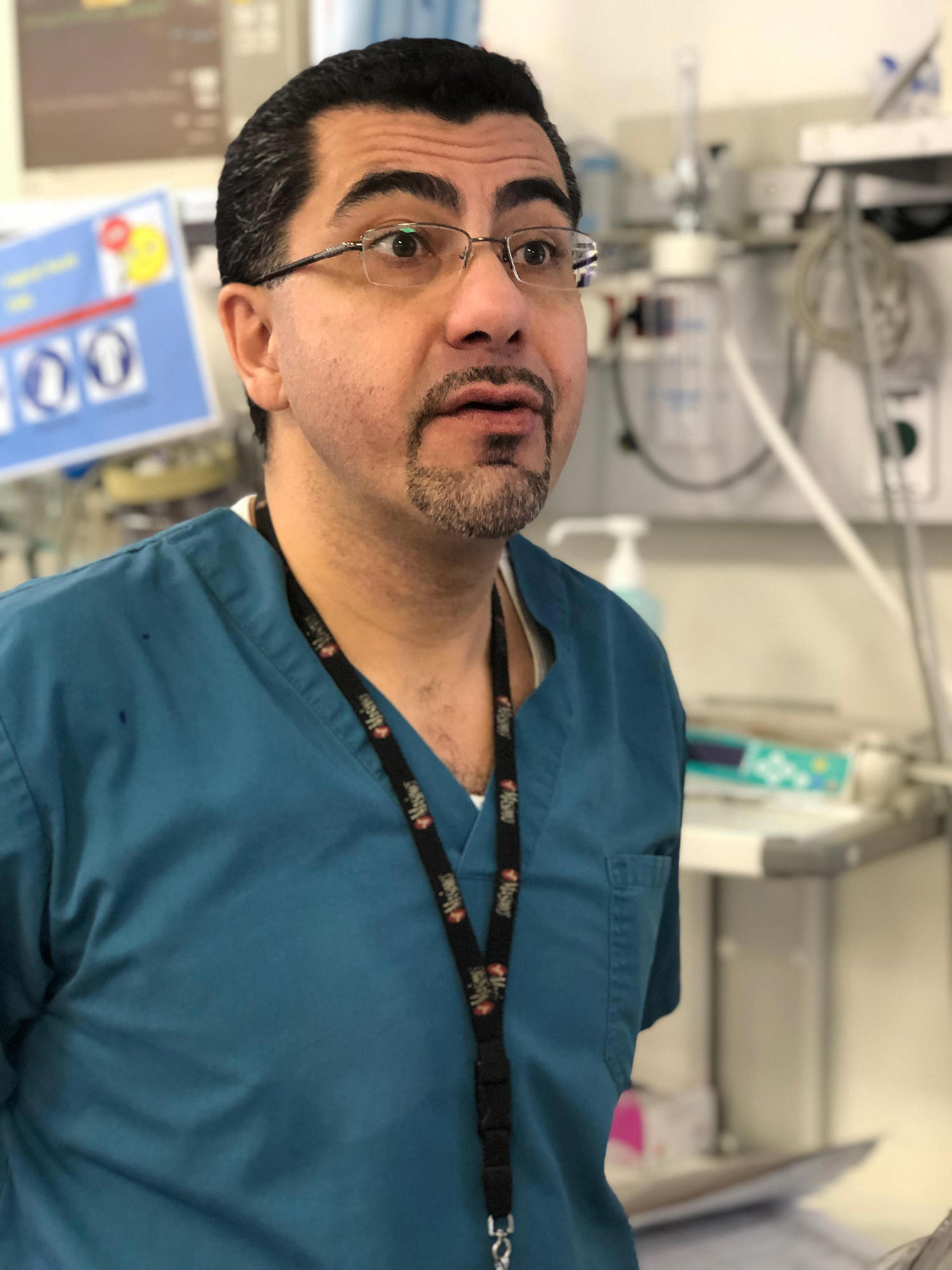

George Zoughbi (pictured below) is head of the neonatal department at the hospital. He is a native of Bethlehem, as were his parents.

‘I grew up in a conflict-torn region where medical aid was always a necessity, and I certainly had a dream of going to medical school.’

But the opportunities were just not there. So, after school, he went to Canada to pursue an undergraduate degree, then worked to raise money for medical school in the USA, before qualifying and starting his training in New York state.

ZOUGHBI: Dream of medical school

ZOUGHBI: Dream of medical school

With many, it would have probably ended there, a successful immigrant sending remittances home but focused on his new life.

But Dr Zoughbi came back in 2008 to compete his training and has remained ever since. It does not take long to find out why.

He has a profound sense of identification with Bethlehem, through his family and his faith, and a pride in his hospital, of which he says: ‘We strive to bring the latest advances in medicine and medical practice to our patients.

'Sometimes we have great challenges doing so mostly due to limited resources, but we compromise with a little bit of extra love and compassion through our work.’

Financial need

To outsiders, the idea of having ‘Bethlehem’ as a place of birth on a passport may be rather more quirky than a district general hospital in the Midlands.

There used to be, in fact, a small number of mothers, often foreign residents, who travelled from Jerusalem and other places to give birth there.

Whether it was for practical or cultural reasons, or just a desire for a good anecdote, these were often among the only patients who paid full fees at the hospital and the revenue was important.

The ‘separation wall’, a barrier built by the Israeli authorities which runs along the pre-1967 boundary as well as through parts of the West Bank, made such visits much more difficult.

Staff at work at the Holy Family Hospital

Staff at work at the Holy Family Hospital

This is only a tiny reason why the hospital is in considerable financial need. Much more profound is the effect of COVID on an economy which relies heavily on tourists and pilgrims.

Ambassador Bowe says: ‘Patients have only been able to contribute very little or nothing towards their care since March 2020.’

Services are always subsidised by at least half of the cost. Social workers then make an assessment about how much further subsidy they need and can increase it up to 100 per cent.

‘This 100 per cent is now nearly the norm,’ she says. In an area where almost half of the population are refugees, and many are uninsured, the hospital is – pardon the pun – delivering.

It also provides employment to 191 Palestinian families. And it runs outreach clinics to isolated villages for examinations, lab tests and screenings and can transport emergency cases to the hospital, a necessity given the day-to-day practical difficulties in travel.

Harmony at work

Despite the constraints, the hospital is equipped to deal with not only routine births but is a specialist centre for the more complex.

Almost a tenth of new-borns require neonatal intensive care.

‘The NICU has 18 beds and regularly saves babies as small as 500 grams and as early as 23 weeks,’ says Ambassador Bowe.

To her, and to Dr Zoughbi, both devout Christians, there is a divine element to the survival of vulnerable patients, and this is an overtly Christian institution.

A crucifix hangs in the intensive care department and to Dr Zoughbi, ‘it is our pride and our source of inspiration and it fuels the love that we give to our patients, regardless of their faith’.

It fuels the love we give to our patients, regardless of their faithDr Zoughbi

Dr Zoughbi acknowledges it is a very different environment from many hospitals in the West, where staff are not allowed to wear religious symbols.

But there is a multiculturalism here, perhaps not quite in the way it is interpreted in Britain, but a multiplicity of cultures nonetheless, working together for a common cause.

Staff cover for each other’s religious holidays, and Dr Zoughbi cannot recall a single religious argument between patients or staff in his eight years at the hospital.

I was interested whether the Christian patients at the hospital ever wanted to time their births for Christmas.

This would be quite a contrast with just about any other society where Christmas is celebrated, where the vast majority of patients, expectant mothers included, would rather be a long way from hospital on 25 December.

Christmas every day

The answer is complicated. Ambassador Bowe says: ‘It is always Christmas in Bethlehem,’ which could be misconstrued as Disneyfied optimism but is simply a statement of fact – Christmas mass is celebrated every day in the Church of the Nativity, which is less than a mile from the hospital.

Plus there are three Christmas Days, one each for the Latin and Orthodox rites and another for the Armenians. And one reason not to expect a surge in Christmas births is that she says many marriages in the region are followed quite quickly by a pregnancy, and it seems unlikely that conception would be timed deliberately for Christmas.

Bethlehem represents different things to different people. For those whose closest association with this town is a carol, there is perhaps little more than a certain festive continuity.

The Holy Family Hospital

The Holy Family Hospital

For devout Christians, it is a place not only where they can take direct inspiration from the nativity, but in some ways make amends for the primitive conditions in which it was forced to occur.

For the parents, there may be a mixture of motives, but surely all would agree with the Bedouin women who were surveyed by the hospital as to why they travelled so far to give birth.

Away from the villages where they themselves had been born, through checkpoints, to a large white building on a hillside marked with the symbols of a different faith to theirs.

The answer wasn’t complicated. They simply wanted the best for their babies.

Find out more about the hospital or make a donation

Photos courtesy of the Holy Family Hospital