At a time when long-standing concerns about a declining medical academic workforce have been compounded by the effects of COVID-19 and Brexit, support for medical academics and the medical research landscape has never been more critical.

The pandemic has exposed the severe staffing shortages that the NHS faces, and emphasised the importance of having enough educators to train more doctors to ensure the NHS is better staffed in the future.

Such a system is essential for both improved population health and an adequately staffed NHS.

Why do we need to strengthen the medical research system?

A strong medical research ecosystem within the UK is critical to improving population health outcomes.

Increased research activity within NHS organisations:

- directly benefits the patients involved in clinical trials

- is associated with improved hospital performance across services including reduced mortality rates, improved hospital outcomes and higher rates of patients who feel better informed

- improves the job satisfaction of healthcare workers, including reducing levels of burnout

- has economic benefits - every £1 invested is estimated to create a 30p return every year thereafter in the UK.

The impact of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has shown the central role the UK plays in global medical research and the value of medical academics.

However, while COVID-19-related research has been a UK priority since the beginning of 2020, many non-COVID-19-related research projects have been delayed or cancelled.

This is due partly to the redistribution of resources, including the redeployment of many members of the medical academic workforce. It is also due to reduced funding opportunities, largely because of significant cuts in charity research funding.

These issues are likely to compound longstanding medical academic workforce concerns. There is also the ongoing uncertainty of Brexit’s impact on funding opportunities and collaboration.

This makes it more difficult to attract people into academic research and teaching – which is crucial if we are to reduce future staffing shortages.

The capacity of the workforce must be increased

MASC (the BMA medical academic staff committee) has long raised concerns on the decline in the number of medical academics over the last 15 years and what this means for the future of medical research and education in the UK.

A reduction in the medical academic workforce represents a significant risk to:

- ongoing improvement in the quality of patient care

- the potential ability to improve population health

- the functioning of the research pipeline from new discovery to implementation at pace and scale.

The BMA has highlighted that, with an estimated shortfall of 50,000 doctors, England has fallen even further behind comparable EU nations.

The medical workforce crisis is severe among medical academics, with numbers increasing at a slower rate than for the NHS consultant and general practice workforces.

There are similar issues in several other specialities, especially in smaller specialities or in specialities not traditionally thought of as 'academic'.

Medical academics now make up a far smaller proportion of the medical workforce than has historically been the case.

With a significant proportion of the medical academic workforce aged 46–55-years old, a further decline can be expected as these individuals reach natural retirement age.

Recommendations

- The Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy must acknowledge the need for an increased medical academic workforce across all specialities and set out a detailed plan for how this will be achieved.

There has been a 31% rise in the intake of medical students in England between 2010/11 and 2020/21 - a welcome step in addressing the medical workforce crisis.

However, the medical teaching workforce (including grades professor, senior lecture and lecture) has only seen a 0.4% increase over the same period in England, resulting in the medical teacher to medical student ratio worsening over time.

Recommendations

- The Government must increase the medical teaching workforce to meet increased teaching demands and in turn address wider medical workforce issues.

- Higher educational institutions should promote careers in medical education and provide role models and mentors to inspire careers in this area.

A survey conducted by the Association of Medical Research Charities found that of 500 early career scientists, 40% were considering leaving research since the pandemic.

With many medical academics reliant on funding from medical research charities, large cuts to this sector mean that many projects were paused or cancelled with no clear timeline or certainty of being resumed.

This funding uncertainty, combined with pressures to remain in clinical work to deal with the post-pandemic backlog of care, could mean a significant and unsustainable drop in the number of early-career researchers. This will severely impact the future of medical research.

Recommendations

It is vital that support for early-career researchers is made a priority by employers. This should include:

- the promotion of mentoring and networking opportunities throughout training and early careers

- the use of role models in both education and research focused careers across all specialities

- the promotion of resources to support individuals navigating complex career structures and opportunities in academia.

For example, the medical academic training and careers hub, CATCH, provides information and highlights opportunities and rewards that a medical academic career can bring.

We believe that research should be better integrated into clinical careers. The workforce could be boosted by improving support for doctors to move between clinical work and academia throughout their career. This has the potential to create a more varied and sustainable workforce.

Current barriers to mid-career entries to academia include:

- a lack of information about the academic career structure including entry routes and opportunities

- insufficient research training throughout university

- a lack of flexibility between clinical and academic career paths and uncertainty about routes to return to clinical work

- a lack of part-time opportunities in academia, often due to time-limited funding.

Recommendations for the NHS and higher education institutions

- More information must be provided to all clinicians about entry routes and career progression in academia.

- Attractive opportunities in academic medicine should be promoted by employers and private sector industries.

- Higher education institutes must prioritise research training and experience throughout medical school.

- Employers must ensure that clinicians wishing to undertake research are able to easily switch back to a fully clinical career - guidance and support should be clear and accessible.

- Employers must create flexible and part-time job opportunities in academia to make this an attractive career prospect.

- Schemes to support clinicians who wish to undertake academic activity during their career should be developed.

For example, the 'new blood' clinical senior lectureship scheme offered five years of start-up funding for NHS consultants. The scheme saw a small increase in more senior medical academic positions between 2009 and 2017. - Flexibility between clinical work and academia should include better integration of research into NHS organisations.

The BMA has joined other organisations in calling for amendments to the Health and Care Bill to mandate that integrated care systems ensure NHS organisations conduct clinical research and publish research plans.

International collaboration is fundamental to clinical research and enriched health outcomes globally. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the global nature of medical research and the importance of an internationally diverse and agile research community in the UK.

EU citizens constituted over 15% of the UK medical academic workforce in 2019/20. Although the UK’s exit from the EU has not yet corresponded to a sharp decline in this cohort, concern remains that wider changes following Brexit may make the UK a less attractive place to train and conduct research.

The Marie Sklodowska-Curie actions scheme, designed to encourage the international mobility of talented researchers, saw a 35% reduction in individuals taking up fellowships in UK institutions between 2015 and 2018.

Barriers to coming to the UK

The introduction of the UK’s points-based immigration system in 2021 does include provisions for skilled workers. However, the end of free movement between the UK and the EU means increased restrictions, cost, and bureaucracy which may deter some overseas researchers.

Perceptions of the UK’s general attitude to immigrants and overseas doctors may negatively impact the UK’s ability to attract global research talent.

Recommendations

- The Government must ensure the UK continues to attract talented researchers including the promotion of clear and transparent guidance on immigration regulations and different routes available for academics wishing to work in the UK.

- The UK must be promoted as a welcoming destination for overseas academics.

Diversity of the workforce must be a priority

A diverse medical academic workforce is key to greater diversity in the research undertaken within academic medicine.

The research agenda is shaped by those who choose research as a career, and research is usually conducted on problems that are visible to and of interest to these individuals.

Diversity in the research and the patients involved will enhance patient care and potential solutions for health inequalities in by under-represented groups.

A diverse educational workforce is necessary so that all medical students can see people like them amongst their teachers and trainers. This encourages students to consider academic medicine or their educator’s specialty as a possible career option.

Survey data shows that gender disparity in academic medicine remains, with little progress being made in recent years.

In 2020, women represented over half of the UK’s population but less than 40% of the medical academic workforce.

The gender gap widens with increasing seniority. For example, in 2020 women made up 48% of clinical lecturers, 39% of senior lectures and just 22% of professors.

Structural barriers may include difficulties in accessing flexible or part time positions which can be combined with caring responsibilities, particularly when raising children.

Overcoming perceptions that less-than full time working patterns are not compatible with career progression is essential.

Progress to improve ethnic diversity in the workforce is slow. Just 0.4% of professors in medicine in the UK are black - this proportion has not risen since 2007.

Barriers to ethnic diversity such as structural factors and working cultures must be considered. For example, a 2018 BMA survey found that only 55% of black and minority ethnic doctors said there was respect for diversity and a culture of inclusion in their main place of work compared to 75% of white doctors.

Black and minority ethnic doctors were also more than twice as likely as white doctors to agree that bullying and harassment is often a problem.

The lack of representation among medical academics with other protected characteristics, such as disabled people and LGBTQ+ people, is likely to have an impact on the nature of research being undertaken, with ongoing implications for patient care and inequitable health outcomes.

Similarly, the small number of people with other protected characteristic amongst the education workforce means that students with these characteristics do not see people like themselves in the educational workforce.

Such non-inclusive working cultures and environments also risk marginalising or excluding future researchers and educators.

More must be done by employers to understand and overcome the barriers that those with protected characteristics face. They must understand how the intersection of multiple characteristics may compound disadvantages and create further barriers.

NHS and higher education institution employers must work to better understand and overcome the barriers faced by underrepresented groups in medical academia, specifically in senior posts.

They must actively work to improve academic culture and diversify the workforce.

Future funding must be secured

Evidence shows that every £1 invested in medical research creates an annual average return of 30p in terms of patient benefits and economic gains.

This return varies slightly across different diseases types, for example a 40p per pound return for cancer research and 25p return for musculoskeletal disease research.

These figures demonstrate the importance of sufficient investment in medical research to the wider economy, alongside the nation’s health.

A survey conducted by the AMRC found that of 500 early career researchers, 40% were considering leaving research since the COVID-19 pandemic

A survey conducted by the AMRC found that of 500 early career researchers, 40% were considering leaving research since the COVID-19 pandemic

The UK government’s target of £22 billion investment in research and development by 2024/25 has been extended to 2026/27.

The Government also announced in the 2021 autumn spending review that investment in research and development will increase to £20 billion by 2024/25 including £5 billion ringfenced for health-related research over the spending review period.

This increased investment is a welcome step towards achieving the UK government’s aim of making the UK a science superpower.

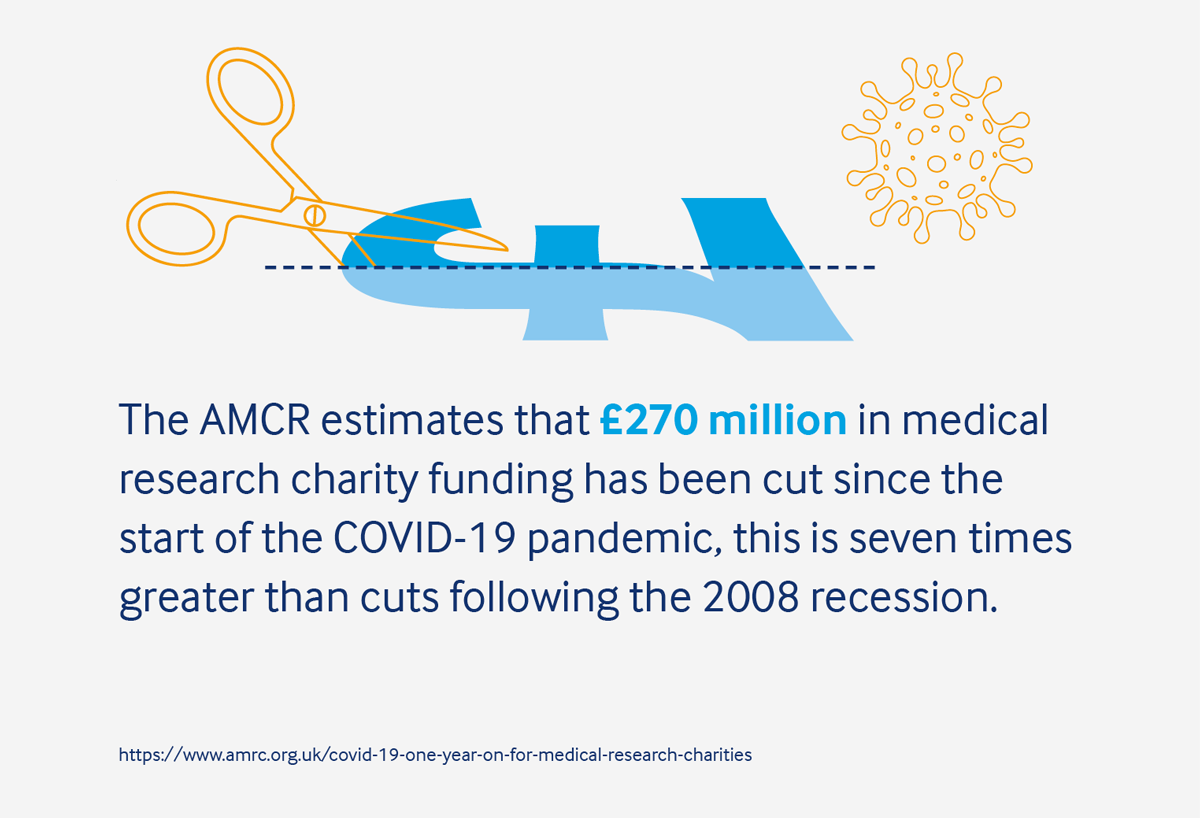

The announcement, however, did not specifically mention support for the UK’s medical research charities who have been hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Association of Medical Research Charities estimates that £270 million in medical research charity funding has been cut since the start of the pandemic, a cut seven times greater than the cuts following the 2008 recession.

This will have a detrimental impact on research projects and their translation into practice, and so on health outcomes of the UK’s population.

Recommendations

- The Government must ensure that some of the increased investment announced will be ringfenced to support the charity research sector and bridge the gap in research spending.

The Government must direct adequate funding into schemes to increase financial support for medical academics such as the previously mentioned ‘new blood’ clinical senior lectureship programme.

Recommendations

- The Government must provide make start-up funding available through such schemes to encourage movement between clinical care and academia and in turn increase the number of senior medical academics in the workforce.

Following Brexit, uncertainty remains around the UK’s access to Horizon Europe funding.

Research by The Royal Society found that the number of applications by UK-based researchers to Horizon 2020 decreased by 39% between 2015 and 2018.

This suggests that uncertainty around the UK’s access to European funding schemes is creating a barrier to research.

To be outside this relationship will have a long-term negative impact on the UK’s medical research capacity and reputation. It will encourage individual researchers, research teams and related industries to relocate to the EU.

Recommendations

- The Government must prioritise the association agreement between the UK and Horizon Europe and provide clear and transparent guidance for researchers.

As non-COVID-related research projects resume, and redeployed medical academics return to research, there is likely to be considerable uncertainty around funding for resumed or restarted projects.

This is especially the case for those supported by the charity research sector where spending is likely to take years to return to pre-pandemic levels.

There is also ongoing uncertainty that Brexit has created for funding opportunities.

Recommendations

- It is important that funding bodies recognise the challenges and uncertainty faced by researchers and remain flexible. This should include being receptive to cost extensions.