Health and social care in Northern Ireland is structurally integrated - distinct from the other systems in the UK.

It is widely acknowledged that patients don’t always experience an integrated service.

The system is currently undergoing a phase of reform.

Who receives social care?

- Adult social care is available to any person with eligibility needs who requires assistance.

- During the year ending 31 March 2016 there were 29,935 persons in contact with HSC (health and social care) trusts; a 10% increase over the last four years.

- 36% of contacts were by people in elderly care programmes of care.

- 40% of contacts were aged over 65 years.

- A significant proportion is delivered by informal unpaid carers. This is an important and vital source of care.

- It has been estimated that unpaid carers in Northern Ireland saves the local economy around £4.4 billion every year.

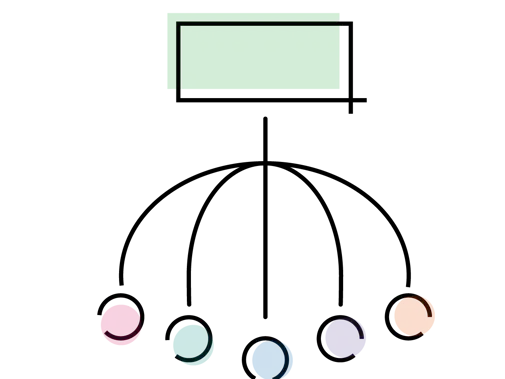

How social care is structured

- The Department of Health has the overall responsibility for the allocation of funding for health and social care.

- The HSCB (Health and Social Care Board) is the commissioning body for all health and social care services in Northern Ireland.

- There are five HSCTs (health and social care trusts) that have responsibility for delivering primary, secondary, community and social care.

- HSCTs commission care for people using a mix of statutory, voluntary or private providers.

Paying for social care

Adult social care in Northern Ireland can be means tested and there are different rules governing residential and domiciliary care.

In recent years there has been an increasing focus by governments to encourage people to plan and be responsible for their own care needs.

HSCTS have the power to charge for domiciliary social care services; however they do not normally do so. The exception to this is meals on wheels, which is a flat fee service.

Residential care is also means tested, this includes reviewing an individual’s capital levels, such as savings and property. There is an upper capital cap, £23,250, above which the individual is responsible for the full cost of their care.

There is also a lower capital cap, £14,250, under which the individual’s capital will be ignored in calculating how much they have to pay towards care.

Between these caps there is a scale of how much they would be expected to contribute.

Pressures on social care

Social care, like healthcare, is facing unprecedented pressures. These pressures are coming from increasing demand, alongside funding and workforce constraints.

Increasing demand

- By 2039 the population is expected to have increased by 5.3%.

- Projections suggest that there will be a large increase in the number of older people; the population aged 65 years and over is expected to increase by 74.4% between 2014 and 2039.

- The proportion of older people is also expected to rise: the share of the population aged over 85 years will increase from 1.9% in 2014 to 4.4% by 2039.

- The ratio of working aged adults to older people is shrinking and the population aged over 65 years will have surpassed the number of children by 2028.

- HSCTs provided domiciliary care services for 23,873 clients during the survey week in September 2016. This is 3% more than during the survey week in 2015.

Funding constraints

Financial pressures are significant as funding has not kept pace with greater demands for services.

There has been a shift in responsibility (and cost) between health care, social security and social care with aspects of long term care now being categorised as social care rather than health care. For example, care for dementia, Parkinson's and end of life care.

Workforce challenges

- In 2006 there were approximately 36,000 social care workers in Northern Ireland, the vast majority whom worked for the voluntary and private sector.

- Residential care staff constitute 44% of the social care workforce and domiciliary care workers are estimated to be about 32% of the workforce.

- Short and long term vacancies are increasing across all programmes of care and sectors.

- Migrant workers make up a large proportion of the adult social care workforce. As a result of the UK leaving the EU there are now uncertainties in the future of EU care workers’ status in the UK.

The BMA's view

Social care is an increasing area of concern for the BMA.

We believe that the significant pressures in social care is a direct result of inadequate resourcing. To look after patients well, doctors need social care to be well-funded and adequately staffed.

We have raised concerns that there does not appear to be a mechanism to capture and disaggregate spending on social care, despite the integrated structure.

In addition, improved integration between health and social care services is needed to ensure patients move between the two services easily.