In charge of the drinks trolley

Bashir Qureshi’s first Christmas in the UK in 1964 was very white – and not just because it snowed.

He had arrived at Whipps Cross Hospital in east London from Pakistan that September, and was still adapting to British culture when Christmas and its traditions arrived in force.

‘On Christmas Day in London, everything was covered with snow,’ says Dr Qureshi, then a 29-year-old house officer originally from India. ‘And I noticed for the first time that everyone was white except me: the patients, doctors, nurses, paramedics, porters, and the cleaners.

‘As a child, I learnt angels were white, made of light. I thought I was in heaven.’

A consultant dressed as Father Christmas carved the turkey on the ward and poured every patient their favourite alcoholic tipple, ‘including the one with alcoholic cirrhosis’.

Dr Qureshi pushed the wine and spirits trolley, while the formidable ward Sister handed out the drinks with an uncharacteristic smile.

‘Pearly kings and queens came to the hospital, sang carols and danced,’ says Dr Qureshi. ‘England was so peaceful, everyone looked happy. It was magical.’

ANOTHER ERA: Dr Qureshi on Christmas Day in 1964 at Whipps Cross Hospital, London, where he was a house officer

ANOTHER ERA: Dr Qureshi on Christmas Day in 1964 at Whipps Cross Hospital, London, where he was a house officer

But that first Christmas was also a crash course in British body language and tact for Dr Qureshi.

‘I joined the nurses in carol-singing, without opening my lips. I didn’t know carols or the tune, but I joined in.’ The ward Sisters were powerful and fierce, he recalls, ‘but nicer at Christmas’.

It was strange enough that several of the charge nurses were male, but some of their gestures were very disconcerting. When one male charge nurse advised Dr Qureshi to prescribe laxatives for every patient so the nurses wouldn’t have to bother him in the night, the nurse followed up the advice with a wink.

‘I was taken aback because winking is a sexual gesture in the east and I’m a strictly heterosexual soul.’

Language had its trip hazards too. ‘A staff nurse asked, “Would you like a date this evening, doctor?” “No,” I replied, “I find them hard to eat.” I thought turkey was a country. My English was different from the English and I am still learning.’

Dr Qureshi, who trained in Pakistan, was one of the 18,000 doctors from south Asia to be given work permits by the UK Government in the early 1960s, in response to an appeal by then health minister Enoch Powell. He has stayed in London for almost six decades.

Pearly kings and queens came to the hospital, sang carols and dancedDr Qureshi

Christmas traditions have become more familiar over the years. But Christmas has sometimes been demanding in other ways.

‘One night in 1966, I was on call at a hospital in London, when I was called to see a nurse who had died after jumping from a window,’ recalls Dr Qureshi. ‘I noted then that at Christmas, couples meet and split. Emotions are high and it is wise to care for mentally ill patients as much as possible.

‘When I worked at Christmas, I was paid double and I served all patients with double energy. I knew that patients who arrived during Christmas were more ill.’

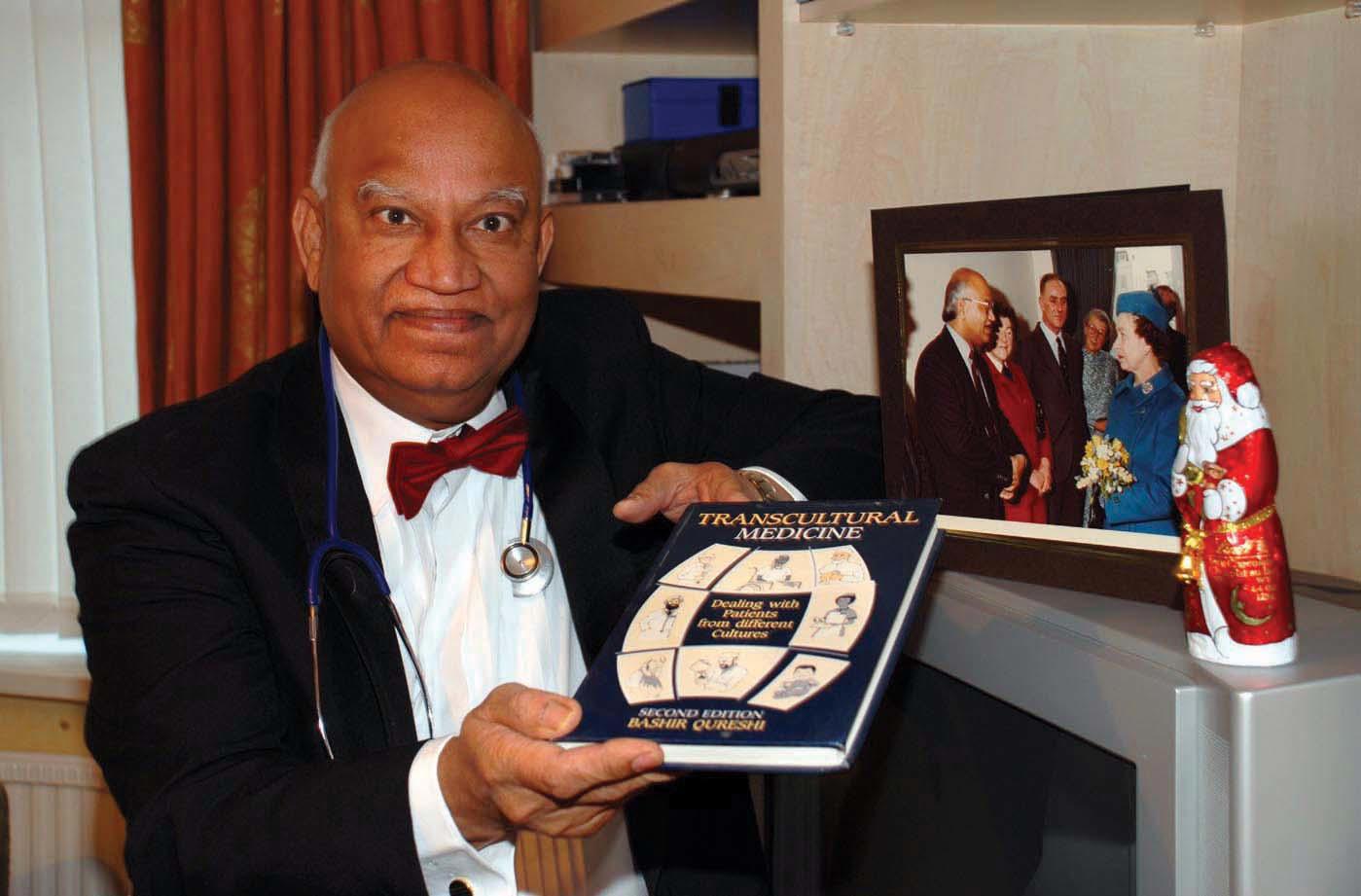

Dr Qureshi with one of his medical publications

Dr Qureshi with one of his medical publications

After four years in London hospitals, Dr Qureshi worked as a GP for 47 years, and still has a licence to practise, issued during COVID.

He is also an expert in transcultural medicine, lecturing and writing on how to interact with patients of different cultures, ethnicities and religions, and an expert witness in cases of clinical negligence.

That first Christmas of ’64, Dr Qureshi recalls that he had ‘thick black hair, a moustache turning upward, slim figure and no sense of humour’. Dr Qureshi is now in his 80s and ‘no longer needs a comb’ but he is starting to get the measure of the English.

‘I’ve learnt the English sense of humour and that often, what is said means the opposite. An Englishman might say, “I may be wrong,” but he really means that he is right.’

When Christmas comes early

Feelings run high at Christmas and never more than when you fear it may be your last.

For the team at Birmingham Hospice, there’s an emotional intensity to their care at this time of year and they pull out all the stops for their patients.

And if that means celebrating Christmas in September as they did for one man last year, then so be it.

For ‘12 days of Christmas’, a patient with no family had daily presents, a giant inflatable snowman, fake snow and a real Santa.

During Christmas proper, every patient in the Erdington and Selly Park inpatient units has presents, as well as a Christmas tree in their room and Christmas dinner of their choosing if they would like them. The local community goes into fundraising overdrive too, with raffles, jolly jumper days and Rudolph runs.

PALLAN: It’s about making every moment matter

PALLAN: It’s about making every moment matter

‘When people have a life-limiting illness, they have a chance to make the most of whatever time they have left,’ says Shurma Pallan, a specialty doctor who provides palliative medicine in the hospice and the community.

‘So we always do the best we can, so that they can live well and make every moment matter for them and their loved ones. When people first come here, they say, “It’s like a warm comfort blanket around you, as soon as you come in.” Nothing’s ever a bother.’

One question has dominated Dr Pallan’s conversations with patients and their families for months now.

‘Throughout the year, a lot of our patients will ask us: “How long have I got?” But when it comes to the end of the year, it’s more often, “Am I going to make it to Christmas?” Or “Is my family member going to be here for Christmas?”

‘Christmas is an important milestone, even if you don’t celebrate it, because it’s linked with the new year when people make new plans and reflect on the year they’ve had with their loved ones. It brings up a lot of emotions.’

‘LIKE A WARM BLANKET’: Staff and patients at Birmingham Hospice

‘LIKE A WARM BLANKET’: Staff and patients at Birmingham Hospice

Most of Dr Pallan’s patients will not see another Christmas so the festivities too can evoke mixed feelings. ‘One patient changed her mind about what decorations she wanted on her Christmas tree on a day-to-day basis but that was fine: we want to make that difference for our patients. But we don’t force Christmas on them.’

For all the jollity, carols and roast turkey, it can be a very difficult time for patients who are struggling with their symptoms or for relatives whose loved one is close to death. Like everyone on the team, Dr Pallan is generally on call for one day over the Christmas period and she has worked Christmas Day.

‘When someone dies at Christmas, that’s always going to be hard for that family as an anniversary because you can’t avoid Christmas at this time of year. It can be a constant reminder of their loss.’

Working over Christmas can be hard for the medical team too: ‘not taking work home’ becomes doubly important at this time of year. But it’s easy to be ambushed by personal connections and feelings.

‘As a human being you can’t help making similarities with people you meet, someone who’s the same age as me or with similar-age children as me.

Patients ask, 'Am I going to make it to Christmas?'Dr Pallan

‘And it’s somehow harder when you see people in their home, in their environment, and you’ve got that little extra insight into how they live.

‘Later, whilst typing my notes and reflecting, I tell myself I’ve done as much as I can to help my patients. I can’t stop them from dying but I can make a difference in the way that they die.’

The multidisciplinary team has a monthly debrief together, called ‘Learning from deaths’. It’s an opportunity for staff to share their feelings and experiences around deaths in the previous month and review if anything could be done differently.

This shared reflection is an important part of protecting the team and their wellbeing: they look after each other.

But staying boundaried is often harder at Christmas.

‘We try to separate out work and home life for our own wellbeing. But January’s meeting will probably be busier because it’s that time of year when people find it a bit more difficult.’

Miss World on the wards

From her earliest years, Olivia Curtis learnt that ‘Christmas Eve was for family, Christmas Day was for the hospital’ – because Granddaddy insisted upon it.

Her grandfather, Robin Denham, would spend every Christmas Day visiting every ward, whether or not he was on call as an orthopaedic surgeon.

He took very seriously his role of carving the turkey for his patients as the senior consultant – and always dressed up for the occasion.

Indeed in 1964, the year of Dr Qureshi’s first ‘white Christmas’, Mr Denham was making a memorable appearance as ‘Miss World’ in Queen Alexandra Hospital in Portsmouth. He would often take his children with him, dressed as elves or angels, to hand round the plates and be spoiled by the nurses.

His granddaughter Olivia is now Dr Curtis, a specialty trainee 7, who completes her respiratory training this month in Kent.

When she has worked over Christmas, her grandfather’s example has always helped.

THE ENTERTAINER: Mr Denham carves the turkey with Dr Curtis’s aunt and uncle as children

THE ENTERTAINER: Mr Denham carves the turkey with Dr Curtis’s aunt and uncle as children

‘I think he felt it was his responsibility to be there because they were his patients,’ says Dr Curtis. ‘But also, he felt that Christmas wasn’t a time to be by yourself because you were in hospital: he didn’t want his patients to be missing out. It was very jovial and cheerful with lots of crackers and silly hats.

‘The way he prioritised his patients reminds me how important our work during the holiday period can be. It has always felt worth it and important to be there.’

Decades later, his family still exchange gifts and have their ‘big dinner’ on Christmas Eve.

It works well for them: Dr Curtis has a sister who is a midwife and another who is a stage manager in the West End so any time together around the Christmas table is ‘always a bit of a Christmas miracle’.

But it’s mostly because of Granddaddy and the tradition he started.

He felt that Christmas wasn’t a time to be by yourself because you were in hospitalDr Curtis

Mr Denham’s daughter – Dr Curtis’s mum – still talks fondly of childhood Christmas Day at the hospital, even though she shared her father with his patients.

Yet, it was Mr Denham’s grandchildren who followed him into medicine: a midwife, a nurse and two doctors.

‘Granddaddy was a bit of a cliché as an orthopaedic surgeon because he was very good at woodwork, made lots of furniture,’ says Dr Curtis. ‘Because I was interested in medicine from quite a young age, he’d always show me bits of bone and models and strange X-rays.

‘He was a big part of our growing up: he was always very encouraging and larger than life, quite eccentric.’ Mr Denham was also something of a pioneer, with inventions such as a knee replacement and the ‘Portsmouth method’, an external bar to fixate tibial fractures.

‘Work was very important to him, part of who he was and how he defined himself.

‘We always think of Granddaddy while planning our Christmas Eve: we know it’s because of him that we do things that way around.’

CURTIS: Inspired by her grandfather’s dedication

CURTIS: Inspired by her grandfather’s dedication

A research post and two periods of maternity leave in recent years have meant Dr Curtis has not worked over Christmas and New Year for a while – but she used to, quite often.

There may not be turkey-carving on the ward these days but teams still work hard to bring festive cheer: Christmas trees made of latex gloves, plenty of tinsel, carols on a loop and (a specialty in respiratory) cartoon angels with lungs for wings.

Sharing good news, allowing people home, is particularly heartening at Christmas. But bad news can feel even more heart-breaking. There’s a real need for sensitivity.

‘I tend not to wear Christmas jumpers, or too many comedy things, because I don’t want to have to be breaking bad news wearing a reindeer jumper,’ says Dr Curtis.

‘But I know some people think differently: they want to be projecting as much joy and happiness as they can in case people are feeling sad and it helps them.

‘For people who get sick or die around Christmas time, it will change their families’ Christmases forever. And so being able to care for them as kindly or as peacefully as possible – important parts of medical care throughout the year – feels a bit more important at Christmas.’

This Christmas, thoughts of Granddaddy will be particularly strong for Dr Curtis: she starts a new role as a consultant next year.

‘I’ve been thinking about whether, next Christmas, I’ll do the same for my patients as Granddaddy did. I must admit I’m not certain.

‘But I am expecting to have to go into work over Christmas at some point and it’ll be a good opportunity to talk to my own children when they’re older about what really matters at Christmas.’