It can be hard to discern the man behind a name linked with medical firsts, prestigious awards, celebrity and even royalty. It is easy to draw the wrong conclusions from clichés.

Professor Sir Magdi Yacoub made his name as the cardiothoracic surgeon who pioneered daring procedures, took on ‘impossible’ cases, pushed past others’ disapproval. He drove fast cars, worked preposterous hours and counted Omar Sharif and Princess Diana as friends. He also saved thousands of lives.

Today, at 88 years of age, he is in reflective mode, having collaborated on a recent biography of his life.

For someone who used to distrust the media, he is remarkably open now in discussing those early, controversial days of surgical firsts. He is also remarkably unassuming.

For all his determination to extend the boundaries of surgery and science, those cases which saw his name and his hospital splashed across the headlines took their toll, he tells The Doctor. Surgeons don’t always deserve their ‘unfeeling’ reputation.

‘Actually, they suffer massively, because they are human beings after all, and they have emotions,’ says Sir Magdi. ‘And they do care, a lot more than people think.’

He is undoubtedly an extraordinary man: he won a scholarship to medical school at 15. Yet, what has always defined and driven him, and disconcerted his critics, is an extraordinary sense of purpose. ‘My primary duty is to my patients, not to the media or even to society at large,’ he says in his biography.

Ruffling feathers

The UK has adopted Egyptian-born Sir Magdi as its own and lauded him for his many achievements. These include the UK’s first arterial ‘switch’ operations, Europe’s first heart-lung transplant, the world’s first ‘live lobe’ transplant (of lung lobes donated by living patients) and perfecting the Ross procedure (replacing the aortic valve with the patient’s own pulmonary valve).

He was knighted in 1992 and awarded the Order of Merit in 2014, the highest honour in the gift of the British monarch. He’s a Fellow of the Royal Society and of the Academy of Medical Sciences. He is a national hero in Egypt, pictured alongside footballer Mo Salah in a mural in Sharqiya where he was born. Arriving in Britain aged 25, he worked under leading heart surgeons Professor Sir Russell Brock and Sir Donald Ross: the list of his colleagues and mentors reads as a Who’s Who of cardiac surgery.

Yet, he often felt like an ‘outsider’ and Harefield Hospital, in Hillingdon, where he was appointed consultant cardiac surgeon in 1969, was a small hospital, vying for position with bigger London centres.

Immediately, Sir Magdi started ruffling feathers. He wanted to increase Harefield’s output from about one open-heart operation a week to 10.

Colleagues were awed and baffled by his stamina: he often worked through the night, snatching only a few hours of sleep or relying on brief catnaps, often in theatre. He was also known for his calmness and dexterous, outsized hands.

Some people say, ‘You’ve done this new procedure for your own benefit, to be famous’. Never!Sir Magdi

‘During sleep, your brain continues to try and solve problems,’ he says now. ‘So, if I have a problem, for example, operations which I have not done before, I digest it so much that the following morning, I can do it very quickly, faultlessly, because I’ve thought about every tiny bit throughout the night.’

Sir Magdi quickly made his name treating complex congenital heart abnormalities, performing the first ‘switch’ operations in the UK on babies born with their pulmonary and aortic arteries the wrong way round.

Sir Magdi teaching at the Aswan Heart Centre in 2014 (credit: Magdi Yacoub Heart Foundation)

Sir Magdi teaching at the Aswan Heart Centre in 2014 (credit: Magdi Yacoub Heart Foundation)

But he was also gaining a reputation as a maverick. He hit the headlines in 1975, when he linked one-year-old Scott Molloy’s circulatory system to that of a baboon, to provide life support. The baby and baboon died.

He was certainly driven – not least to prove wrong his father, a general surgeon, who had told a young Magdi he had the ‘wrong temperament’ for surgery. But it was the presenting need that drove him, not personal ambition.

‘I believe the patient-doctor relationship is sacred,’ he says. ‘The patient leaves his life entirely in your hands; that’s a massive responsibility.

‘Some people say, “You’ve done this new procedure for your own benefit, to be famous”. Never! I would only do operations if the patient has nowhere to go and is desperate. And I think very hard: how can we save this patient or at least help them and buy time until we have something even more new to offer?’

Ethical debate

Surgeon Christiaan Barnard performed the world’s first heart transplant in South Africa in 1967; Donald Ross conducted the first in the UK the following year. Neither patient survived more than a few weeks: the operations were considered experimental.

Soon afterwards, the British Government declared a voluntary moratorium on further transplants because of high failure rates linked to organ rejection and infection.

There were also strong moral objections to removing a heart that was still beating (which was essential for transplant) even if the patient was brain-dead and on a ventilator. It was 1979 before the Conference of Medical

Royal Colleges equated brain death with the patient’s death.

So, Sir Magdi’s decision to defy the moratorium and perform a heart transplant in September 1973 won him many critics, including colleagues, especially when his patient died within hours.

But Sir Magdi was ambitious for Harefield and for a national transplant programme. A certain Ken Clarke, then health minister, described him as ‘mad’.

During an operation, particularly if it is something new, I become completely automaticSir Magdi

As soon as new anti-rejection drugs became available, and the moratorium lifted, Sir Magdi performed three heart transplants early in 1980. Then, he insisted on removing the donor heart himself, which sometimes involved a flight and always a tense four-hour countdown before the heart had to start beating again.

His first transplant patient in 1980 died within two months, the second within hours; the third, Derrick Morris, lived for a further 25 years. Debates about medical ethics raged.

When Sir Magdi decided to perform a heart transplant for 10-day-old Hollie Roffey in 1984, even Christiaan Barnard said it was a mistake. She died within three weeks.

Sir Magdi recalls discussions long into the night about whether he should operate, ‘niggling doubts’, disquiet over critical media coverage and distress over Hollie’s death. But it had been her only chance.

Asked now about how he coped with the risk and criticism, he is deliberate in defining his priorities.

A mural by Hany Gendy depicting Sir Magdi and the Egyptian international football player Mo Salah in Sharqiya Governorate, north of Cairo, in 2020 (credit: Amr Abdallah)

A mural by Hany Gendy depicting Sir Magdi and the Egyptian international football player Mo Salah in Sharqiya Governorate, north of Cairo, in 2020 (credit: Amr Abdallah)

‘I put all my effort into serving that patient and forget that this is a beautiful child I have known for some time. I do have emotions. But during an operation, particularly if it is something new, I become completely automatic, and put all my energy into getting out of this procedure safely in a committed fashion. Afterwards, I can feel exhausted.’

Being lead surgeon was often lonely, he says, especially when breaking new ground.

‘As Lord Brock used to say, you don’t know whether you will meet a policeman on a bicycle, someone very kind, or a whole army which will descend on you and your patient. You are out there on your own. But you are acting totally, I mean totally, on behalf of patients who really have nowhere to go.

‘When something doesn’t go right, the concentration is entirely on: how can we prevent this happening again? If anything wrong happens, it’s got to be the chief, me, who carries the can.’

Different era

Sir Magdi recognises he was the man for a time when clinical governance was less tight and ethical positions still fluid. Would his pioneering be possible today? Definitely not, he says.

‘We couldn’t have done what we did in the early days to advance the care of human beings, in the current environment, when there is so much governance, regulations. They really would stifle innovation.’

Sir Magdi subscribes to philosopher Karl Popper’s assertion that science progresses by ‘leaps of imagination’, not small steps. He points out that the ancient Egyptian goddess of truth, Maat, was beautiful and elusive. ‘If you came near her, she grew huge wings and flew away. So, you have to keep running after truth.’

To keep pushing those boundaries, his clinical work has always run alongside scientific research. He set up the Harefield Heart Science Centre where today scientists in the Magdi Yacoub Institute explore, among other things, the potential of tissue engineering to grow living heart valves and gene editing to address heart disease. He has also established research centres in Egypt, Mozambique and Qatar.

Surgeons do care, a lot more than people thinkSir Magdi

He acknowledges the possibility that scientific advances may one day make transplantation obsolete.

‘Eventually, there has to be other solutions; when it’s going to happen, I don’t want to speculate. But for the time being, transplantation and heart surgery is a fantastic tool for benefiting humanity. Transplantation has done wonderful things: I see people who were going to die in a week without transplantation and who have survived 35 years of fantastic life, have seen their grandchildren.’

Sharing knowledge

Sir Magdi is now considered one of the world’s most innovative surgeons and Harefield is a world-class heart and lung transplant centre.

Through his charity, Chain of Hope, he has set up cardiac services around the globe, including centres in Egypt (Aswan), Ethiopia and Mozambique. Other major heart centres are being built in Cairo and Kigali (Rwanda).

All these centres are free at the point of entry, like the NHS: he is passionate about addressing health inequalities.

Before building the Aswan Heart Centre, he sparked a near-riot by announcing on Good Morning Egypt his intention to provide free cardiac care to children. Thousands queued to see him, and he had to escape through a hospital roof with a police escort.

But Sir Magdi shrugs off the plaudits. He had to be persuaded to lend his name to projects, swayed only by friends’ assertions that they would receive more funding if they bore his name. He agreed to the biography only to ‘inspire others’ to go into medicine.

I see people who were going to die in a week without transplantation and who have survived 35 yearsSir Magdi

His focus now is on legacy, sharing what he has learnt. When we talk, he has recently returned from Aswan Heart Centre, now a major training centre for doctors across Africa.

‘My dad used to say, “I don’t want to leave you money: I want to leave you education and knowledge”. I owe a whole lot of debt to people. My main function in life now is to pass on all that I have learnt to the next generation.’

He sleeps more than he did. His Radio 4 Desert Island Discs choice of a luxury item was a hammock. But he is still pushing, still seeking challenges. His passion for growing orchids has waned since cloning took the skill out of propagation. He developed a new operation to treat a congenital problem called truncus arteriosus as recently as 2019.

‘I firmly believe I cannot be bored,’ he says. ‘If I’m bored, I’m not doing enough. And if I stop, I will rot.’

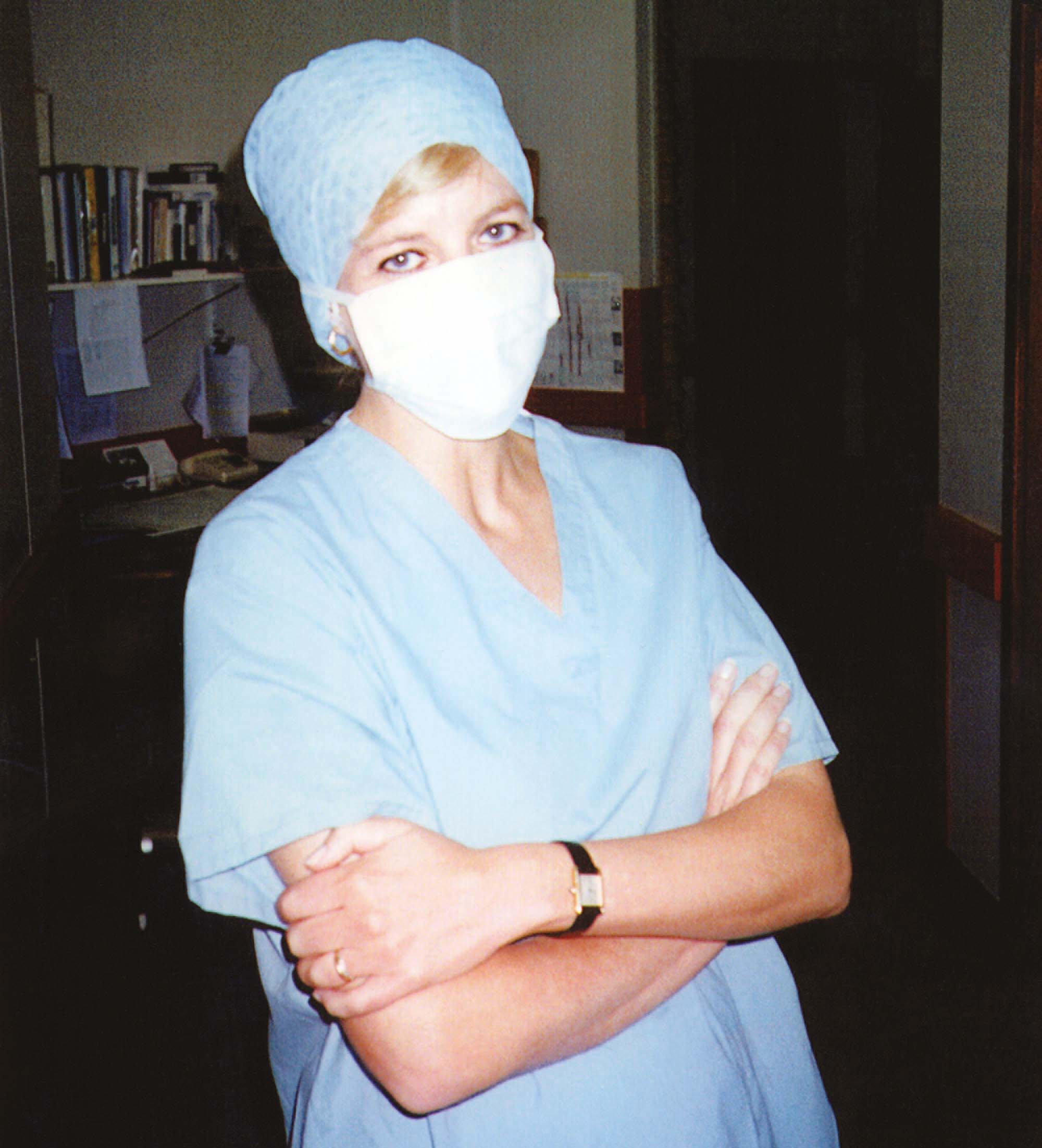

PRINCESS DIANA: Rapport with young patients (credit: Hans Murmann)

PRINCESS DIANA: Rapport with young patients (credit: Hans Murmann)

His friend Diana

As Harefield grew, and its research developed, so did its fundraising. This was often supported by former heart-surgery patients, including comedian Eric Morecambe. It’s a measure of the man that Sir Magdi still has longstanding friendships with many of them.

Another fundraiser and regular visitor to Harefield was Princess Diana, who had become romantically involved with Sir Magdi’s senior registrar, Hasnat Khan.

The princess started making unscheduled visits to patients on Harefield’s paediatric ward. Sir Magdi recalls hearing her laughter, often late at night. Later, she became involved in fundraising and was guest of honour at a dinner at Harrods, then owned by Mohamed Al-Fayed, in 1996.

But when she attended two of Sir Magdi’s operations and a photo emerged of her in theatre, wearing make-up and earrings, the press pounced. They accused her of posing an infection risk – and courting publicity.

Sir Magdi is adamant it was a genuine love of children that drew her to Harefield. ‘She had a rapport with children that I had rarely witnessed in others.’

They became friends. It was Princess Diana who drove him to Heathrow when his brother Jimmy died after a fall in the Black Forest. ‘Diana was a great comfort to me. I still hear her voice in my head urging me to carry on.’

A Surgeon and a Maverick: the Life and Pioneering Work of Magdi Yacoub is published by the American University in Cairo Press