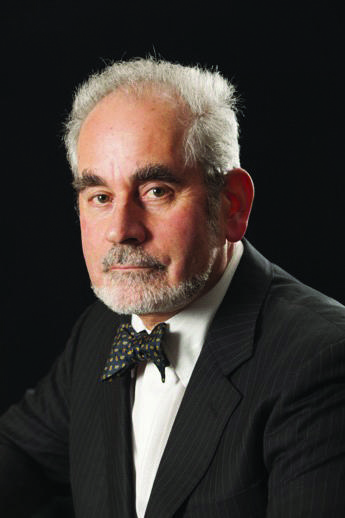

POONI: ‘The most distressing thing is the relatives who were unable to visit’

POONI: ‘The most distressing thing is the relatives who were unable to visit’

‘I put myself into that position and I just wonder how they coped.’ After months of seemingly endless working hours, exhausting night shifts, energy-sapping protective equipment and fundamental reorganisations in care and services, Jagtar Pooni is still thinking of others.

Asked to reflect on how he, colleagues and services coped with the first brutal wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr Pooni, an intensive care consultant in the West Midlands, immediately thinks of the patients and their families.

Dr Pooni says: ‘It [working in this crisis] has heightened everything. Even as I speak to you now I can picture certain patients who have got better and other patients who have not and I am getting emotional and upset now reflecting on this time.

‘The most distressing thing is the relatives who were unable to visit – these poor people could not visit their loved ones in hospital, and many of them died in the following days and weeks without family present. I can’t imagine what they must have been going through in this situation.’

Stress and isolation

For many of these patients these were not short periods of time alone, accompanied only by the doctors and nurses trying to stretch their care and compassion across as many people as possible in a profession used to giving much more one-to-one focus. Many occupied intensive care beds, supported by mechanical ventilators, for 50 days or more.

Dr Pooni, who has isolated himself from family and feared for his, and their, safety every day, adds: ‘It was a personal inconvenience and difficulty for us, but in no magnitude does it compare to the families and relatives waiting at home. When I reflect on things, I push aside the challenges and the everyday stress and the final conclusion is this is the most distressing thing I have witnessed.’

It says an awful lot for Dr Pooni and the profession that his thinking is so fundamentally selfless – but now the worst of the first surge of demand has passed it will also be important to focus on the profession.

The weeks and months since the pandemic arrived in the UK have been relentless and brutal for doctors working in intensive care. For the future of the service, its workforce and patients – particularly in the uncertainty of this new disease and any potential further peaks – this remarkable time is a period from which lessons must be learned, and quickly.

Staff were stressed and crying and upset because of the large workloadDr Pooni

BION: ‘There will be consequences from the pandemic’

BION: ‘There will be consequences from the pandemic’

The first issue at hand is that staff are not only exhausted but may be grieving and feel bereaved having withstood a wave of additional trauma during the crisis.

Dr Pooni says: ‘You could and can see the effect on staff, you could witness it.

The situation here was the staff were stressed and crying and upset because of the large workload and the processes that we had – although we were doing the best we could – that in the system we were not providing the best care for patients and patients’ relatives.’

It is an issue Julian Bion, professor of intensive care medicine at Birmingham University, is seeking to address.

Professor Bion explains: ‘Sitting down and talking to a family in person, being able to put your arm around somebody, feels better – less bad – than trying to communicate over the phone and saying we can’t get your father or son better and that they are going to die. Doing that over the phone is extremely hard. To do it on such scale here is a different matter entirely. You end up with bereavement on both sides. There may be – I think there will be – consequences from the pandemic in terms of anxiety, depression, burnout, and staff sickness.’

Disrupted lives

GLOVER: ‘There is an issue in terms of people not having taken the opportunity to recuperate’

GLOVER: ‘There is an issue in terms of people not having taken the opportunity to recuperate’

For Paul Glover, intensive care consultant in Northern Ireland, the toll has been obvious – with difficulties having pervaded every area of life for staff on the front line.

‘Our routines are different, the structures of our weeks have been changed, there has been disruption to work lives and home lives with children not at school, partners having to work from home and all sorts of other issues. It is all contributing to the pressures people are feeling. I think there is an issue in terms of people not having had or having taken the opportunity to recuperate following the first phase.’

When there is a death you want to be able to come out of that with a capacity to move forwardProfessor Bion

Professor Bion is keen to use reflective learning to help staff cope with what they have been through. For the last three years he has been developing a reflective-learning programme and toolkit and he has applied for National Institute for Health Research funding to test whether this can improve resilience and recovery for staff, and care for patients across the health service.

The toolkit provides staff with multiple methods for learning from their experiences – and focuses on learning when things go wrong as well as when they go right, a ‘key part of learning’.

Professor Bion says: ‘When there is a death or something goes wrong you want to be able to come out of that with a capacity to move forward, to create a better future. That is what reflective learning does when done well and that is a key part of mitigation.’

The exhaustion of doctors after this relentless period on the front line is a significant problem, too, though – particularly with potential future waves of COVID-19 looming and the spectre of a possible rise in demand related to patients staying away from healthcare, or being unable to access it, during the pandemic.

Listen to staff

WALSH: ‘Staffing needs to be at the centre of everything’

WALSH: ‘Staffing needs to be at the centre of everything’

BMA consultants committee deputy chair Simon Walsh says: ‘What I’ve been seeing and hearing from my colleagues around the country and where I work in London is just all about exhaustion.

‘When the pandemic first hit the UK doctors and all other healthcare workers did their absolute utmost to keep services going while dealing with lots of critically ill patients with COVID-19 and have been exposed to quite an unknown level of risk as well, particularly in the early weeks with all the questions around PPE – that combination of massive workload and very large numbers of very unwell patients but also that sort of stress of the unknown risk to your colleagues, yourself and your families at the end of the day.

‘The most important thing that trusts can and must do is listen to their staff and the groups that represent them because there are lots of things that will be different locally that are concerning doctors and other healthcare workers. One of the things that will be a common theme will be having flexibility in carrying over annual leave and having a reasonable discussion about how doctors who have done excessive amounts of shop-floor, hands-on, clinical work are given time to do their SPA work for reappraisal and revalidation.

‘We also need to be mindful doctors have given their utmost to the point of harming their own health – physically and mentally. They need to be given flexibility in terms of leave and to have flexible working patterns going forward.’

Dr Glover adds: ‘Sustainability is a massive issue. What is quite clear is that the effort that was put in is not sustainable and it can only be delivered for short periods of time and to do that it is imperative that processes are put in place to allow staff to recover.’

There may be few genuine positives to take from the pandemic but if little else the importance of intensive care – well resourced, properly staffed and genuinely valued – must surely be the defining conclusion.

Second wave

Intensive care doctors told The Doctor they believe the Government has made funding available for expansion of departments potentially equating to 150 per cent of current capacity in certain areas – but the Department of Health ignored several requests for clarification on this – and there are reports that capacity in London is to be increased more permanently, in case of future waves of illness.

But what is the importance of increased capacity?

Professor Bion says the NHS is usually running too close to, or rather above, capacity – while recognising that intensive care capacity in this country has increased in recent years.

‘It’s true the UK has always had fewer resources for intensive care specifically than comparable developed affluent countries such as the USA, Switzerland, Germany and France. But there has been a major increase in intensive care resources during the last 10 years; they have tended to be concentrated in the larger centres which probably makes sense.

‘It copes reasonably well – but it’s tight as the whole of the health service is. The health service tends to run at 90 per cent occupancy most of the time but that is measured at midnight and doesn’t reflect what it feels like during the day – it is usually more like 120 per cent. There is always pressure on scarce resource.’

Many doctors believe more capacity is needed to allow flexibility and respite from demand.

The most important thing that trusts can do is listen to their staffDr Walsh

Dr Glover says: ‘The pandemic has highlighted the importance of critical care in a functioning healthcare system and it is a service that frequently runs at 90 per cent capacity. When you run at that level of capacity it’s insufficient to sometimes meet demands in normal times let alone when a pandemic takes things into a different area altogether.

‘A fire extinguisher is still very useful when you don’t have to use it – that’s the comparison. We need to accept we need to have spare capacity in critical care to meet peak demands.’

However, the argument isn’t just about beds and ventilators. Staffing is crucial.

Dr Walsh says: ‘It is a really complex area – there has been a lot of redeployment of staff to help us get through the first peak of it but going forward trusts are trying to re-establish elective work and normal business because we need to find a way to continue that important work. It means rapid reconfiguration plans are being made and instigated in trusts. My worry is that in a lot of these discussions staffing is the appendix at the end, but really that needs to be at the centre of everything. Trusts may need staff to move site, move area, take on new ways of working and coming out of this excessively stressful time staff need to be at the centre of this conversation.’

Preventive measures

BANERJEE: ‘To focus solely on increasing ventilator capacity has been wrong’

BANERJEE: ‘To focus solely on increasing ventilator capacity has been wrong’

Some doctors would argue that the best way to respect and value the sacrifices made by intensive care doctors and to protect their future is to focus not purely on ventilators and bed numbers but to have a properly coordinated effort to stop the spread of the disease before people end up in intensive care with, ultimately, quite high fatality rates.

Ami Banerjee, associate professor in clinical data science at University College London and academic cardiologist, says: ‘I think the whole debate has been framed wrongly. We’ve been from the beginning talking about ITU or ventilator capacity only. My own research has shown that we could have and should have focused our efforts on early suppression and early lockdown. To focus solely on increasing ventilator capacity when not focusing on the upstream bit has been totally wrong in my view. We were forced to scramble to find extra capacity when we had actually seen in other countries in Europe what happens if you don’t manage the infection rate.’

The UK has always had fewer resources for intensive care than comparable countriesProfessor Bion

Dr Banerjee – who urged the Government and national health leaders to place clinical academics at the heart of its future planning in continuing to tackle this pandemic – adds: ‘We’ve proven that with a lot of strain we coped – every facility around the country has been coping but it came at a cost and it was an unnecessary strain created by lack of forward planning. Evidence based policy is a word thrown around with reckless abandon but there was a massive lack of that here.’

It’s certainly not all about capacity. And there may be some much bigger questions to answer: Can hospitals continue to be structured as they are in the COVID-19 world with facilities stretched trying to provide safe spaces for people with and without the virus? Should the whole hospital estate be reconfigured?

As Dr Pooni says: ‘Imagine a situation on a critical care unit where you have COVID patients but you now have patients who don’t have COVID but have other critical illnesses and are at risk of developing COVID. We try to cohort patients, isolate patients, put them inside rooms and section off critical care units physically, but it is difficult and ultimately decreases our capacity as there are beds and spaces we can’t use. There are great challenges as to how we do this and where we look after these patients.’

Sharing resources

These are huge questions which will need serious care and attention. In the meantime, what can be done?

The Doctor understands a group of leading intensive care professionals are in negotiations to extend specialist intensive care transfer systems, operated in some patches of the country which see patients or specialists moved between hospital sites, extended across the country.

This could be crucial. Professor Bion says: ‘We haven’t had satisfactory transport systems to share resources between centres and the coronavirus has further highlighted the need for a transport system which we have been saying since I was a junior doctor.’

Ultimately, giving this remarkable group of doctors the working environment they need, and the time away from it that they need, will require serious discussions, investment and change.

But while those discussions will be required, for intensive care specialists such as Dr Pooni the focus will always be on care – and he, and colleagues, will do their best to be ready for whatever comes next.

‘We have learned from everything that has happened. We have learned and processed, we have the care pathways, the new staffing structures, the hospital organisation and the non-ITU staff trained and people aware of the risks. We have so much in place that if a surge comes tomorrow, we could cope with it.

‘But that’s the non-emotional side. Staff on the critical care unit are exhausted. Having learned from all those experiences they would be able to deal with the situation, but they are exhausted and they need to rest.’

Wellbeing resources during COVID-19

Some of the external sources of support the BMA suggests for doctors include:

- HealthSHIP – Medical student volunteers offer to help NHS key workers with non-clinical services such as childcare and groceries

- NHS Staff support line – Confidential staff support line, operated by the Samaritans, for when you’ve had a tough day, are feeling worried or overwhelmed, or maybe you have a lot on your mind and need to talk it through

- Frontline 19: free online wellbeing support – Mental health and emotional wellbeing support service set up by therapists to support frontline staff