‘The pressures on the whole hospital are huge,’ says specialty trainee 4 registrar Kerrie Thackray (pictured) when asked to compare her working conditions with before she took a seven-year career break to raise her children.

Now working in Hertfordshire, she explains: ‘There are constantly winter pressures now.’

Demands on health services, both in the emergency department and at GP surgeries are ‘massively up’, she says. ‘Everyone’s very, very tired. Everyone’s worked incredibly hard in very trying circumstances in the last few years – and there hasn’t been a lighter summer as there used to be traditionally. It’s just been constant.’

One thing that hasn’t been constant, in real terms, is junior doctors’ pay – which has eroded by a quarter since 2008 – five years after Dr Thackray graduated.

Financially speaking, she says: ‘Things are a bit more difficult now. I made a decision to have five children, and children involve lots of costs, but everybody across the hospital is struggling with the cost of living crisis. Costs have gone up massively, we don’t need to persuade anyone of that, but there’s a real disconnect in the understanding of what we get paid and should get paid.’

Benefits diminished

For context, she adds: ‘Perhaps junior doctors used to get paid well, but we’ve lost some of the benefits we had when I first graduated, such as free accommodation in the first year, which made things easier – especially if you’re moving round the country [on rotation].

‘I was able to buy a flat during my first job. Most foundation year 1s I work with now would really struggle with that. When I did my degree, tuition fees were about £1,000 a year. Medical students now graduate with tens of thousands of pounds of debt. Now, student-loan interest rates are much higher.’

Dr Thackray notes the vocational nature of medicine, and the NHS’s ‘monopoly employer’ status in the UK for doctors before they reach consultant level, has contributed to why junior doctors have not left in droves for the private sector – though notes how a growing number have moved to work overseas.

‘Most of us want to work in the NHS,’ she adds. ‘We believe in the NHS and we are all working really, really hard to protect it. Most of us don’t want to do private work.’

But because goodwill has been stretched while pay has stagnated, she explains: ‘Everyone’s feeling under-appreciated because of the sheer amount of work – and that goes across the whole hospital, doctors, nurses, all the ancillary staff and other health professionals.’

I don’t think the general public realise that’s the level of responsibility some junior doctors haveDr Thackray

Campaign in support of all hospital workers

Campaign in support of all hospital workers

As nurses go on strike this month, she stresses: ‘Every doctor will say that while this [pay] dispute is about us, we’re part of a campaign supporting all of our colleagues in the hospital.’

As a registrar at ST4, BMA calculations show Dr Thackray earns £24.46 an hour. She notes: ‘For that, I have a huge amount of responsibility. I might be one of only two medical registrars in a hospital of more than 1,000 beds, in charge of the cardiac arrest team; the senior decision maker for all the medical admissions and all the medical wards, offering medical advice to all the other specialties in the hospital. That feels like a lot of responsibility for the pay I receive. I don’t think the general public realise that’s the level of responsibility some junior doctors have.’

She acknowledges how some senior grade junior doctors may feel apathetic towards voting in the upcoming ballot, which requires a turnout of 50 per cent of those eligible to vote in order to be considered to have support for industrial action.

‘There’s definitely an element of everyone just being so tired and not having the headspace to do anything extra,’ she explains. ‘But, at the same time, we have to protect the doctors coming through and protect our profession.

‘We want to attract the best and engaged medical students and doctors. We want to protect the NHS and it’s frustrating seeing how that’s being eroded. It’s important for future-proofing the NHS and caring for the future of our profession that we all get involved.

‘If I strike, there’s a real direct financial implication on my family but there’s a financial implication for the more junior doctors as well, who have many more years ahead [on lower pay grades].

‘There are parts of the profession who will say “it was worse when I was a junior doctor, with 100-hour weeks”, but that doesn’t mean this isn’t bad as well.

‘We can’t play top trumps as to who has it worse. We need to take the situation we have now, see that it is bad, see that we’ve got doctors leaving the country, leaving the profession, burnt out on a huge scale, and do what we can to improve the situation as it is now.’

Over the top

While the 2016 junior doctor contract limited the average working week to 48 hours, down from 56, and capped consecutive night shifts at four, Dr Thackray notes how today’s juniors are working beyond their hours almost every day – and tackling ever-more complex patients as medicine evolves and treatments improve.

‘That’s because you have a set of dedicated doctors who are trying to make up for the inadequacies of the system. We shouldn’t have to do that. Junior doctors should be exception reporting that, but the amount of effort involved is just another thing to do.’

Many, including herself, opt to work less than full time for a more manageable work-life balance. But reducing hours means a drop in take-home pay.

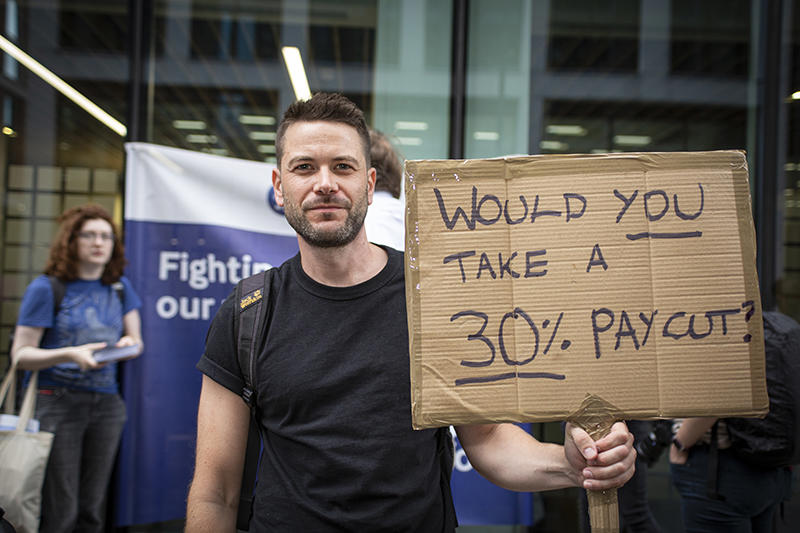

Junior doctors protest pay in London in July 2022

Junior doctors protest pay in London in July 2022

And Dr Thackray notes a ‘real lack of continuity across wards and teams’ since before she returned to medicine when the GMC ‘removed barriers’ to re-entry at the height of the COVID pandemic in 2020.

‘When I was initially a registrar I worked for a block, so for one consultant on one ward and had specific junior doctors I worked with as a team. You had community and support. We’ve lost that continuity that benefitted both us and the patients.

‘It’s been slightly easier for me recently because I’m settled and have a community outside of work, but there are junior doctors scattered around the country who, especially during lockdowns, were not able to meet other people.’

Everyone is feeling incredibly tired and burnt outDr Thackray

This lack of continuity has also impacted training opportunities for younger doctors, she notes, with senior grade doctors ‘sometimes not having any capacity to do anything else on top of absolutely everything else they’re already doing’.

Dr Thackray insists: ‘That’s not a fault of the consultants, that’s just how medicine is working.’

Her opinion, like that of many doctors, is that the systemic issues leading to the NHS workforce crisis can only be fixed with retention, which boils down to better conditions and pay.

‘Everyone is feeling incredibly tired and burnt out – which makes everyone’s threshold for coping with things much lower,’ she says. ‘With COVID and flu and increasing staff sickness, I don’t know how we’re going to cope this winter.’