When Harry Burns decided to leave surgery and move his focus to public health, there were some who couldn’t believe it – not least his colleagues.

As a trainee then consultant surgeon at Glasgow Royal Infirmary, he had worked with a prestigious team that included such luminaries as Sir Andrew Kay, David Hamilton, and Sam Galbraith (later to become Scottish health minister).

He decided to leave this – in medical career terms – gilded existence to do a master’s in global public health.

‘Lots of guys thought I’d gone crazy, bonkers, and asked why I’d do that,’ he reminisces. ‘A lot of folk thought I’d taken leave of my senses. I was never interested, at all, in private practice or anything like that – it just didn’t interest me.

‘I’d been a consultant for five years at that point, and I thought, OK, I know how to do this. What else can I challenge myself with? Do I want to do this for another 30-odd years – let’s go and see what else I can do. I was attracted by the science of public health. I don’t think they think I’m mad now.’

Fighting inequality

Since completing that master’s degree in 1990, Sir Harry has had a varied career, including a stint as director of public health with Scotland’s biggest health board, Greater Glasgow, and as chief medical officer for Scotland – a post he held between 2005 and 2014. He is professor of global public health at the University of Strathclyde, and, this month, he takes up a new role as president of the BMA. This is usually a one-year post, which begins at BMA annual representative meetings, although the timing of this year’s ARM means Sir Harry will have a shorter term than his predecessors, through to the next meeting which is scheduled to take place in June next year.

A lot of folks thought I’d taken leave of my sensesDr Burns

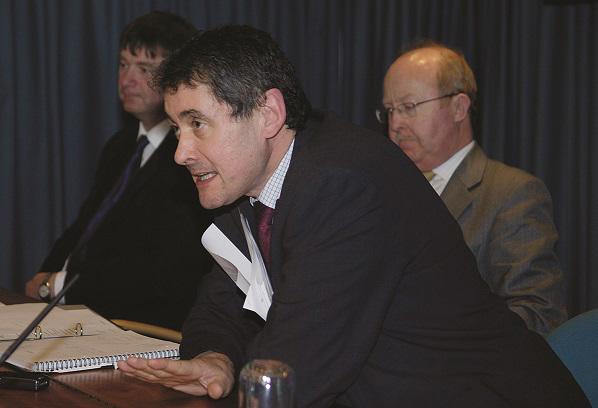

FIRM HAND: Sir Harry in 2006 when he was chief medical officer for Scotland at a meeting about the outbreak of H5N1 bird flu

FIRM HAND: Sir Harry in 2006 when he was chief medical officer for Scotland at a meeting about the outbreak of H5N1 bird flu

All the while – even while he was a consultant surgeon – he has been driven by an interest in the science of wellness, of health inequalities, of the factors that determine whether someone will have a long and healthy life – or a life cut brutally short.

Colleagues – including Sam Galbraith – had suggested that he take up a career in politics, but this is something that never attracted him, he says. Nevertheless, there is something inherently political about health inequalities – so has it been difficult to remain outside the political arena?

‘I have tried all the time to shape my opinions on the science that I see before me,’ he says. ‘The classic thing is that inequality in health is socially determined. Well actually, there’s a biology associated with that, and unless you understand the biology, then you’re never going to come up with the answer to fix it. I keep saying to folk when I talk about this that this isn’t a political view, this is the science of inequality. And unless you can get that across, particularly to those on the right of the political spectrum, who tend to believe that people are struggling because of poor choices they’ve made, unless you can show them that there are actually some biological aspects to why they are where they are, then they’re never going to want to sit down and try to address these problems.

‘I try to stay out of politics, although at the moment, I don’t know why I’ve still got a working television in the house because I keep wanting to throw things at it whenever I see certain politicians on pontificating about coronavirus.’

Political interference

Sir Harry – he was knighted in 2011 – has not been directly involved in the COVID-19 response at either a UK or Scottish Government level, although the latter has asked him to chair a group to look at emergency planning with a particular focus on winter.

Does he wish he was still there, standing next to the first minister as she gives her briefings?

‘No,’ he says very definitely. ‘Been there, done that. It’s someone else’s turn. Gregor [Smith, interim CMO for Scotland] is doing a great job. You move on. They’ve asked me to do a specific thing and I’ll happily help them out, but I want to have what they’ve asked me to do done and dusted quite quickly so that I can get on with doing other things.’

I don’t know why I’ve still got a working TV in the house because I keep wanting to throw things at it whenever I see politicians pontificating about coronavirusDr Burns

Given that he wants to ‘throw things at the television’ when watching UK COVID-19 briefings, what would he want to see done differently? He speaks carefully: ‘If England had done what Scotland has done…’ he says with evident regret. ‘Eventually, Scotland imposed lockdown and I think that was out of a sense of, um, frustration over what was happening – or the fact that nothing much was happening. It was very, very clear that England was much more interested in just letting it ride because they didn’t want to disturb the economy, and eventually – I think – the Scottish Government just said “we’re shutting schools; we’re shutting down”, and England just went immediately after that.

‘If you remember, the chief scientific adviser, [Sir Patrick Vallance] when asked about Liverpool versus Atletico Madrid football match came away with something about there being no evidence that having a mass gathering like this, or having a crowd at a football match would increase the risk of getting this virus. I thought “Really? Does he really believe that?” and you know, technically speaking he was correct because no one had ever done a randomised controlled trial of football matches versus no football matches, but you put 50,000 football fans [there], and you don’t see that all the singing and dancing and jumping up and down is going to spread a virus? No. It was pretty clear there was a lot of political interference there.’

Sir Patrick said in response to a question from Boris Johnson at a briefing that there was a very low risk of infecting a large number of people at a stadium, and that most transmission tended to take place with friends and colleagues in close environments ‘not the big environments’.

A spokesperson for SAGE, which Sir Patrick chairs, says: ‘At no time has SAGE advised on specific sporting events. The role of SAGE is to provide government with science advice. It is for ministers rather than SAGE to make policy and operational decisions.’

As an internationally known leader in public health, constantly invited to talk at conferences and to share his perspectives via the media, does Sir Harry feel a weight of responsibility?

He thinks carefully before responding: ‘I don’t say things unless I believe them to be true and I don’t believe them to be true unless I’ve seen some evidence that they’re true. I don’t express an opinion without having some scientific reasoning behind it – which again is another reason why I’d never be a politician, because they express opinions because they’ve got opinions, and I like to have evidence.’

Public health wins

CHEERS: Sir Harry with Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon

CHEERS: Sir Harry with Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon

Even though Scotland has a far lower prevalence of the virus, he does not think that is a reason for closing the border – yet. ‘If you get a sporadic outbreak, yes I’m in favour of local lockdowns, but if England started to have a second peak, if the whole of England started going up and up and it wasn’t happening in Scotland, that might well be a reason for restricting movement. But we’re still going to need to have food deliveries, we’re still going to need to survive, and we’d need to make sure there would be a way of making these happen safely.

‘So, there would be an alternative to just mindlessly closing the border in those circumstances.’

In his time as CMO for Scotland, there were some major public health initiatives, including legislation to ban smoking in public places, and to oblige minimum unit pricing for alcohol. Asked what he is most pleased with, however, his answer is a little unexpected.

‘I think the most interesting stuff that I was involved with was the improvement stuff – the patient safety programme, the Early Years Collaborative [a multi-agency improvement programme designed to ensure that children get the best start in life and that families are supported] and so on.’

My medical colleagues have covered themselves in glory over the past few monthsDr Burns

He has, he says, as the son of a physicist, always been interested in systems and how things work. ‘Systems thinking, systems change – looking at the delivery of healthcare in a different way, and recognising that the way to change things, the way to improve things, is not shouting at people, but getting people to work differently: giving them permission to determine what makes the outcome better,’ he enthuses.

‘Get them to suggest how you improve systems, get them to test it, then once they have tested it, and seen that it works, then you put it into practice. It’s that sort of thing that I get really very exercised about and interested in.’

He was, he stresses, ‘absolutely’ pushing for the public health legislation on smoking and alcohol, but that’s not the end of the story.

‘These are steps in the process. But it’s about giving people control. It’s not telling people that it’s bad to drink and it’s bad to smoke and we’ll make it really difficult for you to smoke and all that sort of stuff. It’s about gradually showing people that they can make small changes in their lives that will add up to a big change in their wellbeing. It’s a different kind of approach that you need.’

So is he looking forward to taking the BMA presidency? ‘Well I’ve just got on to the email system and there are a hell of a lot of emails flying around,’ he laughs.

‘It’s a great honour to be asked. My medical colleagues have covered themselves in glory over the past few months and health workers in general have shown themselves to be quite heroic in the way in which they’ve exposed themselves to great risk, and as we know, many of them have succumbed to the virus. So, it’s an honour to be asked to do this and I’ll do it to the best of my ability, to support them and to help the medical profession support the population at large.’

Listen to Sir Harry Burns in conversation with the current BMA president, Raanan Gillon