Here we all sit, in this tiny room with its pseudo-comfortable chairs and bare walls.

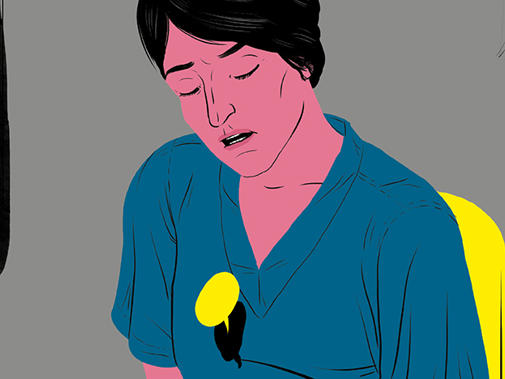

Me, in dishevelled scrubs with a pen in my hair, looking too young to be telling you this kind of news. And you, woken in the small hours with words that hide their real meaning like matryoshka dolls. ‘Get here as soon as you can.’

I will stick to the facts, to the bare bones, excuse my pun. I will use numbers, move sequentially. Pause for effect, to let it sink in. I will look you in the eyes when I speak because it is my actions, my team’s actions, that I have to tell you about, to take ownership of.

I do not think for one second you are listening to me or understanding because how can you, how can you absorb these words when all that is running through your head is white noise and blankness.

You are remembering, perhaps, the time your mother held you after someone broke your heart. How she stroked your hair, promised there would be someone better and then handed you tea in your favourite mug. You are thinking about the rings she was wearing when she came into hospital.

The last time you went out for dinner together. Who her favourite couple was on Strictly Come Dancing.

Or maybe it is your brother who is in your head – the one who stole food off your plate when he didn’t think you would notice, who snuck you into a gig when you were underage, who shuffled his feet with a choked-up throat when you left for university but would never tell you he misses you, never say out loud that he loves you.

I do not know any of this. What I know of them, my patient, is how difficult it was to find a vein to put the cannula into, how three people were trying on both arms, blindly stabbing around. How their eyes were open when I ran to their bedside, with a nurse already doing CPR. I know that we tried, we kept trying, to undo what their body had done, to restart, re-shock, reboot.

I tell you I am sorry. I am so sorry. I wish we had run up the stairs faster. I wish we could have fixed it, I wish this was the way it is on TV. I wish we could have predicted this. I feel sorrow for the fact that we failed to prevent the inevitable but also failed to prepare you, we failed to tell you that this could happen because we didn’t know that it would.

This word that I use is inadequate and they all are.

I have nothing to say to tell you how I feel for you. Please look at me and believe that I mean it, but that this word is all I have to give you. Please understand that I would like to hold you and let you cry on me so that you might know that I am more than sorry, this word that is a spectrum, but that you don’t know me and I don’t know you and etiquette dictates that I stay where I am.

I will not cry in front of you but please know that when I tell you these words, my heart breaks too.

That I have to take deep breaths before saying what I know will shatter yours. When I tell you I am sorry, please know that I know and sorrow for what has happened and what is to come for you – the days of waiting, the bureaucracy and the emptiness.

This conversation gets more practised and more fluent but is never easier to have. I haven’t enough experience with language to find more eloquent, meaningful things to say and express to you what I feel. Just know that I do. I am sorry, so sorry.

Revati Naran is an ST3 in respiratory medicine in London